Title: Causal attributions of success and failure made by Grade 10-12 Physical Science learners

Dr Shreen Gutta – shreen.gutta@gmail.com

Faculty of Education – North West University

Co-author: Dr Noorullah Shaikhnag – Noorullah.Shaikhnag@nwu.ac.za

Id orcid.org/ 0000-0002 1423 7696

Senior lecturer –Deputy Director, North West University, Faculty of Education- Mahikeng campus

B Com (UDW-UKZN), BEd, MED, PhD (Educational Psychology, NWU).

Co-author: Prof Anna-Marie Pelser ampelser@hotmail.com

iD orcid.org/0000-0001-8401-3893

Research Professor, North-West University, Faculty of Economic and Financial Sciences- Entity Director –GIFT, Mahikeng Campus.

HED (Home Economics, PU for CHE), B Com (UNISA), B Com Hons (PU for CHE),

M Com (Industrial Psychology, NWU), PhD (Education Management, NWU)

Co-author: Dr Shanae Naidoo – Shantha.Naidoo@nwu.ac.za

ID ORCID:https://orcid.org/0000-0001-8107-6493

North-West University, South Africa: Potchefstroom, North West, ZA

Lecturer: Life Orientation, Sub Area Leader: Edu-HRight (Bio-Psychosocial Perspectives)

MED (Learner Support), PhD (Educational Leadership and Management, UJ).

Corresponding author: Prof A.M.F. Pelser – ampelser@hotmail.com

Ensovoort, volume 42 (2021), number 6: 4

Abstract

People provide explanations to describe why they behave in certain ways or why they succeeded or fail.This phenomenon is referred to as “attribution”. The purpose of attributions is to change a person’s behav-iour and to improve the outcomes. People are more likely to make attributions when events have unexpected outcomes and if the event has personal consequences which will lead to attributional processes andthe individual will seek reasons for the outcome. Attribution Theories investigates how people interpretevents and how this aff ects their thinking and behaviour. In this study, the framework of attribution theoryis utilised to understand what do learners in physical science attribute to their performance. Physical Sci-ence was selected since it is a subject that is known to be problematic to our learners at the FET phase. Thekey objective of the study was to investigate the causal attributions of success and failure made by Grades10-12 science learners and how these types of attributions aff ect the science achievement of learners. Thefour attributional factors investigated were: ability, eff ort (internal attributions), task diffi culty and luck (ex-ternal attributions). A mixed-methods design was employed for data collection with SPSS for analysis. Thetarget population included high schools in two regions within the North-West Province of South Africa(n=60) and the sample s=30. The results were structured through four attribution factors and in terms oflevels of attributions. The four levels are categorized on a continuum from ‘no’, ‘little’, ‘more’ to ‘high’ levelsof each factor of attribution. The factors of attribution are as follows: ability, and eff ort (internal attribu-tional style), task diffi culty and luck, (external style of attribution). Findings indicate that most of the sciencelearners made the highest attribution to ‘more ability’ (43%), and ‘more eff ort’ (46%). The attribution factorsability and eff ort constitute an internal attribution style therefore, most science learners made high internalattributions. In addition, the fi gure indicates that the science learners used fewer external attributions bymaking less task diffi culty (54%) and less luck (42%) attributions. It is recommended that learners becomeaware of types of attributions (ability, eff ort, task diffi culty, luck) that aff ect the achievement of learners inscience subjects in Grades 10 to 12. An internal attributional style results in higher achievement. Therefore,it is recommended that learners be encouraged to adopt an internal attributional style by stressing abilityand eff ort attributions. Science educators need to emphasize eff ort attributions, as eff ort enhances learn-ers’ academic achievement. Eff ort attribution is more adaptive and leads to better expectations of the fu-ture performance of the learner. Causes such as eff ort can be changed, whereas other causes such as luckand ability cannot be changed intentionally.

Keywords: Science Education, Attribution theory, Physical Science performance, FET learners.

1. Introduction

Attributions are the explanations that people give to describe why they behaved in a certain way or whythey succeeded or failed (Graham & Chen, 2020). The purpose of attributions is to change a person’s behav-iour and to improve the outcomes.

