Title: Primary obstacles preventing students from the Faculty of Economics and Management Sciences (FEMS) from acquiring skills and competencies required by the Fourth Industrial Revolution

Anemarie Botha

Email: anemarie.botha@nwu.ac.za

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-6567-3757

Public Relations (Stellenbosch College), BA Com. Sc.(UNISA), Mphil (Stellenbosch University)

Lecturer at NWU (lecture planning, contact and teaching time with students, assessing student’s work, research)

Hester Vorster

email: Hester.Vorster@nwu.ac.za

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-8535-0672

HED (UP), BCom (UP), MPhil (NMU), Specialist Diploma: Mathematics (UJ)

Lecturer at NWU (Accounting)

Corresponding author: Prof. Anna-Marie Pelser

Email: ampelser@hotmail.com or anna.pelser@nwu.ac.za

iD ORCID: http://orcid.org/0000-0001-8401-3893

Research Professor, North-West University, Faculty of Economic and Financial Sciences- Entity Director –GIFT, Mahikeng Campus.

HED (Home Economics, PU for CHE), B Com (UNISA), B Com Hons (PU for CHE), M Com (Industrial Psychology, NWU), PhD (Education Management, NWU)

Ensovoort, volume 43 (2022), number 4: 1

Abstract

South African Universities are responsible for equipping students with employability skills and competencies required by the Fourth Industrial Revolution. Academics should empower students by developing their job-specific skills and soft skills such as communication, computer literacy, critical thinking, and creativity skills. The problem statement is that most of the programme outcomes in FEMS are aligned with the skills and competencies required by the Fourth Industrial Revolution, but certain obstacles prevent the transfer of these skills and competencies.

Therefore, the research question is: What are the obstacles preventing the transfer of skills and competencies required by the Fourth Industrial Revolution? This conceptual paper aims to review the obstacles that prevent students’ skills transfer required by the Fourth Industrial Revolution. Identifying these obstacles and interventions will contribute to students’ academic success and ensure that they are fully prepared and employable for their chosen careers.

First, the impact of the Fourth Industrial Revolution and the skills required will be discussed. The literature review and the researchers’ experiences and observations will focus on the primary obstacles that hinder students’ academic success and the transfer of employability skills. The preliminary critical barriers identified are the lack of self-efficacy; time management skills; academic literacy skills; and contextual barriers such as internet access, caregiving, family support, transport and textbooks.

Identifying the extent to which these barriers affect students may help in making informed decisions on appropriate remedial interventions. The paper recommends that a follow-up study be done amongst first-year students to determine what they perceived to be the vital obstacles preventing them from adapting and acquiring the skills and competencies required by the Fourth Industrial Revolution.

Keywords: Obstacles; Fourth Industrial Revolution skills; Employability skills, Competencies; Skills

Introduction

In South Africa, the challenge is to improve student’s skills to succeed in the Fourth Industrial Revolution. The Path to student success in the Fourth Industrial Revolution will be found in those Education institutions where lecturers can empower their students to see what needs to be done and accomplish it. According to Wilson, Brown and Hughes (2017:4), “machine creativity will eclipse biological creativity” in the Fourth Industrial Revolution. That will lead to a reduction in job opportunities. Change is therefore inevitable, and students have no choice but to acknowledge and cope with these changes to survive in the Fourth Industrial Revolution. Xing, Marwala and Marwala (2018:171) argue that students should “Adapt fast and quick” to succeed in the Fourth Industrial Revolution. According to Xing et al., (2018:174), new technology cannot replace the human touch and “are needed to finalise and coordinate implementation tasks”. Doucet, Evers, Guerra, Lopez, Soskil and Timmers (2018:130) state that universities should change degrees to help students prepare for the future. Students will then have to empower themselves to become problem solvers and creative thinkers (Ball, 2000:1008). The fourth Industrial Revolution will bring change and lead to more companies employing people with the skills needed by the Fourth Industrial Revolution.

Universities have to accept the influence of the Fourth Industrial Revolution and confront the factors that contribute to faculty hesitation in developing new study material. Therefore, this study reviews the obstacles that prevent students’ skills transfer that the Fourth Industrial Revolution requires.

