Dr. Burgert Senekal, University of the Free State

Ensovoort, volume 45 (2024), number 08: 1

Abstract

Heilung forms part of a new group of folk music bands, along with Wardruna, that straddles the divide between folk music and metal, all while using Germanic texts from the Middle Ages and earlier in their music. The current article investigates the origins of the lyrics in one of Heilung’s most famous songs, “In Maidjan.” Every line is traced to early Germanic inscriptions, most of which were written in the elder futhark, and various scholarly interpretations are provided. Lastly, it is shown that Heilung combines these early Germanic inscriptions to construct a song with magical Norse/Germanic Pagan connotations that frames the historical use of the elder futhark.

Keywords: Heilung, NeoFolk, Dark Nordic Folk, Germanic language, runes, runic inscriptions, elder futhark

Introduction

Recent decades have witnessed a revival in interest in Norse Pagan culture, partly influenced by popular television series such as Vikings (2013-2021) and a new wave of folk music. Bands such as Heilung, Wardruna and Nytt Land use old Germanic texts in their lyrics, combining and reinterpreting these texts for a modern audience. The movement has gained a significant following, with Heilung, Wardruna and Nytt Land for instance having 253,000, 303,000 and 22,300 followers respectively on Instagram, and 600,533, 615,410 and 50,149 followers respectively on Spotify (as on 8 January 2024).

The current article discusses the origins of the lyrics used in Heilung’s song, “In Maidjan,” focusing on which runic inscriptions are used and the difficulties involved in interpreting these inscriptions. The article also shows that even though the song was first recorded in 2015, the texts it uses constitute the earliest Germanic inscriptions and therefore this song may be regarded as the oldest Germanic song that is currently known, at least in terms of its lyrics.

Background to Heilung

Heilung was founded in 2014 by Kai Uwe Faust (from Germany), Christopher Juul (Denmark) and Maria Franz (Norway) (Roe 2019:19). Although using traditional instruments, clothing and Pagan ritual performances, Heilung is usually discussed as a metal band and also performs at metal music festivals (Roe 2019:15). Roe (2019:15) refers to Heilung’s occupation of a “liminal space,” “between pagan-inspired folk music and extreme metal.” The band is often singled out alongside Wardruna as instrumental in the current revival of Norse Paganism, and their importance as a NeoFolk or Dark Nordic Folk band in the growing Norse Pagan revival is discussed in Roe (2019), Fitzgerald (2023) and Fitzgerald and Nordvig (2023), with numerous mentions in Arntzen (2023). To date, Heilung has released four albums: Ofnir (2015/2018), Lifa (2018), Futha (2019), and Drif (2022) (Ofnir was originally self-released, but later rereleased under the label Season of Mist). The song, “In Maidjan,” was included on their live album, Lifa (2018), and on their first studio album, Ofnir (2015/2018).

Trafford (2021) highlights the importance of using dead languages — languages that are no longer spoken — in the contemporary folkmetal (which includes the Dark Nordic Folk) music scene. Using these languages creates a sense of authenticity and delineates bands from the contemporary world. Trafford (2021:227) argues,

Dead language use in the folk metal scene proper is of a rather different sort. Latin is seldom deployed; on the contrary, when folk metal bands use dead languages as a rule they use one, vernacular, language, namely that associated with their own nation of origin in its earliest and formative period. It is particularly notable that the dead languages of choice for folk metal bands are almost never the relatively recent later medieval forms but almost invariably the languages of the remote past, frequently the first millennium CE or earlier, traditionally seen as Europe’s ethnogenetic period, in which the nations of the continent first emerged.

While Trafford (2021) does not mention Heilung, Heilung often incorporates early Germanic texts in their work. On the album Futha (2019), the song “Norupo” is a setting of the thirteenth century Norwegian Rune Poem (Norupo is an abbreviation of NOrwegian RUne POem), which provides an exposition of the sixteen runes of the younger futhark (for a discussion of this poem, see Szőke 2018). On the album Drif (2022), Heiling includes the song “Anoana”, which is a reference to the runic inscription on the Norway B-Bracteate, found in Norway and dating to the mid 5th to mid 6th centuries, which reads, anoana in the runes of the elder futhark (Roost 2021:163). It is also noteworthy that album names are spelled in runes on the covers of all their albums, and all album covers use the elder futhark. Compare ᛟᚠᚾᛁᚱ (elder futhark) rather than ᚬᚠᚾᛁᛦ (younger futhark) (Ofnir), ᛚᛁᚠᚨ rather than ᛚᛁᚠᛅ (Lifa), ᚠᚢᚦᚨ rather than ᚠᚢᚦᛅ (Futha), and ᛞᚱᛁᚠ rather than ᛏᚱᛁᚠ (Drif).

Heilung’s musical performances are ritualistic in nature, and Fitzgerald (2023:66) notes their “ritualized live performances” and “striking regalia.” Fitzgerald (2023:149) writes that their performances are partly rituals in themselves,

Heilung actively narrate their performances as ritual experiences and uphold this narrative by dressing in intricate regalia inspired by the Nordic Iron Age, providing opening and closing prayers to their performances, and by performing small rituals throughout their sets such as the burning of bundles of herbs and spreading the smoke throughout their performances space and over the audience with an eagle feather fan.