People are more likely to make attributions when events have unexpected outcomes, and if the event haspersonal consequences which will lead to attributional processes, then the individual will seek reasons forthe outcome (Cook & Artino, 2016).). Attribution Theories investigates how people interpret events andhow this aff ects their thinking and behaviour (McClure, Meyer, Garisch, Fischer, Weir & Walkey, 2010; Hawi,2010, Hewett et al., 2017). Attributions are made to predict the future and to exert some control overevents. The key objective of the present study was to investigate the causal attributions of success and fail-ure made by Grades 10-12 science learners and how these types of attributions aff ect the science achieve-ment of learners. The four attributional factors investigated were: ability, eff ort (internal attributions), taskdiffi culty and luck (external attributions).

People are more likely to make attributions when events have unexpected outcomes, and if the event has personal consequences which will lead to attributional processes, then the individual will seek reasons forthe outcome (Cook & Artino, 2016).). Attribution Theories investigates how people interpret events andhow this aff ects their thinking and behaviour (McClure, Meyer, Garisch, Fischer, Weir & Walkey, 2010; Hawi,2010, Hewett et al., 2017). Attributions are made to predict the future and to exert some control overevents. The key objective of the present study was to investigate the causal attributions of success and failure made by Grades 10-12 science learners and how these types of attributions affect the science achievement of learners. The four attributional factors investigated were: ability, eff ort (internal attributions), task difficulty and luck (external attributions).

2. Theoretical framework

There are several theoretical models of Attribution Theory. Heider (1958) is seen as the originator of the Attribution Theory. He noted that there are three determinants of achievement: Ability, effort and task difficulty. He regards ability and effort as internal factors, whereas task difficulty is seen as an external causal factor affecting the outcome. Heider (1958) and Rotter (1966) were concerned with the perceived causes of success and failure and their locus of causation. Heider’s studies were beneficial to understand how one may predict and modify future behaviour.

Kelley (1967) identifies cognitive factors that are considered when people make internal or external attributions. According to Kelley (1967), people make attributions by using the co-variation principle. Three kinds of co-variation information are Consensus, distinctiveness and consistency.

Consistency refers to whether or not an actor’s behaviour in a situation is the same over time: distinctiveness refers to whether or not a person’s behaviour is unique to the specific situation: consensus refers to whether or not other people in the same situation tend to respond like the actor. Highly consistent behaviour is likely to result in external attributions when distinctiveness and consensus are high and internal attributions are most likely when distinctiveness and consensus are low. For example, student A’s outcome in an examination is persistent over time (high consistency), not unique to the other class members (low distinctiveness), and unlike the outcome of his classmates (low consensus). The teacher would be more likely to make an internal attribution and conclude that student A’s failure is due to his personal disposition (Soriano-Ferrer & Alonso-Blanco, 2019).

Bernard Weiner’s Attributional Model: Weiner (2010) created the framework that is used today in respect of academic achievement. Weiner stressed the relationship between a person’s causal attributions for success and failure and academic achievement. The most prevalent factors that people use to justify their successes or failures are ability, effort, task difficulty and luck (Mudhovozi, Gumani, Maunganidze & Sodi, 2010; Fishman & Husman, 2017). The causes, ability and effort are considered as internal factors since they originate within the person, while task difficulty and luck are seen as external causatives, as they originate outside the person (Weiner, 2010; Igbaakaa, 2019).

These perceived causes are classified into three causal dimensions: stability shows how stable the perceived cause is, locus investigates whether the cause is internal or external and controllability examines whether or not the perceived cause can be controlled (Basturk & Yavuz, 2010:1940).

Ability is stable and an internal factor over which the learner does not have much control. Task difficulty is stable, external and beyond the learner’s control. The effort is unstable, internal and the learner has control over this factor. Luck is unstable, external and the learner has almost no control over the chances of manifestation (Batool, Muhammad, & Qaisara, 2012; Basturk & Yavuz, 2010).

The locus and stability of causal attribution determine the expectancy of future success. When a student attributes his/her failure to a stable factor such as subject difficulty (external, stable and uncontrollable), he/she is likely to expect future failure. If failure is due to a lack of ability (internal, stable cause) or an unfair teacher, then future failure can be anticipated. However, if failure is perceived as due to an unstable factor (bad luck or insufficient effort exerted on the task), failure will not be anticipated. Locus and controllability, on the other hand, relate to affective states or the emotional value of outcomes. Locus influences feelings of pride and self-esteem, and controllability jointly influences feelings of guilt or shame with the locus of causality. Thus, locus and control determine whether guilt or shame is experienced following failure; and these are independent dimensions.