Literature review

Okoli and Schabram (2010) defined three general forms of literature reviews: theoretical history (focusing on the research question), thesis literature review (allowing graduates to discuss papers that already exist on the subject under investigation) and stand-alone literature reviews (no primary data is collected and analysed). This stand-alone literature review is called a systematic literature review. By finding and reviewing scholarly articles and documents, it reviews existing literature papers related to the subject. This research is categorised as a systematic literature review study based on that.

An integrated systematic literature review was employed in this research. Multiple database searches reviewed literature that discussed the core elements of the concept. Databases that were used included Ebsco Host, Emerald, Eric, Elsevier, Google Scholar and journals. The researcher established the research goals in conducting a systematic literature review for this study, searched for related research that addressed the research goals, extracting information from the reviewed studies, checked for prejudice and vulnerabilities based on the information collected and rephrased the information to fit the goals of the study (Piper, 2013).

The literature review focuses on the required Fourth Industrial Revolution Skills, employability skills and obstacles facing students.

Required Fourth Industrial Revolution (4IR) Skills

The Fourth Industrial Revolution (4IR) would bring change and could also lead to more businesses employing people with the skills needed by the 4IR. Development in the workplace will become critical to secure future employment skills. Skills development is a subject that is often argued about. According to a report by The World Economic Forum (WEF:2018) in Davos, Switzerland, most of the present skills will not be applicable by the year 2022 by employees. There will be a sharp increase in technology design, analytical thinking and active learning. However,’ Human’ skills such as creativity, critical thinking, persuasion, and negotiation will rise in value. Emotional intelligence, leadership and social influence, as well as service orientation, will escalate in demand.

Xing and Marwala (2017:10-11) also stated that the world has reformed during the 4IR, and all graduates will face a world transformed by technology. They regarded the following skills as vital for the 4IR; critical thinking, people management, emotional intelligence, judgement, negotiation, cognitive flexibility, and knowledge production and management. Far (2019) expected technological skills to be the in-demand skill over the next decade. Other skills that will continue to be in demand are soft skills that will require social and emotional intelligence.

Mamabolo and Myers (2020:6) suggested critical skills as key to the 4IR. These critical skills are interdisciplinary. They identified the three main groups: Science, Technology, Engineering and Mathematics (STEAM), Social media, Mobile, Analytics and Cloud (SMAC) and Meta skills. According to them for STEAM, the skills are science -, technology -, engineering -, arts -, mathematics – and storytelling skills. For SMAC, they considered the following skills as essential; social media -, mobile device -, analytical – and cloud skills (digital literacy). The last group of skills they identified was the Meta skills that includes leading self-, social-intelligence-, complex-problem solving, and contextual intelligence skills.

Baird and Paramita (2019) noted similar skills that will be valuable to graduates, such as interpersonal skills; critical thinking/problem-solving skills; listening skills; oral/speech communication skills and professionalism. Collet, Hine and Du Plessis (2015:538) also noted that interpersonal, intrapersonal and the ability to collaborate with others are exceptional skills.

Employability Skills

The current changing business environment emphasises the importance of employability skills for graduates, focusing on developing skills to get a job and ensuring job security. Businesses are looking for a more adaptable and versatile workforce as they want to transform their organisations into being increasingly adaptable and versatile because of changing business sector needs. Yorke and Knight (2003:4) described employability as a collection of skills, understandings, and personal qualities that make graduates more likely to get a job and be productive in their chosen careers, benefiting themselves, the workplace, the community, and the economy.

Students additionally need to develop their competencies and gaining knowledge of skills. These skills and attitudes are fundamental to improving students’ employability as well as their learning. Employability is about having the skills needed to function properly at work (Martin, Villeneuve-Smith, Liz & McKenzie, 2008:8). Students should take responsibility for their development and make sure that they have the right employability skills (Peterson, 2001:181). Self-efficacy can also have an important role to play within graduate employability. Individuals with higher efficiency in their ability to fulfil instructional requirements for particular occupational roles appear to offer greater consideration and demonstrate higher pastime in a broader range of career opportunities. They also seem to train themselves for these positions more educationally and demonstrate greater patience when faced with demanding careers (Bandura et al., 2001). To succeed in the 4IR, students will have to change their negative attitude, believe in themselves and follow a “can do” approach to ensure future jobs. Students should overcome their fear of technology and develop leadership, socio-emotional intelligence, and critical thinking skills. According to Doucet et al., (2018:132), students must shift their mindset and embrace change by focusing on the present and lifelong learning.

