Dr. Burgert Senekal, University of the Free State

Ensovoort, volume 45 (2024), number 09: 1

Abstract

This study examines the Norse Pagan revival in music, focusing on the Norwegian musical project Wardruna and its network on the streaming platform Spotify. The aim of this study is to provide a comprehensive view of the environment surrounding Wardruna’s music on Spotify, exploring the network of artists and genres associated with this artist. To achieve this, a network analysis is employed, utilising data from Spotify’s API to construct and analyse the network of connections between Wardruna and other related artists. The analysis includes clustering and modularity to identify key nodes and communities within the network. Additionally, the study investigates the genres most closely associated with the Norse Pagan revival, uncovering their interconnections within the network. The findings of this study reveal the intricate web of relationships within the Norse Pagan revival music scene on Spotify. The analysis also highlights the presence of distinct communities and clusters, indicating the existence of subgenres within the broader movement.

Keywords: black metal, dark Nordic folk, Heathen, Heilung, network analysis, Midgardsblot, Norse Pagan, Pagan, Spotify, Wardruna.

Introduction

The resurgence of interest in Norse Paganism, also known as Nordic Neo-Paganism, has been observed in various cultural expressions, including music. This revival encompasses the rekindling of folk beliefs and traditions derived from the Scandinavian and Germanic cultural areas in Northern Europe (Fitzgerald and Nordvig 2023:191). One prominent example of this revival in music is the Norwegian musical project Wardruna, which has gained significant attention for its evocative and authentic exploration of Norse spiritual and cultural themes.

The current study conducts a network analysis of Wardruna’s environment on the music streaming platform Spotify. By examining the network of artists and genres connected to Wardruna within the digital music ecosystem, this research seeks to understand the interconnectedness of Wardruna with other artists and genres on Spotify.

The article begins by providing an overview of the resurgence of Norse Paganism in music, with a focus on the Norwegian musical project Wardruna, as well as the multinational Heilung. The article then outlines the methods used, including how data was gathered and the network measures used. This is followed by a presentation and discussion of the results. The article concludes with summary remarks and suggestions for further research.

Dark Nordic Folk

Background

Modern NeoFolk bands have their origins in mainly two music scenes: NeoFolk in Britain in the 1980s, and the Norwegian black metal scene of the 1990s (Granholm 2011; Roe 2019). The term NeoFolk was first used to describe bands such as Death in June, Current 93, and Sol Invictus that developed out of the British industrial movement in the 1980s and involved a rejection of modernity (Granholm 2011:532; Roe 2019:16). In the mid-1980s, members of these bands such as Douglas Pearce (Death in June), Tony Wakeford (Sol Invictus), David Tibet (Current 93), and Ian Read (first from Sol Invictus and later Fire + Ice) met in the London house of the rune occultist, Freya Aswynn, and they were also involved with numerous Pagan organisations and publications (Von Schnurbein 2016:342). Ian Read also worked with Current 93, Death in June, and Sol Invictus from the mid 1980s (Granholm 2011:533).

In Norway, part of the Norwegian black metal scene moved away from earlier Satanic anti-Christian sentiments to more pro-Pagan anti-Christian sentiments by the early 1990s (Roe 2019:16). This scene incorporated Norse themes and imagery such as the runes (Roe 2019:17). To Granholm (2011:529), this development is consistent with earlier attitudes, and even the earlier Satanic sentiments should be seen as Pagan, “early Norwegian Black Metal should be characterized as ‘pagan’ or ‘heathen,’ since labeling it as ‘satanic’ does not sufficiently describe the particularities of it.” Bathory was a pioneer group in this genre, who were already using Norse mythology in their lyrics by 1988 (Kahn-Harris 2007:105; Von Schnurbein 2016:337; Peters 2020:136). Roleplayers in the Norwegian black metal scene were also involved in establishing Norse Pagan religious organisations, such as Varg (Kristian) Vikernes of the Norwegian group, Burzum, who founded the Norwegian Heathen Front (Norsk Hedensk Front) in 1993 (Gunstad 2015:28; Von Schnurbein 2016:337). Kahn-Harris (2007:40) writes about black metal’s Norse Pagan sentiments,

Scandinavian black metal bands often invoke the Vikings and mourn the arrival of Christianity in the Middle Ages, almost claiming themselves to be colonized people. Pagan society is constructed as lacking the ‘weakness’ that characterizes contemporary society (see also Unger 2016:80).

Metal bands – not all of them black metal – that include Norse/Germanic mythology in their lyrics include Bathory, Tyr, Finntroll, Ultima Thule, Helheim, Solefald, Menhir, Therion, Sturmgeist, Amon Amarth, Moonsorrow, Unleashed, Sabaton, Enslaved, Skyclad, Riger, Einherjer, Amorphis and Bifrost (Senekal 2021:140). Metal’s ties with Norse content are however extensive, and Peters (2020) even discusses earlier Norse content in the lyrics of bands such as Led Zeppelin, Motörhead, Jethro Tull and Manowar.