Heilung have also ceremoniously sanctified their instruments with their own blood, among which their big drum, called “Blod” (blood) (Fitzgerald 2023:42).

Using material dating back to the earliest runic inscriptions, Heilung’s lyrics are often open to interpretation. Düwel (2004:127) argues, “There is hardly a single inscription of the older runic period that has an agreed reading, let alone an agreed interpretation.” Importantly, Juul remarks in an interview (quoted in Roe 2019:29), “We do not wish to give exact translations or explanations, because those are still open for great discussion in the scientific community.” This acknowledgement of the difficulty with interpreting early runic inscriptions has special significance for the current study, as is shown later.

“In Maidjan” is one of Heilung’s songs that has been most visible in popular culture. The song was used for the marketing video of the video game, Senua’s Saga: Hellblade II, and this song was also used on the soundtrack of the television series, Vikings (Season 6, episode 20) (Senekal 2021:140). This song also uses the oldest Germanic language material, as is discussed in the current article.

Methods

To determine the origin of the lyrics of “In Maidjan,” various comprehensive and authoritative sources on runes from the elder futhark were consulted. These include Krause (1971), Antonsen (1975), Makaev (1996), Düwel (1998, 2004, 2008), Looijenga (2003, 2020), and Roost (2021). For word etymologies, the comprehensive works by Orel (2003), Kroonen (2013), and Pokorny (2007) were used. Lastly, interpretations were supplemented by incorporating various scholarly publications on the runes.

In maidjan

The title of the song refers to Proto-Germanic *maidjan, “to damage, hurt”, cognate with Old Norse meiða, “to hurt; to damage, destroy” (Orel 2003:254; Kroonen 2013:347). Orel (2003:254) provides the Indo-European root as *maiđjanan and relates the word to Gothic maidjan, “to alter, to falsify”. The title therefore implies damaging or hurting someone, perhaps through falsification.

The lyrics to “In Maidjan” are given below, as provided by https://www.musixmatch.com/lyrics/Heilung/In-Maidjan. The Lifa and Ofnir versions of the song only differ in performance; their lyrics are identical.

- Harigasti Teiwa

- Tawol Athodu

- Ek Erilaz

- Owlthuthewaz

- Niwaremariz

- Saawilagar

- Hateka Harja

- Fehu Uruz Thurisaz Ansuz Raidho Kenaz

- Gebo Wunjo Hagal Naudhiz Isa Jera

- Eihwaz Perthro Algiz Sowelu Tiwaz Berkano

- Ehwaz Mannaz Laguz Ingwaz Dagaz Othala

- Wuotani Ruoperath[1]

- Gleiaugiz Eiurzi

- Au Is Urki

- Uiniz Ik

I mostly follow Roost’s (2021) transliteration when citing runic inscriptions below. As suggested by Düwel (2004:123) and Knirk (2002:635), transliterations are written in bold.

Harigasti Teiwa

The song starts with a call, Harigasti Teiwa! This call is from the Etruscan inscription on the Negau helmet B, discovered by Jurij Slaček in Slovenia in 1811, which reads, hariχastiteiwa (Reichardt 1953:306; Sanders 2010:26; Hansen and Kroonen 2022:152; Mees 2022:29). The date of the helmet is uncertain, with estimates between the late 4th century BCE and 6-9 CE (Mees 2022:27). This inscription was identified by Kretschmer (1929) as the oldest Germanic text ever discovered, and is still generally considered to be the earliest written Germanic found to date (Reichardt 1953:307; Sanders 2010:26; Hansen and Kroonen 2022:152). It should be emphasised that unlike the other lines of this song, it was not written down in runic, but rather in the Etruscan script.

The inscription on the Negau helmet B has been interpreted in various ways, including that the maker of the helmet is called Harigast, that the intended user of the helmet is called Harigast, or that Harigast may be a name of a god (or perhaps an alternative name for Óðinn) (Krause 1971:115; Sanders 2010:26). Harigast may also be linked to the Germanic words harja (“army”) and gastiz (“guest”) (Reichardt 1953:307; Hansen and Kroonen 2022:152; Mees 2022:29). Orel (2003:163) provides the Proto-Germanic root for harja as *xariz ~ *xarjaz, cognate with Gothic harjis (“army”) or Old Norse herr (“host, people, army”) (see also Kroonen 2013:211). The root of gastiz is *उastiz, cognate with Gothic gasts (“stranger, guest”) or Old Norse gestr (“guest”) (see also Kroonen 2013:170). Teiwa is reminiscent of Old Norse tívar (“gods”), Norse Mythology Týr, and Proto-Germanic Teiwaz (Mees 2022:29) or tīwa (“god”) (Kroonen 2013:519).

The line, “Harigasti teiwa” may therefore mean “guest of the army, god,” but other interpretations are equally possible.

Tawol Athodu

The second line, Tawol Athodu, occurs on the Trollhättan A-Bracteate, found in Sweden and dating to the mid 5th to mid 6th centuries CE (Antonsen 1975:63; Roost 2021:185). The original inscription, written in the elder futhark, can be transliterated as tawo l | aþodu, usually divided as tawo laþodu (Krause 1971:168; Antonsen 1975:63; Roost 2021:185).