Obstacles

Unfortunately, there are many obstacles hindering students’ academic success. South Africa underwent substantial political reform in 1994, from apartheid to democracy. Consequently, according to Steyn and Kamper (2011:116), former white-only universities, renowned for their high standards and academic success, attracted an increasing number of black students previously excluded from these universities. In higher education, there are traces of a history marked by social poverty and underachievement. According to Sebidi and Moreira (2017:35), social class plays a vital role in student success. Everyone has cultural and social assets, but these fluctuate in shape between societal groups, and some are more valued in unique settings than others. Particular cultural or social assets are enablers of academic success in higher schooling, and others are not (Sebidi & Morreira, 2017:36). A student from a middle-class family has a far greater chance of academic success compared to students less privileged. These obstacles that include a lack of financial resources needed to buy study material, cultural and social differences, language difficulties and being forced to adapt to circumstances in the city centres, hinder the achievement of tertiary-level black students, thus actively supporting past social exclusion and educational disparities. When there are no financial resources, the well-being of students is thus decreased because they cannot afford to buy laptops or data (Steyn & Kamper, 2011:116). Walker (2020:61) stated that money could allow full participation in higher education because, when freed from money troubles, a student will have a sense of peace, have enough to eat, access textbooks, and concentrate on his or her studies.

The challenges to overcome will be obstacles such as lack of self-efficacy, time-management skills, academic-literacy skills and context barriers that include internet access, caregiving, family support, transport and textbooks. These obstacles mentioned above are preventing students from acquiring the skills that are needed by the 4IR. In the next section, these primary obstacles will be discussed.

Self-efficacy

The article is grounded in Bandura’s (1997) theory of self-efficacy. The theory of self-efficacy refers to an individual’s belief in his or her ability to succeed in specific situations or carry out a task (Bandura, 1997). Therefore, one’s sense of self-efficacy will play a significant role in achieving goals and challenges. Individuals’ impression of their capacities likewise impact their points of view and passionate response during expectant and genuine exchanges with their condition (Bandura, 1981:201). Albert Bandura’s self-efficacy theory focuses on four sources of efficacy beliefs: mastery experiences, vicarious experiences, verbal persuasion, and emotional and physiological states.

The first source of self-efficacy is through mastering experience. To succeed, they must have successful experiences such as effective modelling in the classroom. Students should have opportunities to try the skill being learned while receiving feedback. According to Job and Sriraman (2015: 218), teaching should be student-centred, and students must have the opportunity to drive the conversation toward their own interests. Succeeding in mastering a task will build self-belief. Self-belief will positively change one’s attitude, giving one the freedom to make mistakes and cope with setbacks. Haidt and Rodin (1999:5) emphasised that self-belief can significantly impact performance in a given situation.

The second source of self-efficacy comes from the observation of role models. According to Lockwood (2006:37), a role model should contribute to one’s growth, share values and match the individual’s field of expertise. If one manages to find a role model who matches one’s field of expertise, it will allow more correspondence with oneself, compared to a role model in an “unrelated field and offers more information about one’s future prospects and potential” (Lockwood, 2006:37). Having individuals like ourselves succeed through their assisted effort strengthens our confidence that we do have the potential to ace the achievement exercises around there (Bandura, 2010:1). To change human behaviour, the third source, verbal influence, is generally utilised due to its straightforwardness and prepared accessibility (Bandura, 1981:204). Being persuaded that we can ace such exercises means that when problems occur, we are expected to spend and endorse the exertion (Bandura, 1981:204). The last source, emotional and physiological states, will add to how one judges one’s self-efficacy (Bandura, 1982:204). If an individual struggles with depression, it can undermine one’s certainty and might be deciphered as indications of powerlessness or lacklustre prowess (Bandura, 1982:204). Hutchison, Follman, Sumpte and Bodner (2006:39) stated that self-efficacy might impact the conduct of individuals, either emphatically or adversely, given their impression of their ability to perform a particular assignment. It impacts the decisions individuals make, the exertion they bring forth, and to what extent they continue notwithstanding impediments and disappointment.