These attributional causes play a major role in moulding future expectancies and students’ motivation to learn (Basturk & Yavuz, 2010). Students’ beliefs about their causes for success and failure greatly influence their academic achievement. There is a relationship between attributional patterns and achievement in school. Nenty (2010) noted that an internal attributional style leads to better achievement, whereas, external attributions are related to negative achievement.

Internal attributions ascribe the causes of behaviour to personal dispositions, traits abilities and feelings. External attributions ascribe the cause of behaviour to situational demands and environmental constraints. Internal and external attributions have a tremendous effect on one’s everyday interpersonal interactions (Weiner, 2010). These attribution patterns influence the learner’s self-concept, expectancies for future situations and motivation. Learners are strongly motivated by the pleasant outcome of feeling good about themselves. The amount of effort the student exerts on a given task is determined by the person’s attributions for their success or failure.

Weiner’s Attribution Theory explains why students react in certain ways based on their achievement and expectations. He notes that people ascribe their own success or failure to future expectations of success, emotional reactions and selfesteem (Batool et al., 2012). Learners could benefit from the ability to reason about the causal relationship for their successes or failures and such ability helps them to predict the outcomes of their actions (Cook & Artino, 2016).

Attribution researchers have found that people often make misjudgements when evaluating the behaviour of others and tend to attribute the other’s behaviour to their inner dispositions which are unchangeable and uncontrollable. Hence, these people believe that they have control over their lives (Mudhovozi et al., 2010). This tendency is known as the fundamental attribution error where people are inclined to over-estimate the role of internal causes (person’s traits or attitudes) and underestimate the role of external factors in explaining other people’s behaviour. It is the tendency to attribute a student’s failures to a lack of personal characteristics e.g. low aptitude (internal) rather than to situational causes. Another student’s success is explained in terms of an easy test (external) rather than internal causes. A student’s own failure is rationalized in terms of external causes such as task difficulty or bad luck (Mudhovozi et al., 2010). Success is attributed to internal factors: ability (internal, stable, and uncontrollable) and effort (internal, unstable, and controllable).

Consistent with many previous studies on attributions and achievement, students show self-serving attributional patterns of attributing their highest marks to internal causes (effort, ability) more than their lowest marks, and attributing their lowest marks to task difficulty more than their high marks. However, counterto self-serving bias, they invoke luck for their best marks rather than their worst marks (McClure et al., 2010). By claiming credit for success, the claim gives the student a sense of control over what happens in their lives and in other people’s lives. In-group members’ attribution of failure to the situation is a common tendency engaged to protect the student’s self-esteem, and not feeling demoralised when they fail. This bias is universal across all cultures, genders and age groups (McClure et al., 2010; Mudhovozi et al., 2010).

Manzoor & Mahmood (2019) found that high achievers attributed their success and failure outcomes more to effort and ability. Low achievers, on the other hand, attributed their low marks and weak performance to luck and task difficulty. The results in Manzoor and Mahmood’s study were consistent with Weiner’s theory that high achievers associated their outcomes with internal factors. Low achievers associated their outcome with external factors (luck and task difficulty).

McClure et al., (2010) contend that grade 11 students who attributed their success to internal factors (effort and ability) attained higher marks. In contrast, students who attributed their success to luck, family, and friends gained lower scores. This finding is consistent with Weiner’s (2010) theory that external attributions for success lead to poorer achievement.

The results of McClure’s study also showed that failure attributions to lack of effort and to the teacher lead to the attainment of higher scores. On the other hand, attributing failures to family and friends lead to lower marks. Attributing failures to the teacher is consistent with the self-serving bias where people attribute success to internal causes and failure to external causes as such attribution enhances the self-esteemof the student.

Attributional theories contend that effort attributions (controllable) increase perseverance and that it is the strongest predictor of achievement (Weiner, 2000; Batool et al., 2012). They further claim that ability attributions for success and failure predicted achievement better than effort attributions. Attributing success to ability leads to pride, self-efficacy and persistence. Other studies also suggest that ability attributions for success have been related to higher academic achievement (Frijters et al., 2018; Cuevas et al., 2014).

If success is attributed to an internal and controllable cause the student feels proud and increased self-esteem. The increased expectation of high future outcomes is associated with positive emotional reactions and determines the subsequent outcomes, that is, behaviour depends on thoughts as well as feelings. Failure and lack of ability (internal, uncontrollable) evoke feelings of shame, embarrassment and humiliation (Weiner, 2000). When learners’ failure is attributed to internal factors, self-esteem can be diminished. In classroom settings, students need a sense of positive self-esteem and competence and they need to be reassured; otherwise, they give up and say that the task is too difficult (Rusillo & Arias, 2004:101; Nathaniel, 2019). If teachers set very difficult tasks, expanded effort on the part of the students will not be relevant.