The word tawo means “I make” (Roost 2021:185) or “prepare” (Krause 1971:168; Antonsen 1975:63), with root word *tawjanan (“to make”) (Gothic taujan, “to do, to make”), and also occurs as tawido in runic inscriptions (Orel 2003:403; Kroonen 2013:511). The word, laþodu, is a form of laþu, which is often used as a charm word (Roost 2021:185), which Looijenga (2003:199) translates as “invitation, summons.” Corresponding to Old Norse lǫð (“invitation”), laþu (*laþōjan in Kroonen 2013:328) is believed to symbolise a ceremonial calling for assistance or summoning, most likely in reference to the deity pictured on the bracteate (Looijenga 2003:30; Roost 2021:93). Düwel (2008:47) interprets the inscription as “I extend an invitation,” arguing that the text statement captures a speech act by the god in the performance of one of his rituals, here the summoning of his animal-shaped helpers. Similarly, Antonsen (1975:63) translates the inscription as “I prepare the invitation,” Krause (1971:168) translates it as, “Ich bereite eine Zitation,” and Hauck (1998:335) translates the inscription as, “ich nehme eine Zitation vor.”

The line, “Tawol Athodu” is therefore a clear magical or spiritual incantation, meaning more or less, “I make an invitation.”

Ek Erilaz

The Lindholmen Amulet, found in Sweden (dated to 350 – 550 CE (Düwel 2008:29)), reads, ek erilaʀ Sa(wil)agaʀ ha[i]teka ‘ | …’ alu’, in the elder futhark (Hultgård 1998:718; Looijenga 2003:165; Roost 2021:157). The statement, Ek erilaz, is however also found in a number of other runic inscriptions, such as on the Etelhem Fibula (Sweden, 450–520 CE) ((e)k (e)r(i)laʀ w[o]rt(a) (1?)) (Roost 2021:136), the Järsberg Runestone (Sweden, unknown date) (ekerilaʀ) (Roost 2021:150), the Bratsberg Fibula (Norway, 490–540 CE) (ek erilaʀ) (Roost 2021:127), the By Runestone (Norway, unknown date) (ek erilaʀ Hroʀaʀ Hroʀe wo(r)te þat aʀina […] rṃ̣þ) (Roost 2021:127), the Eskatorp F-Bracteate (Sweden, mid 5th to mid 6th century (f(a)hid(o) wilald (W)igaʀ e[k] erilaʀ) (Roost 2021:136), the Kragehul spear shaft (Denmark, 450-475 CE) (ek Erilaʀ A[n]sugisal(a)s muha haite ga ga ga …hagal(a) wiju) (Roost 2021:154), the Veblungsnes Cliff (Norway, unknown date) (ek (I)rilaʀ Wiwila(n)) (Roost 2021:191) and the Trollhättan II C-Bracteate (Sweden, mid 5th to mid 6th centuries) (‘ eekrilaʀ ‘ Mariþeubaʀ haite ‘ wrait alaþo) (Looijenga 2020:826; Roost 2021:186). Given the rest of the inscription on the Lindholmen Amulet and lines 6 and 7 of “In Maidjan,” the Lindholmen Amulet is however the most likely source text for the song.

Ek is the archaic Germanic first person pronoun (Looijenga 2003:165; Poruciuc 2020:21), cognate with Gothic ik and Old Norse ek (Orel 2003:83; Kroonen 2013:116).

The meaning of erilaz is less certain. Looijenga (2003:352) emphasises that erilaz is not a personal name, given its wide occurrence, and in addition, erilaz often occurs alongside a name, suggesting that it may be a title (Hultgård 1998:718; Roost 2021:40). Krause (1971:143) argues that the word means, “the Runemaster,” leading to an interpretation of the amulet as, “Ich, der Runenmeister hier, heiße Listig” (1971:155) (see also Düwel, Nedoma and Oehrl 2020:140). While Antonsen (1975:36) calls the word “etymologically obscure,” he cites Indo-European cognates meaning “messenger,” “eagle” and “arise.” It is also possible that erilaz may signify a connection with the Germanic tribe of the Heruli (Krause 1971:143; Makaev 1996:39; Benoist 2018:58), although this is questioned by Hultgård (1998:817). Erilaz is sometimes translated as earl, indicating a title (Looijenga 2020:826), but Hultgård (1998:817) emphasises that this relationship is etymologically unclear. Hultgård (1998:817) claims that erilaz is a title linked with some religious function, “Meines Erachtens gehört das Wort erilaR in die kultisch-religiöse Sphäre und bezeichnet dabei eine kultische Funktion bzw. ein Götterepitheton.” Roost (2021:40) argues that erilaz can only with certainty be equated with a title; further interpretations become more speculative. Incidentally, the Meldorf fibula, dating to 50 CE and perhaps the oldest runic inscription (see below), could read irile, which Mees (2012) claims could mean “to the runemaster”, although Roost (2021:159) calls this interpretation “highly speculative.”

This line in “In Maidjan” therefore means “I, the erilaz” with certainty, while keeping in mind that the erilaz may be a religious title.

Owlthuthewaz

Line 4 of “In Maidjan” refers to the bronze sword chape known as Thorsberg I, which was found in Schleswig-Holstein, Germany, dated to 200 CE (Antonsen 1975:29; Looijenga 2003:259; Düwel 2008:26). The inscription, written in the elder futhark, reads, owlþuþewaz on the one side, and niwajemariz on the other (Antonsen 1975:29; Looijenga 2003:259; Düwel 2008:26).