Bandura (1977;982) estimated that apparent self-efficacy influences selection of “activities, effort and expenditure”. According to Schunk (1989:174), individuals who hold a low feeling of viability for achieving an undertaking may keep away from it. In contrast, those individuals who believe they are capable should participate more enthusiastically and continue longer than those who question their abilities. Students who lack self-efficacy are more likely to give up on goals and are not motivated. To succeed in the 4IR, lecturers should make sure students accomplish tasks. Lecturers will have to support students by giving them many opportunities for solving problems. Felder, Woods, Stice and Rugarcia (2000:4) recommended dividing the students into three or four groups and giving them enough time to brainstorm and generate ideas. Felder et al., (2000:4) emphasise that lecturers should not find fault with their ideas and list all ideas. When all students’ ideas are listed, lecturers are then allowed to add more ideas. The focus should be on improving their knowledge and skills. The more they practise, the better they will perform and improve their confidence and goals.

Time management skills

Time management skills will help students to achieve their goals. According to Bembenutty (2009:615), students with good time management skills concentrate on their priorities, engage in critical task preparation and develop plans to meet short- and long-term goals. “Time management can be viewed as an important performance outcome that students can use to self-regulate their current and future learning, and academic performance” (Zimmerman, Greenberg, & Weinstein, 1994:181). Students who are motivated will find it easier to self-regulate their learning and accomplish their tasks. Time management also allows one to achieve goals in a short period and succeed in the most effective ways (Akatay, 2003:282).

Academic literacy skills

Another obstacle contributing to a lack of self-efficacy is the low level of academic literacy students have. Academic literacy is the ability to engage in advanced reading, writing, listening and speaking skills (Butler, 2013:71). Weideman and van Dyk (2014:2) claimed that the capability of using language to satisfy the “demands of tertiary education” is called academic literacy. Sobuwa and McKenna (2019:13) claimed that “Academic language or ‘academic literacy’ is about more than the technical skills of reading and writing”. It included such practices as approaching a text with scepticism, seeing it as legitimate to take a personal position on a text. According to Sobuwa and McKenna (2019:13), students should be involved in the classroom and give their interpretation of the knowledge presented to them. Students then have to make sense of the knowledge while figuring out what is acceptable and what not.

In South Africa, most students study in their second language at the tertiary level, which significantly influences academic performance. A study was done by Roshandel, Ghonsooly and Ghanizadeh (2018:341) on “the role of students’ motivation and the effect it has on their self–efficacy.” The results revealed that motivation is connected to second language self-efficacy. Therefore, lecturers are responsible for recognising students motivating factors to enhance student learning (Hosseini, Ghonsooly & Ghanizadeh, 2017:172). Most students lack the skills to communicate effectively in a written format that will allow them to succeed after graduation (Defazio, Jones, Tennant & Hook, 2010:35). It is significant for students to understand the importance of academic literacy. General immersion in a learning language does not guarantee that students’ academic literacy will automatically grow to a degree appropriate t a postgraduate study setting (Kern, 2000:5). Students with high literacy skills are also more likely to be employed than students with poor academic literacy skills (Majid, Liming, Tong & Raihana, 2012:1036). The changing environment gives particular importance to employability, focusing on skills and practical experience (Weligamage, 2009:119). Welligamage (2009:124) emphasised the need to discover the talent set that will satisfactorily serve the future labour market. Therefore, the challenge for the future is likely to be, how to cope with increasing inequality and ensure adequate training, particularly for low-skilled workers (Arntz, Gregory & Zierahn, 2016:4). Students have to adapt to cope with change in the 4IR. Most tasks will be done mainly by machines instead of humans in the 4IR. Robots in the workplace are a threat to humans, but companies still need humans to do specific tasks. According to Arntz, Gregory and Zierahn (2016:10), tasks such as interpreting, persuading, negotiating or caring for others are, as a consequence, likely to remain human even in the long run.