When students realize that success is controlled by task difficulty the students aim to control such success.

When teachers praise students for success with little effort, such acknowledgement teaches learners not to work hard. If a teacher criticises learners for failure that could have been achieved with effort, such admonition communicates to students that they have the ability to succeed and they should put in the requisite effort (Batool et al., 2012).

Other studies (Chen et al., 2016; Fwu et al., 2018) have shown that when students attribute their failure in the test to lack of effort rather than blaming it on external influences, they are more likely to perform better in future tests. When students make stable attributions and believe that they succeeded because of the effort that they put in, then they will put in more effort into the task at hand in order to succeed, and if they believe it was due to ability, they will then expend more effort on the task in order to succeed. Students will not be interested if they believe that their success or failure is due to external factors. Teachers must encourage students to believe that they have the ability (stable) and that they can control effort. Thus, ability combined with effort will lead to success.

Controllability: he/she feels failure is uncontrollable, becomes aggressive, and feels helpless and reluctant to work as he assumes he will not produce any quality work. A teacher may convey unintended messages when he/she shows annoyance with unsuccessful students. Such annoyance gives the message that the student had the ability to perform but did not succeed. When the teacher shows sympathy, such an attitude tells the student that even with the effort he/she does not have the ability to succeed. High school or college students want to preserve their egos and when they fail, they claim that they did not apply sufficient effort when completing a task. When they succeed, on the other hand, they want to be considered “smart” (Fwu et al., 2018).

Attributions are complicated and have important implications for how people see themselves and others. However, certain attributional biases lead to inaccurate judgments of whether the cause is internal or external.

3. Methods

A mixed-methods research design was utilized with qualitative and quantitative characteristics as proposed by Creswell and Clark (2011). The qualitative sample was much smaller than the quantitative sample and it helped the researcher to get a better in-depth discussion through interviews and a “rigorous” quantitative investigation of the topic.

The explanatory design as highlighted by Creswell and Clark (2011) for the mixed-method study was used. The quantitative data was first collected through questionnaires, thereafter it was analysed, and then this was followed up with smaller qualitative data collection.

Research strategy: Instruments used in this research study were questionnaires and interviews. The quantitative method used in the research is the survey design. The data collected in this study were through questionnaires (quantitative) and face-to-face interviews (qualitative) as supported by Maree (2010). The study investigated the learners’ ability, effort, task difficulty and luck attribution styles and their effect on achievement in science.

Population and sampling: Table 1 below provides details about the population and sample. The target population included high schools in two educational regions of the North-West Province of South Africa (n=60).

The sample used in the study was s=30.

A systematic random sampling method was used to pick a sample of 1773 Grades 10 to 12 science learners from 30 of the 60 schools. This sample was representative in that it constituted 15% of the population. In total 1773 questionnaires were distributed to the learners.

Purposive sampling technique was used to select 5 teachers from the teaching staff and 5 Physical Scienceslearners for interviews. Edmonds and Kennedy (2013) advise that purposive sampling provides in-depthdata pertaining to the research questions posited in a study. Hence, there were 10 interviews that wereconducted to supplement the learners’ views on the attribution stance.

Table 1. Population and sample

-

Schools in NW Schools Learners Population 60 11 748 Sample 30 1 773

Instrumentation: Quantitative data were collected using close-ended questions, while open-ended questions were utilized in the qualitative interviews as supported by Edmonds and Kennedy (2013). The Attribution Questionnaire was used to identify the attributional styles of learners on the science achievement oflearners. The Likert Scale was used to measure the strength of four attributional factors: ability, eff ort, taskdiffi culty and luck. The percentage achieved in the physical science test was indicated in the questionnaire.Learners who achieved 70% and above in their science test were classified as high achievers, whereas learners who achieved below 39% were classified as low achievers.

The physical science learner respondents in this study chose one of four options in the Attribution Ques-tionnaire to indicate the type of attributions that aff ect their achievement in science. There were four fac-tors of attributions which included: ability, effort, task difficulty and luck attribution. For example, the respondents indicated whether their science test mark was due to ‘no ability’, ‘little ability’, ‘more ability’ or ‘a lot of ability’. For the qualitative interviews, 5 teacher respondents and 5 learners gave their opinions on whether learners had the ability, exerted a lot of effort in the preparation of the physical science test andwere interested in science. They also gave their opinions on the test difficulty and whether or not they werelucky in achieving the results that they did.