Looijenga (2003:259) and Williams (1998:604) aver that the inscription can be related to the Proto-Germanic Wolþu (“exuberance, sumptuousness”) and þewaz (“servant”). The inscription may also relate to inherited property of the named person (W(u)lthuthew), and in this case it is unclear whether a secular or divine entity is referred to (Düwel 2008:26). To Antonsen (1975:30) and Krause (1971:167), Wolþuþewaz may be a servant of Ullr. Williams (1998:604) however believes that this part of the Thorsberg inscription only refers to a person’s name.

This line of “In Maidjan” is therefore impossible to interpret with certainty, and may refer to a servant of Ullr, someone’s property or only to a person’s name.

Niwaremariz

Niwaremariz is also found on the Thorsberg I sword chape (Looijenga 2003:259; Düwel 2008:26). Krause (1971:167) translates niwajemariz as “nicht-schlechtberühmt,” Antonsen (1975:30) as “of immaculate repute,” and Düwel (2008:26) as “der nicht schlecht Berühmte”. Antonsen (1975:30) then translates the inscription on the sword chape as, “Wolþuþewaz [servant of Ullr] of immaculate repute,” and Krause (1971:167), “Erbbesitz. W., der Nicht-Schlechtberühmte.”

This line of “In Maidjan” therefore means “of good repute” with a large degree of certainty.

Saawilagar

As noted earlier, Saawilagar refers to the Lindholmen Amulet. According to Antonsen (1975:37), Saawilagar means “sunny one”, leading him to interpret the inscription on the amulet as, “I, the erilaz, am called Sawilagaz [i.e. the sunny, bright one].” Hultgård (1998:718) also interprets the Lindholmen Amulet as meaning, “Ich erilaR, sawilagaR heiße ich,” but notes that it is in all likelihood not a personal name, but rather a nickname or epithet (see also Mees 1999:146). It is possible that Sawilagaz may be an epithet for a god.

This line in “In Maidjan” therefore refers to “The sunny one,” whoever that may be.

Heilung does not use the entire runic inscription from the Lindolmen Amulet, but it should be noted that this inscription ends with aaaaaaaazzznnn?muttt:alu (Looijenga 2003:166, 2020:831). According to Looijenga (2003:166, 2020:831), the repetition of a, z, n and t is meaningful given the names of these runes, *ansuz (“god”), *algiz (“elk”), naud (“need, needful”), and *Tyr. Their repetition may suggest an incantation (see also Mees 1999:146 and Hultgård 1998:724). This interpretation is supported by the final alu: Looijenga (2020:831) notes that while the meaning of this word is obscure, it may be etymologically related to Greek αλειν (“to be beside oneself”) and Hittite *alwanzatar (“magic”) (Antonsen 1975:37 also translates alu as “magic”). In later Germanic languages, alu may have become ale, and Looijenga (2020:831) argues that the word could have meant “ecstasy” before it came to designate an alcoholic drink (see Roost 2021:88-92 for a detailed discussion of alu). In any case, even though Heilung omitted this part of the runic inscription on the Lindolmen Amulet, the repetition of runes and the use of alu suggests that this inscription has a magical function, and Mees (1999:146) avers that “the sequence of repeated runes on the Lindholm piece seems to indicate some sort of cryptological, or considering later magical practices, a magico-religious expression.” Despite Heilung’s omission of this section of the inscription, then, the inclusion of the Lindholmen Amulet as source text shows that “In Maidjan” has a magical connotation.

Hateka Harja

Like Saawilagar, hateka refers to the runic inscription on the Lindholmen Amulet. Hateka is generally translated as “am called” (Antonsen 1975:37; Looijenga 2003:166, 2020:826; Roost 2021:130), from Proto-Germanic *haitan (“to call”) (*xaitanan in Orel 2003:153), cognate with Gothic haitian and Old Norse heita (Kroonen 2013:202).

Harja is found on the Vimose Comb, found in Denmark and dating to around 150 CE (Looijenga 2003:38; Düwel 2008:24; Roost 2021:193). This is also the oldest runic inscription that can be dated with certainty (Looijenga 2003:38; Düwel 2004:139; Price 2015:301); the Meldorf fibula (dating to around 50 CE) has not been conclusively demonstrated to be a runic inscription (Looijenga 2003:38; Düwel 2004:139; Roost 2021:159).

Harja may refer to the Germanic tribe, the Harii (Looijenga 2003:84), to a male name (Williams 1998:602; Düwel 2004:139, 2008:24; Roost 2021:159), or, as mentioned above, may mean “army.” Antonsen (1975:32) translates harja as “warrior,” noting cognates such as Gothic harjis and Old Icelandic herr. In Kroonen (2013:211), Proto-Germanic *harja is identical to the runic inscription, meaning “host, troop, army.” Kroonen (2013:212) and Antonsen (1975:32) note that one of Óðinn’s names is Herjann, which is unlikely to be a coincidence. Nevertheless, harja seems to refer to a person’s name.

This line in “In Maidjan” therefore means “I am called Harja.”