The 1994 release of the first complete album of the Norwegian band, Enslaved, Vikingligr Veldi, introduced the idea of using ancient languages into the folk metal discourse (Trafford 2021:228). Trafford (2021:229) calls this album “one of the foundational statements of Viking Metal: it helped to establish a blueprint for the genre as a whole, and also for folk metal as that emerged in the 1990s and later.” In the future, various bands would follow their example and incorporate lyrics in Old Norse, Proto-Germanic and Gaulish. This use of ancient languages also ties in with the trend in extreme metal in the 1990s to move away from English lyrics. Extreme metal bands were starting to use local languages more often in their lyrics to express their resistance to and distancing from the neo-liberal Anglo-American hegemony that was rapidly becoming a world culture (Trafford 2021:229).

From these folk and black metal traditions, a new type of folk music developed. Fitzgerald and Nordvig (2023:192) refer to Dark Nordic Folk, which “emerged at the intersection of extreme metal and Nordic folk music, and is characterized by its foreboding and energizing sound”. As such, Fitzgerald and Nordvig (2023:192) call Dark Nordic Folk bands such as Wardruna and Heilung “adjacent to heavy metal subculture.” Similarly, Granholm (2011:515) argues,

These two scenes [Black Metal and Neofolk] have in recent years drawn closer to each other, to the degree that we can even speak of a partial convergence – a particularly interesting development as these two musical genres would seem to have little in common. […] My thesis is that this development is possible due to the presence of heathenism as a key element in the “complex cultural system” of Black Metal and Neofolk.

Wardruna and Heilung are often seen as representative of this new music scene and most studies of modern NeoFolk or Dark Nordic Folk emphasise Wardruna and Heilung (Roe 2019; Arntzen 2023; Fitzgerald 2023; Fitzgerald and Nordvig 2023). Fitzgerald and Nordvig (2023:191) for instance remark, “In the music scene attached to Nordic Neopaganism, two musical groups are prominently featured: Heilung and Wardruna.” Fitzgerald (2023:42) also writes,

These bands are not only considered authoritative for their self-narration and sharing of their ritual creative processes, they are noteworthy authority figures for their proliferation of a popular element of Nordic Neopagan lore, music and melody heavy with symbolism gleaned from an idealized Nordic past, performed by the bands simultaneously as a self-reflexive exploration of their own spiritual selves and as an art form that can be engaged by adherents of Nordic Neopaganism in their day to day and spiritual lives. The popularity of their music among Nordic Neopagan aligned listeners has opened the door for the establishment of an alternative sacred space that adherents can make pilgrimage to: the music festival.

Importantly, most of the performers in these bands and many of their followers identify as Norse Pagan (Fitzgerald 2023:1; Fitzgerald and Nordvig 2023:192). Wardruna and Heilung are therefore more than simply artists; they become facilitators of Norse Pagan spiritual experiences. For these experiences, the music festival, Midgardsblot, held every year in Borre, Norway, is of particular importance. Starting in 2015, this festival has hosted artists such as Wardruna, Heilung, Enslaved, Dimmu Borgir, Nytt Land, Folket Bortafor Nordavinden and Glittertind. The festival is a collaborative project between the museum Midgard Vikingsenter, Horten municipality, Vestfold county council, the Cultural Council and the Swedish commercial company Grimfrost, which sells Viking and Norse related goods (Skjoldli and Gregorius 2023:107). A variety of ritualizations take place in Midgardsblot, for instance the opening ceremony, which has been referred to as a blot since it was conducted there for the first time in 2015 (Skjoldli and Gregorius 2023:108). The transnational social dimension of Midgardsblot can be loosely characterised as a gathering point for at least three subcultures: Norse-oriented pagans, Viking enthusiasts, and black metal enthusiasts (Skjoldli and Gregorius 2023:108). Fitzgerald (2023:ii) remarks on the significance of Midgardsblot,

… Midgardsblot is a coalescence point of Nordic Neopagan material culture: constituent elements of the established body of lore such as music, the landscape, and Nordic folk cultural symbolism. Furthermore, respected figures and contributors to the body of lore such as scholar practitioners and certain performers are present, providing lectures on Nordic history, folk tradition, ritual practice, and the role of Nordic Neopaganism in social and climate justice. This coalescence of Nordic Neopagan material culture, the act of traveling to the festival, the academic discourse and ritual performances, and the sense of community experienced by those in attendance solidify Midgardsblot as a sacred space for practitioners to constitute and refine Nordic Neopagan identity and community.

Midgardsblot has become an annual meeting place for Norse Pagans (amongst others), and since the festival is primarily marketed as a music festival, music therefore takes centre stage. Furthermore, of the musicians that perform at Midgardsblot, Wardruna and Heilung are generally considered central. Both bands therefore play a role in Norse Paganism that reaches much further than simply musical performances. Because of the primacy of these two bands in the Dark Nordic Folk music scene and in Norse Paganism, the following sections discuss them in more detail.