Contextual barriers

Steyn and Kamper (2011:126) identified, amongst others, the following study and contextual barriers, namely: resources, caregiving, family support, transport and textbooks. University studies are costly because aside from the research material itself, it requires student events and housing involvement. The study conducted by Steyn and Kamper (2011:130) showed that most participants linked their shortage of finances to some aspect of poor academic performance: buying textbooks, being unable to supply the necessary needs for staying in residences and not being able to purchase laptops and data.

Resources

One of the skills for 4IR mentioned by all the authors is technology. It has also been identified as a contextual barrier in the South African context as students lack financial resources (Chux et al., 2016:174). Naude (2018:147) stated that critical technologies in the 4IR resulted from an overlapping of robotics with digital platforms, big data analytics and artificial intelligence (AI). According to Naude (2018:149), one of the obstacles will be that African countries cannot take in and use technologies. Livingstone and Bobber (2005:12) said that “Increasingly, children and young people are divided into those for whom the internet is an increasingly rich, diverse, engaging and stimulating resource of growing importance in their lives and those for whom it remains a narrow, unengaging, if occasionally useful, resource of rather less significance”. According to Livingstone and Bobber (2005:20), young people also had difficulties searching the web and evaluating website contents.

The gap between those who can use computers or mobile phones and those who cannot determine economic growth or poverty (Donner, 2008:146). Jenkins et al., (2009:28) stated:

“What you can do with ten minutes of access at a sitting on an outdated machine in a public library with mandatory filtering software and with no opportunities for storage or transmission pales by comparison with what you can do from a computer in your home which enjoys unfettered access, high bandwidth and continuous connectivity.”

Ngulube et al., (2009:66) studied the use of the internet and literacy amongst previously deprived students at a South African religious institute and found a shortage of computers. This hampered their access to the internet. Another obstacle was the cost of and need for Information and Communication Technologies (ICT). According to Uimonen (1997), it has been proposed that developing countries can use second-hand instruments. The problem with that is that these instruments tend to be slower and less powerful. This will lead to developing countries always lagging behind.

The youth of developing countries, such as South Africa, have limited access to the internet. Koss (2001:78) stated that the lack of technological availability would have long-term effects on young people in third world countries. They will not be able to participate in society effectively. According to Blignaut (2009:590-596), who studied digital inequalities in South Africa, millions of citizens still do not have exposure to Information Technology (IT), and although there are many national policies, non-governmental organisations and other development programmes to give citizens access to the internet, people’s lives did not show the impact thereof. According to him, the disparity in the nation’s access to the internet is influenced by the existence of a population’s socio-economic status, and in order to tackle technology access, the socio-economic level of the society needs to be elevated. Van Dijk (2005:20) stated that the unequal distribution of resources brings a sense of social exclusion and brings control in transferring information.

Letseka (2009:99) mentioned that as a product of apartheid, the downward spiral of financial disadvantage and inadequate academic performance still prevails in some of the South African Higher Education Institutions. Letseka revealed limited access to computers and the internet. These students have a disadvantage because of historical and economic circumstances. According to Walker (2020:60), students reported that their institutions required assignments in PDF format. According to him, YouTube is a precious tool for learning, and the internet provides a valuable source of data. Although some universities have computer labs, these have a time limit and is congested. Students that are staying off-campus cannot make use of these facilities after hours due to a lack of safe transport. Students feel that having access to money can help to buy them laptops and data.