Rune names

“In Maidjan” names the runes in lines 8-11, using the names given to the 24 runes in the elder futhark. Rune names are known from the 10th century English, 13th century Norwegian and 14th century Icelandic rune poems (Looijenga 2003:6; Griffiths 2013:104; Benoist 2018:10). Manuscripts such as the Codex Leidensis and the Abecedarium Nordmannicum date no earlier than the 9th century, and therefore contain only the names of the 16 runes in the younger futhark (Looijenga 2003:6; Düwel 2008:190; Symons 2016:165; Benoist 2018:10). The late 8th-century Salzburg-Wiener-Alcuin manuscript describes the Anglo-Saxon futhorc with 28 runes and their names, as well as eight more runes from the elder futhark (Düwel 2008:191). Because of the significant time difference between the use of the runes of the elder futhark and the recording of their names in manuscripts, original names have been reconstructed with the help of the names in the Anglo-Saxon futhorc (Knirk 2002:636; Looijenga 2003:6; Benoist 2018:10). Unlike the runic inscriptions themselves, the names of the runes from the elder futhark therefore do not strictly date from the period, and many of these names are disputed (Düwel 2004:123). Poruciuc (2020:19-20) provides an etymological discussion of the names of the runes in the elder futhark, and their names can be found in Looijenga (2003:7) or Düwel (2004:123).

The names of the runes have been suggested to serve a mnemonic function, contain traces of traditional wisdom, or of cultic or divinatory practices (Symons 2016:158) (see also Knirk 2002:636). In any case, the runes are tied to prehistoric Germanic culture and religion, especially since the Hávamál (verse 138-139) claims that Óðinn sacrificed himself to obtain the runes (Pettit 2023:112-113):

| Veit ek at ek hekk vindga meiði á

nætr allar níu, geiri undaðr ok gefinn Óðni, sjálfr sjálfum mér, á þeim meiði er mangi veit hvers hann af rótum renn.

Við hleifi mik sældu né við hornigi, nýsta ek niðr, nam ek upp rúnar, œpandi nam; fell ek aptr þaðan.

|

I know that I hung on a windy tree

for all of nine nights, wounded by a spear and given to Óðinn, myself to myself, on that tree of which no one knows the kind of roots it runs from.

They blessed me with neither bread nor horn, I peered down, I took up runes, screaming I took them; I fell back from there. |

The lines in “In Maidjan” that recite the names of the runes may be interpreted as an attempt to establish or reestablish a connection with Germanic tradition, given the religious significance of the runes.

Wuotani Ruoperath

To my knowledge, line 12 of “In Maidjan” is not found amongst the runic inscriptions of the elder futhark, and all online mentions of either Wuotani or Ruoperath refer to the lyrics of “In Maidjan” (with the exception of a t-shirt, but that may be as a result of Heilung’s influence).

Wuotan is the Old High German form of Óðinn (Orel 2003:469), from Proto-Indo-European *uāt (“to be furious”) (Gimbutas 1999:227; Pokorny 2007:3227). Vikernes (2000:21) calls this “Det gamle germanske navnet på Óðinn,” but Orel (2003:469) and Düwel, Nedoma and Oehrl (2020:465) provide the earliest form of Óðinn as *wōđanaz. The word is cognate with Proto-Germanic wōda (“delirious”) (Pokorny 2007:3227; Kroonen 2013:592). Interestingly, this word is also cognate with Old Norse óðr (“mind, feeling; song, poetry”) and Old English wōð (“sound, noise; voice, song”) (Pokorny 2007:3227; Kroonen 2013:592). The suffix denotes “ruler of” (Green 1998:124; Düwel, Nedoma and Oehrl 2020:465), which means the name Óðinn can be translated as “ruler of the frenzy” or “ruler of the mind/poetry” (see also Düwel 2004:134), or as Düwel, Nedoma and Oehrl (2020:466) translate the name, “die Überordnung über den Bereich der (dichterischen und prophetischen) Inspiration bzw. Weisheit.”

Ruopen means “to call out” in Old Low Franconian, whereas Old High German uses the form ruofan (Robinson 2004:182). The Proto-Germanic form is *hrōpan (Kroonen 2013:249).

Line 12 clearly combines Óðinn with “to call out,” but interestingly, it combines Old High German with Old Low Franconian.

Gleiaugiz Eiurzi

This line refers to the Nebenstedt I B-Bracteate, found in Nebenstedt, Germany (Looijenga 2003:211), and dated to 450 – 550 CE (Antonsen 1975:62; Roost 2021:161). The text reads, glïaugizu ïurnzl, using the elder futhark (Looijenga 2003:211; Düwel 2008:47).

Looijenga (2003:211) translates glïaugiz as “One with a gleaming eye,” from glì (“to glow”) and augiz (“eyed”) (see also Krause 1971:156, Düwel 2008:47 and Düwel, Nedoma and Oehrl 2020:517). Antonsen (1975:62) translates this word as “bright-eyed,” while Düwel (2008:47) reminds that Óðinn is also known as Báleygr, “the one with the flaming eye.” Hauck (1998:344) also notes that glïaugiz may be a reference to Óðinn. Uïu (from the root *wì(h)ju) may be translated as “I consecrate”, and rnz probably stands for r[u]n[o]z (rùnòz), “the runes,” with an additional l (laukaz) at the end (Hauck 1998:307; Looijenga 2003:212; Düwel 2008:47; Düwel, Nedoma and Oehrl 2020:517). The whole inscription may then be translated as, “One with a gleaming eye consecrates the runes, l(aukaz)” (Hauck 1998:307; Looijenga 2003:212; Düwel 2008:47), or “Ich der Glanzäugige ( = der Runenmeister mit dem scharfen, magisch wirkenden Blick) weihe die Runen” (Krause 1971:156).