Wardruna

Wardruna’s roots lie in Scandinavian black metal (Robb 2013; Roe 2019:18), and in fact the band was founded by former members of the black metal band, Gorgoroth (Granholm 2011:533; Arntzen 2023:69; Fitzgerald and Nordvig 2023:191). The group was founded in 2003 by Einar “Kvitrafn” Selvik, Kristian “Gaahl” Hella and Lindy-Fay Hella (Roe 2019:17; Fitzgerald and Nordvig 2023:191), all from Norway. Their acceptance into the metal music scene can be seen in the fact that they have already performed at metal music festivals such as Wacken Open Air in Germany and Brutal Assault in the Czech Republic (Roe 2019:30), although they also perform at historical reenactments and places of cultural significance, such as the Viking Ship Museum in Oslo (Roe 2019:19; Trafford 2021:225).

Wardruna means “the sound of the runes” (Robb 2013), and their lyrics are in modern Norwegian, Old Norse and proto-Norse, while their lyrics often reference Norse Mythology from texts such as the Poetic Edda, the Prose Edda and other skaldic poetry (Roe 2019:23). In contrast to metal bands, Wardruna does not utilise any distortion on guitars and only plays acoustic instruments, although Selvik’s vocal technique is akin to the distorted vocals of many Norwegian black metal artists (Roe 2019:18). Selvik claims that his distinctive vocal style evolved from the Tuvan form of throat-singing (Roe 2019:18).

Wardruna has been a highly visible Norse Pagan band in popular culture, and several of their songs were included in the soundtrack to the television series, Vikings, including “Helvegen” (Season 2 episode 8) (Senekal 2021:141; Trafford 2021:232). Einar Selvik also played a short role in this television series, sending off warriors in Season 4, Episode 6.

To date, Warduna has released six albums: Runaljod – Gap Var Ginnunga (2009), Runaljod – Yggdrasil (2013), Runaljod – Ragnarok (2016), Skald (2018), Kvitravn (2021), and Kvitravn – First Flight of the White Raven (live album, 2022).

Heilung

Heilung was founded in 2014 by Kai Uwe Faust and Christopher Juul, with Maria Franz joining in the following year (Roe 2019:19; Sommer 2020). The group has an international Germanic origin: Franz is from Norway, Juul from Denmark and Faust from Germany (Roe 2019:19). Like Wardruna, Heilung is usually discussed as a metal band (Roe 2019:18; Sommer 2020; Arntzen 2023:70). Sommer (2020) for instance argues, “Heilung access dark metal’s urgency and lock-jaw intensity without a single guitar in sight,” while Roe (2019:15) refers to Heilung’s occupation of a “liminal space,” “between pagan-inspired folk music and extreme metal.” Heilung differs from Wardruna in that they do not only focus on Old Norse content and they have performed alongside Native American bands (Roe 2019:26; Fitzgerald 2023:71), and while Wardruna draw inspiration mainly from Old Norse poetry, Heilung often draws inspiration from runic inscriptions (Roe 2019:25).

Heilung attempts to reconstruct a pre-Christian past on stage, with ritual wardrobes, actors and by performing rituals. As argued by Fitzgerald and Nordvig (2023:196),

They evoke themselves as ancient Nordic seers and warriors. Their ritualized creative process, utilization of historically accurate instrumentation, and composed lyrics in both Old Norse and Proto-Germanic transport the audience to a liminal space in which another time is brought to the present.

Like Wardruna, Heilung has also been visible in popular culture, and Heilung contributed two songs to the television series, Vikings, namely “Alfadhirhaiti” and “In Maidjan.” Heilung also composed the soundtrack for the computer game, Senua’s Saga: Hellblade II (Senekal 2021:140).

To date, Heilung has released four albums: Ofnir (2015/2018), Lifa (2018), Futha (2019), and Drif (2022).

Although frequently highlighted, the current NeoFolk or Dark Nordic Folk music scene is much broader than simply Wardruna and Heilung, and also includes bands such as Danheim, SKÁLD, Nytt Land and others. Furthermore, as noted earlier, Dark Nordic Folk also ties in with other genres such as black metal. It is this broader scene that is investigated in the current study. The following section discusses the methods employed in the current study.

Methods

Data gathering

In order to investigate the Dark Nordic Folk music scene and its surroundings, a network of related artists was studied using data from Spotify. Data was scraped from Spotify on 3 January 2024 using the Spotify Artist Network scraper tool (Rieder 2023). Spotify was chosen because this music sharing platform is one of the most popular services of its kind globally, and it provides access to one of the highest number of artists of all online music streaming platforms (Fumić, Rumac and Orehovački 2023). Using machine learning and the user playlists of over 850 million users, Spotify has developed an algorithm that calculates which artists are related based on their co-occurrences on users’ playlists (Anderson et al. 2020:3-4). This algorithm is described in Anderson et al. (2020).