Data collection and administration: The questionnaires were hand-delivered after prior appointments had been made with the principals at the respective schools. They were administered to 1773 respondents from the two educational regions of the North-West Province. The purpose of the study and the procedures in completing the questionnaires was explained with the assistance of teachers at the relevant schools. The purpose of the interview, data-collection technique of recording interviews and duration of the interviews was explained to the teachers and learner respondents at each school. All respondents were proficient in English and they were able to express their feelings and opinions freely.

Respondents explained how important each of the attributional factors was in affecting their achievement in science. During the interviews, the researcher probed respondents in a bid to get a full understanding ofthe learners’ explanations on how attributions influenced their achievement in science. The teachers an-swered questions related to the attributional styles of Grades 10 to 12 physical science learners. The interviews were captured for transcription, analysis and interpretation. Questionnaires were collected immediately after administration.

Data processing: Quantitative and qualitative techniques were applied in analysing data. Statistical consultants assisted in organizing and analysing data.

Quantitative data were gathered from the questionnaires which were administered to the science learners. Interview questionnaires were transcribed qualitatively.

Data were interpreted using simple descriptive statistics and raw data were captured and presented in tables and bar charts. Frequencies and percentages were calculated to represent data. Statistical methods such as the Chi-Square Test, Analysis of Variance (ANOVA) and the Pearson coefficient of correlation test were used to interpret the data.

Ethical considerations: Letters of consent to conduct the research study were obtained from: the District Manager to go to sampled schools; school principals to conduct the research; from school principals to conduct the interviews with learners and teachers. Respondents gave permission for recording of interviews, were made aware of the purpose of the interviews that their participation was voluntary, and they were assured of anonymity and confidentiality.

In this study, the researcher ascertained that all respondents were proficient in English so that they could complete the questionnaires and the learners were able to voice their feelings and opinions freely.

Trustworthiness: To ensure the reliability and validity of the instruments in this study, a pilot study was conducted by using a different sample of learners from Grades 10 to 12 who were not included in the final testing. The questionnaires were pre-tested at two high schools to establish the clarity and relevance of the questions. To supplement the questionnaire findings, interviews were conducted to validate the data quality.

4. Results

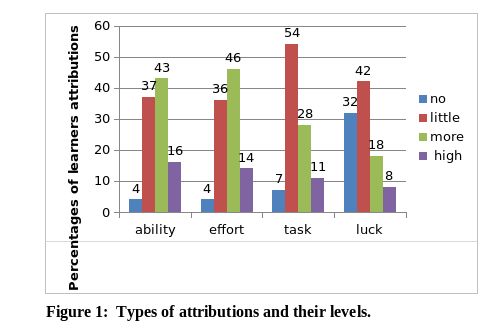

Figure 1 represents the four attribution factors in terms of levels of attributions. The four levels are categorized on a continuum from ‘no’, ‘little’, ‘more’ to ‘high’ levels of each factor of attribution. The factors of attribution are as follows: ability, and effort (internal attributional style), task difficulty and luck, (external style of attribution).

The respondents were requested to rate each one of the four attribution factors regarding their influence on their performance and thereafter rank the attribution in its relation to science achievement.

Results in Figure 1 indicate that most of the science learners made the highest attribution to ‘more ability’ (43%), and ‘more effort’ (46%). The attribution factors ability and effort constitute an internal attribution style therefore, most science learners made high internal attributions. In addition, the figure indicates that the science learners used less external attributions by making less task difficulty (54%) and less luck (42%) attributions.

The internal (ability and effort) and external attributions (task difficulty and luck) were assessed in terms oflow achievers (0-39%) and high achievers (70-100%) in science. Table 1 demonstrates the ability attributions of high, average and low achievers. In terms of high versus low achievers, the current study demonstrates that high achievers made higher ability attributions (30%) than low achievers (13%). On the other hand,more low achievers (45%) believed that they had no ability in science compared to 10% of high achievers.

Table 1: Ability Attributions of Science learners

-

Ability Attributions High achievers % Average achievers % Low achievers % Total %

No ability 10 45 45 100 Little ability 6 67 27 100 More ability 20 66 14 100 High ability 30 57 13 100

Table 2 depicts the effort attributions of high, average and low achievers. In terms of high versus low achievers, the current study demonstrates that successful high achievers tend to make higher effort (35%) attributions than low achievers in the failure condition (12%). Furthermore, more low achievers (46%) than high achievers (8%) made a lack of effort attributions.