Line 13 therefore means, “The one with a gleaming eye (Óðinn) consecrates the runes.”

Au Is Urki

Au is urki forms part of the inscription on the Eggja stone in Norway, which is the longest inscription in the elder futhark ever found (Looijenga 2003:341). While the stone has been suggested to date from the 7th century, this has not been determined with certainty (Krause 1971:143; Looijenga 2003:342). If the dating is correct, it would mean that this is one of the youngest inscriptions in the elder futhark ever found, since the elder futhark was replaced with the younger around this time.

The text is thought to allude to a fertility rite, though there are other possibilities as well, like an unidentified burial custom, a violent sacrifice, a mythological background about which no information has been passed down, and a formulaic warning against disturbing the grave (Looijenga 2003:341). Düwel (2008:42) also notes that the inscription remains a mystery. The section of the Eggja stone quoted in “In Maidjan” reads, Alu misurki (Krause 1971:143; Looijenga 2003:342). Looijenga (2003:342) translates the phrase as, “Alu criminal”, while Krause (1971:143) translates it as, “Zauber dem Missetäter.” As noted earlier, alu is a magical word of which the meaning is uncertain, but it occurs often in runic inscriptions in the elder futhark and usually in a magical context.

Line 14 of “In Maidjan” is therefore difficult to interpret, except that it has something to do with a criminal and a magical statement.

Uiniz Ik

This line refers to the Sønder Rind-B bracteate found in Jutland, Denmark, which dates to between the mid 5th and mid 6th centuries (Looijenga 2003:217; Roost 2021:183). The text reads, iwinizik, composed of winiz (“friend”) and ik (“I”), hence the inscription can be translated as, “Friend am I” (Looijenga 2003:217; Düwel 2008:49; Roost 2021:183). Düwel (2008:49) adds that the bracteate depicts Óðinn, and therefore interprets the inscription as a divine statement that the wearer of the bracteate will be protected.

The last line of “In Maidjan” is therefore also unambiguous, “Friend am I.”

Discussion

The lyrics of “In Maidjan” are a collection of some of the oldest runic inscriptions, mostly – with the exception of the opening “Harigasti teiwa” and “Wuotani Ruperath” – written in the elder futhark. Table 1 provides an overview of the texts used, and it can be seen here that seven different runic inscriptions in the elder futhark were used. If a text was dated between two dates, I indicated the middle date and used this middle date to calculate the average date of texts. The names of the runes were not used in this calculation, because these were reconstructed afterwards since there are no texts from the period available to provide the names of the runes in the elder futhark. As can be seen in Table 1, the texts used in “In Maidjan” have an average date of 350 CE.

Table. 1. A summary of runic inscriptions used in “In Maidjan.”

| Number | Line | Original inscription | Find | Country | Date CE | Script |

| 1 | Harigasti Teiwa | hariχastiteiwa | Negau helmet B | Slovenia | -150 | Etruscan |

| 2 | Tawol Athodu | tawo l | aþodu | Trollhättan A-Bracteate | Sweden | 500 | elder |

| 3 | Ek Erilaz | ek erilaʀ | Lindholmen Amulet | Sweden | 450 | elder |

| 4 | Owlthuthewaz | owlþuþewaz | Thorsberg I sword chape | Germany | 200 | elder |

| 5 | Niwaremariz | niwajemariz | Thorsberg I sword chape | Germany | 200 | elder |

| 6 | Saawilagar | Sa(wil)agaʀ | Lindholmen Amulet | Sweden | 450 | elder |

| 7 | Hateka Harja | ha[i]teka Harja | Vimose Comb | Denmark | 150 | elder |

| 8 | Fehu Uruz Thurisaz Ansuz Raidho Kenaz | elder | ||||

| 9 | Gebo Wunjo Hagal Naudhiz Isa Jera | elder | ||||

| 10 | Eihwaz Perthro Algiz Sowelu Tiwaz Berkano | elder | ||||

| 11 | Ehwaz Mannaz Laguz Ingwaz Dagaz Othala | elder | ||||

| 12 | Wuotani Ruoperath | |||||

| 13 | Gleiaugiz Eiurzi | glïaugizu ïurnzl | Nebenstedt I B-Bracteate | Germany | 500 | elder |

| 14 | Au Is Urki | Alu misurki | Eggja stone | Norway | 700 | elder |

| 15 | Uiniz Ik | iwinizik | Sønder Rind-B bracteate | Denmark | 500 | elder |

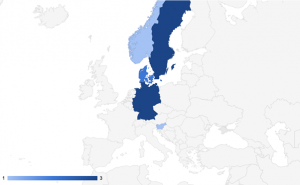

Table 1 also indicates that texts were discovered in five different countries. Figure 1 shows where inscriptions were found that were used in “In Maidjan.” As can be seen in this figure, these countries are at the heart of the pre-Christian Germanic world.