The tool by Rieder (2023) queries Spotify’s Application Programming Interface (API) based on a search for an artist, and collects artists that Spotify’s algorithm has classified as “related artists”, to the second degree (i.e. artists related to artists that are related to the artist that was searched for). The genres allocated to the artist are also collected, and note that an artist can have numerous genres associated with him/her/them. Spotify internally assigns genres by having data curators identify groups of artists using a machine-assisted method that considers cultural knowledge, acoustic qualities, and aggregate listening (Anderson et al. 2020:3).

It was decided to focus on the network of artists related to Wardruna, because this network includes artists such as Heilung, and Wardruna is more popular than Heilung on Spotify. Wardruna has a Spotify popularity score of 55 with 635,069 followers, compared with Heilung’s popularity score of 54 with 500,765 followers (as on 3 January 2024). Their respective popularity on Spotify echoes their popularity on Instagram, with Wardruna and Heilung for instance having 303,000 and 253,000 followers respectively on Instagram (as on 3 January 2024). In addition, while Trafford (2021) writes extensively about Wardruna, he does not mention Heilung, which underscores Wardruna’s eminence in this genre. Experiments also showed that there is a large amount of overlap between the networks of related artists of these two bands.

Table 1 provides an overview of the dataset. It can be seen here that 521 artists are included, with 309 genre labels associated with them. These artists also have a high number of followers, close to 17 million in total, although followers will overlap and followers therefore do not give an indication about the number of unique Spotify users that follow these artists.

Table 1. An overview of the dataset.

| Variable | Value |

| Number of artists | 521 |

| Total number of followers | 16881347 |

| Number of genres | 309 |

Data analysis

The Spotify Artist Network scraper tool (Rieder 2023) allows export in the .gdf (Graph Data Format) file format, which can further be analysed as a network using the network analysis software package, Gephi (Bastian, Heymann and Jacomy 2009). In such a network, artists are nodes and an edge is indicated when artists are classified as “related”, i.e. co-occurring on users’ playlists.

I was primarily interested in identifying groups of nodes (artists) that often co-occur in this network, since this identification will show which artists are most related to Wardruna, as well as which other music styles are closely related to this band. For this purpose, the modularity algorithm by Blondel et al. (2008) is well suited. Blondel et al.’s (2008) algorithm identifies communities of nodes where there are more edges between nodes in the community than between nodes in the community and those outside the community. More precisely, this method compares the number of edges that occur between nodes with the number of edges that would be expected if edge formation occurred randomly (Blondel et al. 2008:2). The result is that communities of nodes are clustered together when they co-occur often, and these communities are then assigned an arbitrary number for reference purposes. This algorithm is described in Blondel et al. (2008).

For data visualisation purposes, the force-based graph layout algorithm developed by Martin et al. (2011) was chosen because of this algorithm’s ability to identify communities in networks. While other force-based graph layout algorithms such as those by Fruchterman and Reingold (1991) and Hu (2012) tend to position the most important nodes in the centre of the graph, the fact that data was scraped outwards from the band Wardruna would mean that Wardruna would be positioned in the centre, which does not provide any new information. The algorithm by Martin et al. (2011) clusters nodes together that often co-occur, allowing for a straightforward visualisation of communities identified using Blondel et al.’s (2008) algorithm. It should be noted, however, that Blondel et al.’s (2008) algorithm and Martin et al.’s (2011) layout algorithm will overlap in the communities they identify, but these communities will not be identical. The algorithm by Hu (2012) was used to visualise connections in subsections of this network.

It was also considered necessary to identify the most important artists in every community, since these artists can provide an indication about which types of artists are found in the community. While network science has numerous centrality measures available to calculate a node’s importance, such as degree-, betweenness-, and closeness centrality, Spotify provides a popularity score and the number of followers, and these were considered ideal for the current study. Because the number of followers is a clearer metric than a popularity score, the number of followers was used below to highlight the most important artists in every community.

The following section discusses the results of the analysis.

Results

I first determined which music genres occur most often in the dataset. Table 2 shows the most popular music genres associated with artists that are related to Wardruna. It can be seen here that while these artists are mostly associated with various forms of folk, in particular mediaeval, nordic and viking folk, artists associated with Wardruna are also associated with rock and metal, and in particular black metal. These genre associations on Spotify echo what previous scholars have noted about Wardruna’s liminal position between folk and metal, and their close association with black metal (Granholm 2011; Roe 2019; Trafford 2021; Fitzgerald 2023; Fitzgerald and Nordvig 2023).