Table 2: Effort Attributions of Science Learners

-

Effort attributions High achievers % Average achievers % Low achievers % Total %

No effort 8 46 46 100 Little effort 8 65 27 100 More effort 17 68 15 100 High effort 35 52 12 100

Table 3 displays the task difficulty attributions of high, average and low achievers. In terms of high versus low achievers, more high achievers (35%) than low achievers (15%) found that the test was not difficult. On the other hand, more low achievers (37%) who failed than high achievers (11%) found the science test extremely difficult.

Table 3: Task Difficulty Attributions of Science Learners

-

Task difficulty Attributions

High achievers % Average achievers % Low achievers % Total %

No task difficulty 35 50 15 100 Little task difficulty 18 65 17 100 More task difficulty 10 71 19 100 High task difficulty 11 52 37 100

Table 4 reveals the luck attributions of high, average and low achievers. In terms of high versus low achievers, more low achievers (25%), who failed in science, than high achievers (16%) made no luck attributions. On the other hand, more high achievers (29%) and less low achievers (15%) tended to attribute their out-come to high luck. The study indicated that high achievers attributed their success to high luck and low achievers attributed their failure to lack of luck.

Table 4: Luck Attributions of Science learners

-

Luck Attributions High achievers % Average achievers Low achievers %

Total %

No luck 16 59 25 100 Little luck 14 66 20 100 More luck 13 72 15 100 High luck 29 56 15 100

The Pearson correlation coefficient test applied to the findings indicates a positive relationship between ability, effort, task difficulty and luck attributions relative to science achievement. Since the p-value that was obtained for all these attribution levels of 0.000 is less than the 0.05 level (P<0.05; df = 6), it means that statistically, the result is significant, implying that there is a significant relationship between ability, effort, task difficulty, luck attributions relative to achievement in the science subject.

Table 5: Chi-Square results for four Attributions

-

Attributions Pearson Chi-Square Attributions Pearson Chi-Square Ability 139.201a Task difficulty 89.977a Effort 158.635a Luck 36.583a Task difficulty 89.977a Task difficulty 89.977a Luck 36.583a Luck 36.583a

An ANOVA test of significance was performed on the four attributions. The ANOVA test applied to the findings indicates a positive relationship between attributions and science achievement. Since the obtained p-value for all these attribution levels of 0.000 is less than the 0.05 level (P<0.05; df = 6), it means that statistically, the result is significant, implying that there is a significant relationship between ability, effort, task difficulty, luck attributions relative to science achievement (see Table 6).

Table 6: ANOVA test of significance for four Attributions

| Attributions | Df | F | Sig. |

| Ability | 6 | 35.562 | .000 |

|

Effort |

6 | 40.169 | .000 |

| Task | 6 | 13.465 | .000 |

| Luck | 6 | 5.633 | .000 |

A regression model was developed to act as a concise summary for the individual ANOVAs and Chi-Square scores, where their inter-relationships are catered for. The model seems to be moderate with (R = 0.189),where all variables are significant since p-values are all less than 0.05. Equally so, all variables contribute significantly to the model. The regression model can only explain 19% of the variation of the learners’achievement in science; it cannot be used to predict, but for exploratory purposes, it explains that all the attributions contribute positively to achievement in science.

All findings in the present study were elaborated during the focus group discussions and interviews with the educators and learners. The results are discussed in detail below.

5. Discussion

The present study indicated that high achievers attributed their success to high ability, hard work, and high luck and low achievers attributed their failure to lack of ability, inadequate effort and lack of luck. These findings are in harmony with those of Batool et al., (2012).

The findings were elaborated during the focus group discussions and interviews with the educators and learners. Educators believed that high achievers had the high ability and exerted a lot of eff ort, whereas low achievers lacked both ability and effort. Learners indicated that they had little to high ability to perform well in science. It is likely that high achievers who made unstable effort attributions for success will put in more effort in the task for them to succeed, and if they believe it was due to ability, they will then use more effort to succeed.

The findings in the current study are in agreement with Fwu et al., (2018) who noted that failure may be ascribed to lack of effort which is subject to volitional control. Several other theories (Manzoor & Mahmood,2019; McClure et al., 2010; Likupe, & Mwale, 2016; Cook & Artino, 2016) also confirm that most respondents made the highest attributions to internal effort and ability factors. High achievers attributed their success to effort, whereas low achievers made lack of effort attributions.