In terms of the content of inscriptions used in “In Maidjan,” the meaning of many texts — such as the Negau helmet B and the Thorsberg I sword chape — are uncertain, with scholars still debating the exact meaning of these inscriptions. Heilung’s attitude of leaving the inscriptions untranslated therefore is not only academically responsible, but also allows the reader to infer which interpretation is best suited. This pattern of uncertainty and open interpretation aligns with Heilung’s intention to create a space for dialogue and exploration of ancient Germanic traditions.

There is also a clear emphasis on the magical: the texts from the Trollhättan A-Bracteate, the Lindholmen Amulet, the Eggja stone, and the Nebenstedt I B-Bracteate all have clear magical connotations, while the Negau helmet B, the Thorsberg I sword chape and the Sønder Rind-B bracteate may have magical connotations. The new context of these runic inscriptions with uncertain interpretations as part of one song however favour the magical interpretations. This emphasis on magic reflects the mystical and spiritual nature of Heilung’s music and their aim to revive ancient Germanic traditions in a contemporary context, a fact supported by their ritualistic live performances (see Fitzgerald 2023). Note also that numerous lines of the song (“Harigasti Teiwa!”, “Hateka Harja”, “Wuotani Ruoperath”, “Gleiaugiz Eiurzi”, and “Uiniz Ik”) either directly or indirectly, certainly or possibly refer to Óðinn, thus confirming the primacy of Óðinn amongst the Germanic gods and particularly in the context of Norse magic and spiritualism. Fitzgerald (2023:149) also recalls how Heilung performed a ritual dedicated to Óðinn during their performance at Midgardsblot in 2022.

Apart from including the oldest Germanic text ever found (Negau helmet B), “In Maidjan” also includes the oldest runic inscription found to date, the Vimose Comb. This further cements the song as particularly old, since the song includes not only the oldest Germanic text, but also the oldest text written in the Germanic script, the runes.

In addition, the use of the oldest runic inscription in the elder futhark is contrasted by including one of the youngest inscriptions in the elder futhark, the Eggja stone. These two inclusions bracket the use of the elder futhark, which is usually dated to around 50-700 CE (Looijenga 2020:820; Roost 2021:8).

One outlier in the study is the line “Wuotani Ruoperath,” which does not seem to correspond to any known runic inscription. This suggests that Heilung may have created this line specifically for the song, perhaps as a way to invoke the spirit of Óðinn. While this deviation from using existing inscriptions may be seen as a departure from the historical accuracy of the other lines, it aligns with Heilung’s artistic vision and their desire to create a unique and immersive experience for their listeners.

It is clear from the above that Heilung made a detailed study of the runic inscriptions in the elder futhark for “In Maidjan.” The song references some of the most important finds and combines them into a song whose meaning cannot be pinned down with certainty, but which may be summed up as a magical invocation.

The current study did not consider the musical and performance aspects of “In Maidjan.” While the focus of this research was on the origins and meanings of the lyrics, a more comprehensive analysis could have explored how the music and performance style contribute to the overall message and atmosphere of the song. Future research could delve into the musical composition, vocal techniques, and stage presence of Heilung to gain a more holistic understanding of their artistic expression.

Conclusion

The analysis of Heilung’s song “In Maidjan” reveals the use of some of the oldest runic inscriptions, predominantly from the elder futhark, to create a mystical and authentic connection with Germanic traditions. The inclusion of these inscriptions, along with the emphasis on magical elements and the invocation of Óðinn, adds a sense of authenticity to the song’s lyrics. While there are some outliers and uncertainties in the interpretation of the inscriptions, Heilung’s approach of leaving these open to discussion encourages further exploration. Future research could expand on this study by examining the musical and performance aspects of Heilung’s music and exploring the broader cultural and historical context of the runic inscriptions used in their songs.

Bibliography

Antonsen, E. H. 1975. A concise grammar of the older runic inscriptions. Tübingen: Max Niemeyer Verlag.

Arntzen, A. F. 2023. Odin rir metallen. En religionsvitenskapelig undersøkelse av bruk av symboler og elementerfra norrøn religion i norsk svartmetall. Master thesis. Universitet i Oslo.

Benoist, A. D. 2018. Runes and the origins of writing. London: Arktos Media.

Düwel, K., Nedoma, R. and Oehrl, S. 2020. Die südgermanischen Runeninschriften (Ergänzungsbände zum Reallexikon der Germanischen Altertumskunde 119). Boston: De Gruyter.

Düwel, K. (ed.) 1998. Runeninschriften als Quellen interdisziplinärer Forschung. Berlin: Walter de Gruyter.

Düwel, K. 2004. Runic, in Murdoch, B. and Read, M. (eds.) Early Germanic Literature and Culture. Rochester: Camden House, 121–148.

Düwel, K. 2008. Runenkunde. Stuttgart: Springer-Verlag.

Fitzgerald, P. and Nordvig, M. 2023. Spellbinding Skalds: Music as Ritual in Nordic Neopaganism, in Borkataky-Varma, S. and Ullrey, A. M. (eds.) Living Folk Religions. London: Routledge, 191–203.

Fitzgerald, P. M. 2023. Til Valhall: The formation of Nordic Neopagan identity, religiosity, and community at a Norwegian heavy metal festival. Doctoral dissertation. University of Denver.