Table 2. The most popular music genres associated with Wardruna

| Genre | Count |

| mediaeval folk | 85 |

| neoclassical darkwave | 73 |

| neofolk | 63 |

| rune folk | 63 |

| viking folk | 54 |

| mediaeval rock | 51 |

| nordic folk | 50 |

| voidgaze | 42 |

| atmospheric black metal | 40 |

| ethereal wave | 37 |

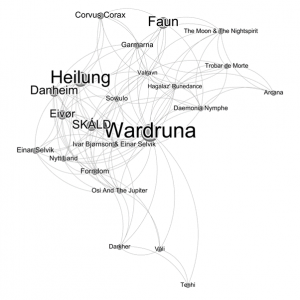

The network of artists related to Wardruna to the second degree consists of 521 nodes (artists) and 4881 edges (relatedness). If only Wardruna’s first degree links are considered, i.e. artists that Wardruna is directly related to, the network consists of 23 nodes and 124 edges. This first degree network is shown in Figure 1, where nodes are sized based on their number of followers, and the layout algorithm by Hu (2012) was used for the visualisation. It can be seen here that Heilung forms part of Wardruna’s direct connections, along with bands such as Faun, Danheim, SKÁLD, Eivør, Sowulo, and Nytt Land. This graph provides one way of showing which artists are most related to Wardruna, while modularity (discussed below) provides another.

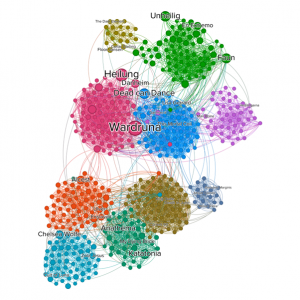

The modularity algorithm developed by Blondel et al. (2008) divided the network that includes second degree edges into 10 communities. Figure 2 shows the network of artists related to Wardruna on Spotify to the second degree. This network was visualised using the force-based layout algorithm developed by Martin et al. (2011). Nodes are coloured by their community, nodes are sized by their number of followers on Spotify, and labels are only indicated for the three artists in each community with the highest number of followers.

Figure 2 shows that Wardruna belongs to Community 2 (pink), along with Heilung and Danheim. The communities positioned closest to Community 2 are Community 5 (blue, represented by Dead Can Dance), Community 4 (green, represented by Unheilig), Community 7 (light brown, represented by Floor Jansen), Community 1 (orange, represented by Alcest), and Community 3 (brown, represented by Death In June). Their positioning close to Community 2 shows that these are also more similar to Wardruna than communities positioned further away. These communities are discussed in more detail below. Note that some artists were grouped together differently by the algorithms by Blondel et al. (2008) and Martin et al. (2011), with a light blue node and an orange node in the brown cluster, a pink node in the blue cluster, a dark green node in the orange cluster, two purple nodes in the blue cluster, and a green node in the blue cluster. In the discussion below, I follow the clustering determined by Blondel et al.’s (2008) algorithm.

Community 2 is the largest community and consists of 15.36% of nodes, followed by Community 4 (13.24% of nodes), Community 5 (12.48% of nodes), Community 3 (12.28% of nodes), Community 1 (12.09% of nodes), Community 8 (10.75% of nodes), Community 6 (9.02% of nodes), Community 9 (7.49% of nodes), and Community 7 (3.84% of nodes). These communities are discussed below in order of size, and the artists with the highest number of followers in each community are highlighted.

The nodes in Community 2 include Wardruna, Heilung, Danheim, SKÁLD, Eivør, Myrkur, Kalandra, Forndom, Einar Selvik and Ivar Bjørnson & Einar Selvik. This community therefore consists of the artists that are most similar to Wardruna, and includes solo projects and collaborations by Einar Selvik. Ivar Bjørnson is of the band Enslaved, and this collaboration therefore constitutes a direct link between Wardruna and black metal. This community also includes artists such as Nytt Land, Heldom and Kati Ran, the latter of which has also worked with Heilung. The five main genres associated with this community are viking folk, rune folk, mediaeval folk, nordic folk, and dark folk.

The nodes in Community 4 include Unheilig, Faun, In Extremo, Saltatio Mortis, Megaherz, Schandmaul, J.B.O., Blackmore’s Night, Feuerschwanz, and Van Canto. This community has a strong German association (although not limited to German bands), where Faun is for instance a particularly popular folk band, as seen in mentions on Instagram around the hashtag, #germanic (Senekal 2021:152). The five main genres associated with this community are mediaeval rock, mediaeval folk, neue deutsche harte, german metal, and german rock.

The nodes in Community 5 include Dead Can Dance, Lisa Gerrard, This Mortal Coil, Sopor Aeternus & The Ensemble Of Shadows, Nox Arcana, Deine Lakaien, Daemonia Nymphe, The Moon & The Nightspirit, Azam Ali and Brendan Perry. Lisa Gerrard and Brendan Perry were founding members of Dead Can Dance, and hence this community also includes their solo projects. The genres ascribed to this community most often are neoclassical darkwave, mediaeval folk, ethereal wave, rune folk, and dark wave.

The nodes in Community 3 include Death In June, King Dude, Current 93, Vàli, :Of The Wand And The Moon:, Tenhi, Spiritual Front, Ordo Rosarius Equilibrio, Darkwood, and Sol Invictus. This community includes some of the earlier British NeoFolk artists referred to earlier. While not one of the most popular bands, Fire + Ice also belongs to this community. As such, this community shows Wardruna being connected to earlier folk music traditions. The genres mentioned in this community are most often neofolk, martial industrial, neoclassical darkwave, dark folk, and rune folk.