Eastin and LaRose (2000) stated that online self-efficacy, or the trust in one’s ability to prepare and carry out online courses required to achieve such accomplishments, is a potentially important component in trying to break the digital divide between seasoned Internet users and beginners. Their understanding is that the digital divide was mainly viewed as regards race and class disparity patterns reflected in inequalities in access to technology and the internet. Self-efficacy is the belief “in one’s capabilities to organise and execute the courses of action required to produce given attainments” (Bandura, 1997:3). It is shown that people who have no confidence in using the web or who are uncomfortable using the web have poor self-efficacy attitudes. Self-efficacy is not a measure of ability; it is simply what people believe they could do with the abilities they possess. Odaci (2011:1109) noted that the internet, commonly used in educational settings, could be a valuable tool for teaching and learning when used in a way that fits its purposes. In a study done between university students, he found that as internet use became more troublesome, academic self-efficacy dropped. Eastin and LaRose (2000) believed that the digital divide was mainly considered in terms of race and class inequality trends that are embodied in inequality in software access and Web connectivity. While the value of class and race cannot be ignored, psychological and socio-economic and racial obstacles confront all novice Web users. Eastin and LaRose (2000) mentioned that the web’s most significant indicator of self-efficacy was previous internet usage and that it could take up to two years of practice to gain enough self-efficacy. This doubled the barrier for students without or little internet access.

Caregiving

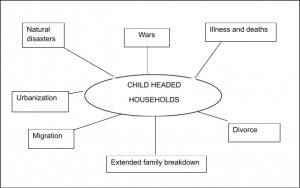

A second contextual barrier is caregiving. Participants in the study of Steyn and Kamper (2011:129) indicated constant anxiety about the safety of family members and that they worry about having enough money to meet the needs of family members. A reality in South Africa is that an increasing number of children are heading households and thus become caretakers. Reasons for this vary from being abandoned, the death of a parent(s) or labour migration. Mturi (2012:508) stated that houses run by children might have adult members, but the main factor is that children are accountable for the household’s daily operations and maintenance. According to Mogotiane (2010:29), the children (caregivers) running the households were responsible for providing food, clothes, housing, education and treatment for the sick people. Their duties include cleaning the house, washing clothes, cooking meals and helping siblings with homework. Such duties clashed with the child’s (care taker’s) education, and he/she is usually the first to leave school. Typically their only source of income is donations or child support grants.

The following challenges that child-headed households faced were identified by Maqoko and Dreyer (2007:724) as “a serious threat to education because of poverty, difficulties in obtaining food and shelter; high risk of being sexually abused by relatives and neighbours; the threat of child prostitution and child labour; difficulties in getting birth registration which is a prerequisite in procuring healthcare and social security benefits; and experiencing property grabbing by families and communities”. Makuyanaa et al., (2020:3-4) did a study under child-headed households (caregivers) and came to the following conclusions; participants indicated that they sometimes found it challenging to deal with issues, as they did not have a mentor to turn to for support. Issues they referred to were biological issues such as a change in their bodies, doing their homework and social problems. The researchers also noticed that most children were poorly dressed; they wore dirty clothes and had long hair that was not looked after.

Figure 1: The Framework of Causes of Child-headed Households adopted from Chigwenya et al., (2008:264)

Figure 1 (as shown above) is showing the factors that lead to Child Headed Households. Hanson and Molina (2019) cited the late Oliver Tambo: “Children of any nation are its future, a country, a movement, a person that does not value its youth and children does not deserve a future”. Makunyanaa et al., (2020:5-6) observed in their study that ‘Child Headed Households’ psychosocial deficits manifested as poor personal hygiene, lack of direction and evasion of difficult circumstances. The study also revealed that their families and communities manifested psychosocial shortfalls among children through abandonment, oppression and seclusion of children. These psychosocial problems led to self-efficacy problems as the children did not believe in their capabilities.

Family support

Family support was also identified as a contextual barrier in preventing students from acquiring the skills that are needed by the 4IR. Mturi (2012:509) noted that migration of parents caused child-headed households to be better-off as money was sent to them, and this gave them a better economic base. The traditional custom in Africa, where extended family members, such as aunts and uncles, supported such households, sadly, is no longer working the same as it used to. Extended relatives have historically handled orphans, but nowadays, this support system no longer functions, and numerous children are left to care for themselves. The family members would ensure that children were put in homes where an adult could support them. However, conventional support systems can no longer cope with the high incidence of adult deaths. Chigwenya et al., (2008:265) noted that family members and neighbours support these marginalised communities with safety nets by providing services. However, the expansion of society has now contributed to the collapse of such social platforms, introducing these young people to the vagaries of the challenging socio-economic and political climate. The extended family structure would no longer accommodate all those young adults who have lost family love and support.