Gimbutas, M. A. 1999. The Living Goddesses. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Green, D. H. 1998. Language and History in the Early Germanic World. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Griffiths, A. 2013. A family of names: Rune-names and Ogam-names and their relation to alphabet letter-names. Doctoral dissertation. Leiden University.

Hansen, B. S. S. and Kroonen, G. J. 2022. Germanic, in Olander, T. (ed.) The Indo-European language family. A Phylogenetic perspective. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Hauck, K. 1998. Zur religionsgeschichtlichen Auswertung von Bildchiffren und Runen der völkerwanderungszeitlichen Goldbrakteaten (Zur Ikonologie der Goldbrakteaten, LVI), in Runeninschriften als Quellen interdisziplinärer Forschung. Berlin: Walter de Gruyter, 298–356.

Hultgård, A. 1998. Runeninschriften und Runendenkmäler als Quellen der Religionsgeschichte, in Düwel, K. (ed.) Runeninschriften als Quellen interdisziplinärer Forschung. Berlin: Walter de Gruyter, 715–737.

Knirk, J. E. 2002. Runes: Origin, development of the futhark, functions, applications, and methodological considerations, in Bandle, O., Braunmüller, K., Jahr, E. H., Karker, A., Naumann, H.-P., and Teleman, U. (eds.) The Nordic Languages. An International Handbook of the History of the North Germanic Languages. Berlin: Walter de Gruyter, 634–648.

Krause, W. 1971. Die Sprache der urnordischen Runeninschriften. Heidelberg: Carl Winter.

Kretschmer, P. 1929. Das älteste germanische sprachdenkmal, Zeitschrift für deutsches Altertum und deutsche Literatur, 66(1):1–14.

Kroonen, G. 2013. Etymological Dictionary of Proto-Germanic. Leiden: BRILL.

Looijenga, T. 2003. Texts & contexts of the oldest runic inscriptions. Leiden: Brill Academic Publishers.

Looijenga, T. 2020. Germanic: Runes, Prace Historyczne, (20):819–853. doi: 10.36707/palaeohispanica.v0i20.371.

Makaev, E. A. 1996. The language of the oldest runic inscriptions: A linguistic & historical philological analysis. Coronet Books Inc..

Mees, B. 1999. The Celts and the Origin of the Runic Script, Studia Neophilologica, 71:143–155.

Mees, B. 2012. The Meldorf fibula inscription and epigraphic typology, Beitraege zur Namenforschung, 47(3):26.

Mees, B. 2022. The English language before England: an epigraphic account. New York: Routledge. doi: 10.4324/9781003268321.

Orel, V. 2003. A handbook of Germanic etymology. Leiden: Brill.

Pettit, E. 2023. The Poetic Edda: A Dual-Language Edition. Cambridge, UK: Open Book Publishers. doi: 10.11647/OBP.0308.

Pokorny, J. 2007. Indogermanisches Etymologisches Wörterbuch. Unknown: Indo-European Language Revival Association.

Poruciuc, A. 2020. The peculiar position of germanic runes in the history of script, Linguaculture, 11(2):13–26. doi: 10.47743/lincu-2020-2-0169.

Price, T. D. 2015. Ancient Scandinavia: An archaeological history from the first humans to the Vikings. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Reichardt, K. 1953. The inscription on Helmet B of Negau, Language, 29(3):306–316.

Robinson, O. W. 2004. Old English and its closest relatives. London: Routledge.

Roe, S. 2019. Against the Modern World: NeoFolk and the Authentic Ritual Experience, Literature & Aesthetics, 29(2):15–31.

Roost, J. 2021. Elliptical Epigraphy–What text types and formulas can tell us about the purpose of Gallo-Latin and Elder Futhark inscriptions. Doctoral dissertation. Universität Basel.

Sanders, R. 2010. German: Biography of a language. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Senekal, B. A. 2021. Ou wyn in nuwe sakke: Die onlangse herlewing van die Germaanse kultuur op Instagram, LitNet Akademies Geesteswetenskappe, 18(2):132–160.

Symons, V. 2016. Runes and Roman Letters in Anglo-Saxon Manuscripts. Berlin: De Gruyter.

Szőke, V. 2018. The Norwegian Rune Poem in context: structure, style and imagery, l’Analisi Linguistica e Letteraria, 5–32.

Trafford, S. 2021. Nata vimpi curmi da: Dead languages and primordial nationalisms in folk metal music, in Valijärvi, R.-L., Doesburg, C., and Digioia, A. (eds.) Multilingual metal music: Sociocultural, linguistic and literary perspectives on heavy metal lyrics. Bingley: Emerald Publishing Limited, 223–240. doi: 10.1108/978-1-83909-948-920200020.

Vikernes, V. 2000. Germansk Mytologi Og Verdensanskuelse. Unknown: Cymophane Publishing.

Williams, H. 1998. Runic Inscriptions as sources of personal names,” in Düwel, K. (ed.) Runeninschriften als Quellen interdisziplinärer Forschung. Berlin: Walter de Gruyter, 601–610.

[1] This line is omitted in https://www.musixmatch.com/lyrics/Heilung/In-Maidjan, but can clearly be heard in the song itself.