The nodes in Community 1 include Alcest, Ulver, Enslaved, Agalloch, Sólstafir, Wolves in the Throne Room, Summoning, Harakiri for the Sky, Drudkh and Primordial. This is a strong black metal community, often with ties to the Scandinavian countries (e,g. Ulver, Enslaved and Sólstafir), and the genres associated most often with this community are atmospheric black metal, voidgaze, blackgaze, black metal, and post-black metal.

The nodes in Community 8 include Chelsea Wolfe, Zola Jesus, Cult Of Luna, Emma Ruth Rundle, Drab Majesty, The Soft Moon, Amenra, Brutus, Anna von Hausswolff, and Marissa Nadler. This community is associated with gaian doom, post-doom metal, post-metal, drone metal, and doomgaze.

The nodes in Community 6 include Garmarna, Mari Boine, Hedningarna, Ultra Bra, Värttinä, Väsen, Triakel, Hoven Droven, Frigg, and Annbjørg Lien. This community is associated with nordic folk, folkmusik, finnish folk, norwegian folk, and nyckelharpa.

The nodes in Community 9 include Katatonia, Anathema, My Dying Bride, Swallow The Sun, Draconian, Woods Of Ypres, Antimatter, Empyrium, Saturnus, and Lake Of Tears. This community is most often described as doom metal, Gothic metal, funeral doom, Finnish doom metal, and Swedish doom metal.

The nodes in Community 7 include Floor Jansen, Cellar Darling, The Dark Element, ReVamp, Dark Sarah, Leah, Lyriel, Auri, Marko Hietala, and Elvellon. This community is associated most often with symphonic metal, Gothic symphonic metal, fallen angel, Gothic metal, and hel.

The nodes in Community 10 include Atrium Carceri, Desiderii Marginis, Raison D’être, Kammarheit, Sephiroth, Treha Sektori, In Slaughter Natives, Nordvargr, Beyond Sensory Experience and Northaunt. This community is most often described as dark ambient, dronescape, neofolk, power electronics, and ambient industrial.

Table 3 summarises the preceding paragraphs, but also indicates the number of followers of the most popular band in each community, as well as the total number of followers per community. It can be seen here that while Community 2 consists of the highest number of bands, Community 4 – the German community – has the highest number of followers in total. Community 2 has the second highest number of followers, and the community with the third highest number of total followers is the black metal community, Community 1.

Table 3. Communities, popular bands, followers and genres.

| Community | Bands | Most popular band | Followers (artist) | Followers (Community) | Main genres |

| 2 | 80 | Wardruna | 635069 | 3083882 | viking folk, rune folk, medieval folk, nordic folk, dark folk |

| 4 | 69 | Unheilig | 362179 | 3804849 | medieval rock, medieval folk, neue deutsche harte, german metal, german rock |

| 5 | 65 | Dead Can Dance | 369318 | 1723171 | neoclassical darkwave, medieval folk, ethereal wave, rune folk, dark wave |

| 3 | 64 | Death In June | 76512 | 587502 | neofolk, martial industrial, neoclassical darkwave, dark folk, rune folk |

| 1 | 63 | Alcest | 253144 | 2593181 | atmospheric black metal, voidgaze, blackgaze, black metal, post-black metal |

| 8 | 56 | Chelsea Wolfe | 256832 | 2210846 | gaian doom, post-doom metal, post-metal, drone metal, doomgaze |

| 6 | 47 | Garmarna | 71009 | 259764 | nordic folk, folkmusik, finnish folk, norwegian folk, nyckelharpa |

| 9 | 39 | Katatonia | 331894 | 1922154 | doom metal, gothic metal, funeral doom, finnish doom metal, swedish doom metal |

| 7 | 20 | Floor Jansen | 96789 | 565353 | symphonic metal, gothic symphonic metal, fallen angel, gothic metal, hel |

| 10 | 18 | Atrium Carceri | 29838 | 130645 | dark ambient, dronescape, neofolk, power electronics, ambient industrial |

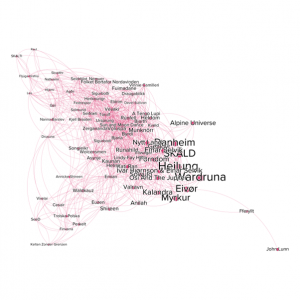

Community 2 is shown in more detail in Figure 3, using the layout algorithm by Hu (2012). These are then artists that are closely related to Wardruna, but unlike Figure 1’s network of artists directly related to Wardruna, this graph also takes second degree connections into account. Nevertheless, there is a considerable amount of overlap, with bands such as Heilung, SKÁLD, Eivø, Valravn, Nytt Land, and Sowulo featuring on both graphs. Figure 3 however includes more artists than Figure 1, and this network consists of 80 nodes and 890 edges. Notably absent from this graph is Faun, which as mentioned above belongs to Community 4. While Faun is therefore closely related to Wardruna, this band is also closely related to other (mainly German) bands, and hence Faun was grouped with the German community.