Research has shown that locus and stability dimensions determine expectancy of future success or failure. In the present study low achievers’ attributions to low ability (internal, stable cause) may lead to learners anticipating future failure. However, the failure attribution to an unstable factor (insufficient effort exerted on the task) may lead to failure not being anticipated (Fwu et al., 2018)). In the future learners are likely to spend more effort on the task and expect to succeed.

The findings in the present study are also in line with the findings of Chen et al, (2016) and Fwu et al., (2018)who found that successful learners attributed their success to task ease. The high subject difficulty attributions (stable, external, uncontrollable) for failure by low achievers in the present findings may lead to higher expectations of future failure (Chen et al., 2016; Fwu et al., 2018).

Interview results indicate that educators believe that high achievers found no difficulty in science. Learners who spent sufficient effort on the science preparation found no difficulty with the science subject. The results of this study are in harmony with other researchers who have established that science is a difficult course because learners are not encouraged at home or in school to pursue science as a career (Rozek &Svoboda, 2017; Aschbacher et al., (2010).

The present study demonstrated that high achievers attributed their success to high luck and their failure to lack of the same (unstable, external). The current findings also concur with studies that show that some of the learners use luck attributions to explain their success or failure (Hawi 2010; Weiner, 2010; Batool et al., 2012). Failure attributions to no luck (external unstable) factors in the current study are not likely to lead to better performance in future.

The results of the present study are consistent with Weiner’s theory that low achievers had an external locus of control that associated their outcomes in science with external luck and task difficulty factors. During the interviews, educators believed positive outcomes in tests were not due to luck, but a lot of effort was spent on test preparation.

Based on the findings of the study it is evident that attribution and science achievement were strongly related. The Pearson correlation coefficient test applied to the findings indicates a positive relationship between ability, effort, task difficulty and luck attributions relative to science achievement. Since the p-value obtained for all these attribution levels of 0.000 is less than the 0.05 level (P<0.05; df = 6), it means that statistically, the result is significant, implying that there is a significant relationship between ability, effort, task difficulty, luck attributions relative to science achievement.

6. Conclusion

Data collected were analysed mainly through quantitative methods. The qualitative interviews with a princi-pal, Heads of Departments, 5 teachers and Physical Science learners helped with the triangulation process. ANOVA and Chi-Square statistical techniques were used to analyse the quantitative data. The results show that attributional styles internal (ability, effort, and external (task difficulty, luck) attributions affect learners’achievement. The quantitative questionnaire findings and the qualitative interview results show that attributions affect the science achievement of learners.

7. Recommendations

It is recommended that learners become aware of types of attributions (ability, effort, task difficulty, luck) that affect the achievement of learners in science subjects in Grades 10 to 12. An internal attributional style results in higher achievement. Therefore, it is recommended that learners be encouraged to adopt an internal attributional style by stressing ability and effort attributions.

Science educators should stress effort attributions, as effort enhances learners’ academic achievement. Effort attribution is adaptive and leads to better expectations of the future performance of the learner.Causes such as effort can be changed, whereas other causes such as luck and ability cannot be changed intentionally.

8. References

Aachbaker, P. R., Li, E. & Roth, E.J. 2010. Is science Me? High School Students’ Identities, Participation and Aspirations in Science, Engineering, and Medicine. Journal of Research in Science Teaching. 47(5): 564–582.

Basturk, S. & Yavuz, I. 2010. Investigating causal attributions of success and failure on Mathematics instructions of students in Turkish High Schools.

Procedia Social and Behavioural Sciences. 2(2): 1940-1943.

Batool, S., Manzoor, R., Arif, H. & Naseer, U.D. 2010. Gender differences in achievement attributions of mainstream and religious school students.

International journal of academic research,

2. 6. Part II.

Batool, S., Muhammad, I.Y. & Qaisara, P. 2012. A Study of Attribution among High and Low Attribution groups: An application of Weiner’s Attribution Theory. Anthropologist, 14 (3): 193-197.

Chen, S.W., Fwu, B.J., Wei, C.F. & Wang, H.H. 2016. High-school teachers ‘beliefs about eff ort and their atti-tudes toward struggling and smart students in a Confucian society. Frontiers in Psychology.http://dx.doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2016.01366.