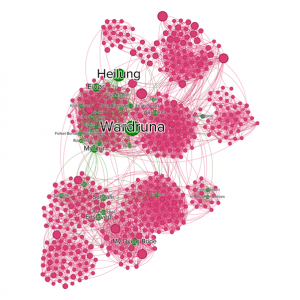

Figure 4 shows the same network as in Figure 2, but with artists that have performed at Midgardsblot in green. Labels are only provided for artists that have performed at Midgardsblot. It is striking in this graph that most of the artists that have performed at Midgardsblot can be seen in Community 2 alongside Wardruna, although other communities, such as the black metal community, Community 1, also contain numerous artists that have performed at this festival. Notably absent from Midgardsblot is however the German community, Community 4, even though the artists in this community are more popular on average than those in the other communities. This absence shows Midagardsblot’s emphasis on Scandinavian music: although not limited to Scandinavian bands, Midgardsblot often includes artists with ties to Scandinavia.

Discussion

The preceding discussion shows that Wardruna is linked to metal and black metal in particular, as noted in previous studies (Granholm 2011; Roe 2019; Fitzgerald 2023; Fitzgerald and Nordvig 2023). Figure 2 above shows Wardruna and Heilung – and similar artists – literally “adjacent to heavy metal subculture” (Fitzgerald and Nordvig 2023:192). Wardruna (and Heilung) indeed straddle the divide between traditional folk music and black metal, which Figure 2 shows clearly.

The network graphs also show that while Wardruna and Heilung are particularly important bands with a large number of followers, they are embedded into a large network of similar artists. Whether by using first degree connections or the modularity algorithm by Blondel et al. (2008), it was shown that artists such as Danheim, SKÁLD, Eivø, Valravn, Nytt Land, Sowulo and others are highly similar. While Wardruna and Heilung are particularly important, one should not lose sight of the fact that there are many other artists active in this field, and it would be prudent to also acknowledge the contributions of these artists to the Dark Nordic Folk scene.

Figure 2 also shows that while Wardruna is related to the black metal scene, the other music scene highlighted by Roe (2019) as a root of the Dark Nordic Folk scene, namely NeoFolk – as represented by bands such as Death in June, Current 93, and Sol Invictus – remains an important relation to the Dark Nordic Folk scene. Figure 2 therefore shows not only current relatedness, but also bears testament to the historical development of the Dark Nordic Folk scene.

Figure 4 shows the primacy of the Midgardsblot music festival in the Dark Nordic Folk scene, where a large number of the bands that are most similar to Wardruna have performed. In addition, Midgardsblot also connected different communities in this graph, thereby contributing to cohesion in this network.

An interesting finding is the exclusion of the German community from Midgardsblot. This may be due to a variety of reasons, but I suspect these bands have a weaker connection to black metal. Bands such as Unheilig and Faun also have a much less dark undertone than their Scandinavian counterparts.

The current study mentioned some collaborations in passing, but did not formally investigate the occurrence of collaborations. It would be interesting to see whether these collaborations strengthened cohesion in the communities presented in Figure 2, or provided linkages between communities. Future research could explore the nature and extent of collaborations in and around the Dark Nordic Folk scene.

In addition, it was noted earlier that the contributions of other Dark Nordic Folk artists should be acknowledged. Future research could focus on specific bands and how they relate to this music scene.

Conclusion

The current study has provided a comprehensive analysis of the Dark Nordic Folk music scene, focusing on the interconnectedness of different communities and the roles of key bands and the Midgardsblot festival. The network analysis revealed the intricate relationships between various subgenres within the scene, highlighting the significance of Wardruna and Heilung as central figures with extensive connections to other artists. The findings also underscored the historical development of the Dark Nordic Folk scene, demonstrating the ongoing relevance of NeoFolk and its connection to the contemporary music landscape. Additionally, the prominence of the Midgardsblot music festival in bringing together diverse artists and communities was evident, emphasising its role in fostering cohesion within the network.

Future research could delve into the nature and impact of collaborations within and across the Dark Nordic Folk scene. Exploring the dynamics of artistic partnerships and their contribution to community cohesion and cross-genre linkages would provide valuable insights into the evolving nature of the music scene. Furthermore, a more in-depth study of some of the other Dark Nordic Folk bands could shed light on how other bands contribute to this scene.

Bibliography

Anderson, A., Maystre, L., Anderson, I., Mehrotra, R. and Lalmas, M. 2020. Algorithmic effects on the diversity of consumption on spotify, in Huang, Y., King, I., Liu, T.-Y., and Steen, M. van (eds.) Proceedings of The Web Conference 2020. WWW ’20: The Web Conference 2020, New York, NY, USA: ACM:2155–2165. doi: 10.1145/3366423.3380281.

Anderson, I., Gil, S., Gibson, C., Wolf, S., Shapiro, W., Semerci, O. and Greenberg, D. M. 2020. ‘Just the way you are’: Linking music listening on Spotify and personality, Social psychological and personality science:1–12. doi: 10.1177/1948550620923228.

Arntzen, A. F. 2023. Odin rir metallen. En religionsvitenskapelig undersøkelse av bruk av symboler og elementerfra norrøn religion i norsk svartmetall. Master thesis. Universitet i Oslo.

Bastian, M., Heymann, S. and Jacomy, M. 2009. Gephi: An open source software for exploring and manipulating networks, Proceedings of the International AAAI Conference on Web and Social Media, 3(1):361–362.

Blondel, V. D., Guillaume, J.-L., Lambiotte, R. and Lefebvre, E. 2008. Fast unfolding of communities in large networks, Journal of Statistical Mechanics: Theory and Experiment, 2008(10):P10008. doi: 10.1088/1742-5468/2008/10/P10008.

Fitzgerald, P. and Nordvig, M. 2023. Spellbinding Skalds: Music as Ritual in Nordic Neopaganism, in Borkataky-Varma, S. and Ullrey, A. M. (eds.) Living Folk Religions. London: Routledge:191–203.

Fitzgerald, P. M. 2023. Til Valhall: The formation of Nordic Neopagan identity, religiosity, and community at a Norwegian heavy metal festival. Doctoral dissertation. University of Denver.

Fruchterman, T. M. J. and Reingold, E. M. 1991 Graph drawing by force-directed placement, Software: Practice and Experience, 21(11):1129–1164. doi: 10.1002/spe.4380211102.

Fumić, R., Rumac, M. and Orehovački, T. 2023. Evaluating the user experience of music streaming services, in Arai, K. (ed.) Intelligent computing: proceedings of the 2023 computing conference, volume 1. Cham: Springer Nature Switzerland (Lecture notes in networks and systems):668–683. doi: 10.1007/978-3-031-37717-4_43.

Granholm, K. 2011. ‘Sons of northern darkness’: Heathen influences in black metal and neofolk music, Numen, 58(4):514–544. doi: 10.1163/156852711X577069.

Gunstad, M. F. 2015. Rase og religion. Særtrekk ved Varg Vikernes’ ideologi sammenlignet med den klassiske nazismen. Master thesis. Universitet i Oslo.

Hu, Y. 2012. Algorithms for visualizing large networks, in Naumann, U. and Schenk, O. (eds.) Combinatorial Scientific Computing. London: Chapman and Hall/CRC:525–549. doi: 10.1201/b11644-20.

Kahn-Harris, K. 2007. Extreme metal: Music and culture on the edge. Oxford: Berg.

Martin, S., Brown, W. M., Klavans, R. and Boyack, K. W. 2011. OpenOrd: An open-source toolbox for large graph layout, in Visualization and Data Analysis 2011. IS&T/SPIE Electronic Imaging, SPIE (SPIE Proceedings):786806. doi: 10.1117/12.871402.

Peters, C. 2020. Lucky Leif und die bärtigen Männer, Mittelalter Digital, 2:118–163. doi: 10.17879/mittelalterdigi-2020-3290.

Rieder, B. 2023. Spotify Artist Network. https://labs.polsys.net.

Robb, J. 2013. Wardruna – An in depth interview with brilliant Norwegian band with Viking roots Music. https://louderthanwar.com/wardruna-an-interview-with-brilliant-norwegian-band-with-viking-roots-music-who-play-london-in-oct/ (Accessed: January 11, 2021).

Roe, S. 2019. Against the modern world: NeoFolk and the authentic ritual experience, Literature & Aesthetics, 29(2):15–31.

Senekal, B. A. 2021. Ou wyn in nuwe sakke: Die onlangse herlewing van die Germaanse kultuur op Instagram, LitNet Akademies Geesteswetenskappe, 18(2):132–160.

Skjoldli, J. and Gregorius, F. 2023. Feltnotat om Midgardsblot, DIN – Tidsskrift for religion og kultur, 1:107–110.

Sommer, T. 2020. Heilung: The must-see band of 2020 is The Flinstones in hell – Rock and Roll Globe. https://rockandrollglobe.com/experimental/heilung-the-must-see-band-of-2020-is-the-flinstones-in-hell/ (Accessed: January 4, 2021).

Trafford, S. 2021. Nata vimpi curmi da: Dead languages and primordial nationalisms in folk metal music, in Valijärvi, R.-L., Doesburg, C., and Digioia, A. (eds.) Multilingual metal music: Sociocultural, linguistic and literary perspectives on heavy metal lyrics. Bingley: Emerald Publishing Limited:223–240. doi: 10.1108/978-1-83909-948-920200020.

Unger, M. P. 2016. Sound, symbol, sociality: the aesthetic experience of extreme metal music. London: Palgrave Macmillan. doi: 10.1057/978-1-137-47835-1.

Von Schnurbein, S. 2016. Norse revival: Transformations of Germanic neopaganism. Leiden: Brill.