Cook, D.A. & Artino, Jr, A.R. 2016. Motivation to learn: an overview of contemporary theories.

Medical education, 50 (10): 997-1014.

Creswell, J.W. & Clark, V.L.P. 2011. Designing and conducting: mixed methods research . Los Angeles: SAGE.

Cuevas, J.A., Irvinng, M.A. & Russell, L.R. 2014. Applied cognition: Testing the eff ects of independent silentreading on secondary students’ achievement and attribution. Reading Psychology, 35(2), 127–159.doi:10.1080/02702711.2012.675419

Edmonds W.A. & Kennedy, T.D. 2013. An applied reference guide to research designs: quantitative, qualitativeand mixed methods.

Los Angeles: SAGE.

Fishman, E.J. & Husman, J. 2017. Extending Attribution Theory: Considering Students’ Perceived Control ofthe Attribution Process.

Journal of Educational Psychology, 109(4): 559-573.

Frijters, J.C., Tsujimoto, K.C., Baoca, R., Gottwald, S., Hill, D., Jacobson, L.A. & Bosson‐Heenan, J. 2018. Reading‐related causal attributions for success and failure: Dynamic links with reading skill.

Reading research quarterly, 53 (1): 127-148.

Fwu, B.J., Chen, S.W., Wei, C.F. & Wang, H.H. 2018. I believe; therefore, I work harder: The significance of reflective thinking on effort-making in academic failure in a Confucian-heritage cultural context. Thinking Skills and Creativity, 30, 19-30.

Graham, S. & Chen, X. 2020. Attribution Theories. In Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Education. DOI:10.1093/acrefore/9780190264093.013.892. 1-21.

Hawi, N. 2010. Causal attributions of success and failure made by undergraduate students in an introductory-level computer programming course. Computers and Education, (54): 1127-1136.

Heider, F. 1958. The psychology of interpersonal relations. New York, Wiley.

Hewett, R., Shantz, A., Mundy, J. & Alfes, K. 2018. Attribution theories in human resource management re-search: A review and research agenda.

The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 29 (1),pp.87-126.

Igbaakaa, J.A. 2019. Influence of Psychological Ownership, Locus of Control and Leadership Styles on Deviant Behaviour among Staff of Benue State Internal Revenue Service (Doctoral dissertation).

Kelley, H.H. 1967. Attribution in social psychology. (In Levine, D. (ed). Nebraska Symposium on motivation.Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press.

Manzoor, S. & Mahmood, A. 2019. A Comparative Study of High and Low Achievers of MA English: An Attri-bution Theory Perspective.

Journal of Research in Social Sciences, 7 (1): 30-43.

Maree, K. 2010. First steps in research. Pretoria: Van Schaik Publishers.

Mcclure, J., Meyer, L.H., Garisch, J., Fischer, R., Weir, K.F. & Walkey, F.H. 2010. Students’ attributions for theirbest and worst marks: Do they relate to achievement? Contemporary Educational Psychology. Journal Homepage, Article in Press, School of Psychology. Victoria: University of Wellington, New Zealand.

Mudhovozi, P., Gumani, M., MuanganidzeE, L. & Sodi, T. 2010. Causal attribution: actor-observer bias in aca-demic achievement among students at an institution of higher learning. South African Journal of Higher Education, 24(4): 585-601.

Nathaniel, B. 2019. The power of self-esteem.

Nenty, H.H.J. 2010. Analysis of Some Factors that Infl uence Causal Attribution of Mathematics Achievementamong Secondary School Students in Lesotho. Journal of Social Science, 22 (2): 93-99.

Rotter, J.B. 1966. Generalized expectancies for internal versus external control of reinforcement. Psychological Monographs, 80: 1– 28.

Rozek, C.S., Svoboda, R.C., Harackiewicz, J.M., Hulleman, C.S. & Hyde, J.S. 2017. Utility-value intervention with parents increases students’ STEM preparation and career pursuit.

Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 114 (5): 909-914.

Rusillo, M.T.C. & Arias P.F.C. 2004. Electronic Journal of Research in Educational Psychology, 2(1): 97-112.

Soriano‐Ferrer, M. & Alonso‐Blanco, E. 2020. Why have I failed? Why have I passed? A comparison of students’ causal attributions in second language acquisition (A1–B2 levels). British Journal of Educational Psychology, 90 (3), pp. 648.

Weiner, B. 2010. The development of an attribution-based theory of motivation: A history of ideas. Educational Psychologist, 45: 28-36.