Chigwenya et al., (2008:275) expressed that children without family support lacked the basic social and cultural values generally recognised in society. These children lacked self-efficacy and had low educational achievement levels, and had problems adapting to the real-life outside of their circumstances, such as that given to children in a ’‘natural” family set up. Mculu et al., (2016:99) studied young adults of child-headed households, and they found that most participants reported that they had experienced challenges with their academic work. They lacked self-efficacy in their academic work because they felt that their relatives or the community did not support them, and they have instead turned to crime or even prostitution as a way of survival.

Transport

According to Matsolo et al., (2018:76), transport played a significant role in students’ enrollment at higher educations. They also indicated that the distance travelled played a role in enrolment rates. Students who have enrolled indicated that the institutions were too far and had to drop out (Matsolo et al., 2018:78). Crea (2016:18) also indicated that transport was identified as a barrier. He also mentioned distance as an issue as most young people used walking as a mode of transport. Lucas (2010:16) pointed out that child-headed households were worried about transport costs and their challenges in obtaining an education. Lucas (2010:18) explained that travel costs consume their already modest earnings and add to these households’ concerns and financial strain, often making it almost impossible for them to access education. He explained that because of the cost of transport, most of their journeys involved long walks. These walks environments are generally unsafe because of no safe footpaths, and criminality worries are strong.

Lucas (2010:9) mentioned that the psychological impact of poverty was enormous. Many young adults have shown feelings of disappointment or frustration towards people that were better off than they were. He went on to say that at first, travel appeared unlikely to be strong on people’s priority list for worries, but in reality, it was different. This was mainly attributed to people needing to travel long distances to carry out their daily activities. This needed to be done, despite the fact that the transport cost was high relative to their low income.

Textbooks

The last contextual factor the lack of textbooks. Crea (2016:18) remarked that most students were concerned about issues related to content and education and the lack of study material. According to him, three to four students had to share textbooks, which led to students not studying independently. If students were to study together and concentrate on the work, one always gets that one student who is not concentrating. “From the existing literature, it appears that students have been deeply concerned with the cost of textbooks and report that these costs negatively impact their academic performance” (Martin et al., 2017:81). According to them, expensive textbooks can play a significant role because students select different parts of a course because they cannot afford these expensive textbooks. Kingkade (2011) mentioned that as the cost of textbooks continued to rise, many students chose to cut back on textbooks to save money. The high cost of textbooks led to many students feeling they are being abused within the system of higher education.

Conclusion

For the past several decades, lecturers have focused attention on the content of degrees and not on soft skills. However, heading towards the 4IR, soft skills are crucial for learning to get a future job. The focus has swift to life-long learning, and students will have to empower themselves to ensure they do not fall behind in the 4IR.. The future of students at all educational institutions must be prepared with soft skills. The importance of soft skills in students’ lives to find a future job were emphisized as the students with soft skills will distinguishes them from other candidates with a similar qualification. Unfortunately, many barriers were identified that hampered student’s success in empowering themselves with the necessary skills needed to survive in the 4IR. A follow-up study should be done amongst first-year students to determine what they perceived to be the vital obstacles preventing them from adapting and acquiring the skills and competencies required by the 4IR. Students will have to overcome several barriers in order to succeed in the 4IR. It is highly recommended that the students acquire these skills that lecturers incorporate more practical activities in their lessons to improve their students’ skills. If these skills are not developed, students will struggle to find a job in the 4IR.

References

Akatay, A. 2003. Time Management in Organization. Selcuk University Journal of Social Sciences Institute, 10, pp.281-289.

Arntz, M., Gregory, T. & Zierahn, U. 2016. The risk of automation for jobs in OECD countries.

Baird, A.M. & Parayitam, S. 2019. Employers’ ratings of importance of skills and competencies college graduates need to get hired: Evidence from the New England region of USA. Education and Training, 61(5): 622-634.

Ball, A.F. 2000. Empowering pedagogies that enhance the learning of multicultural students. Teachers College Record, 102(6), 1006-1034.

Bandura, A. 2010. Self‐efficacy. The Corsini encyclopedia of psychology, pp.1-3.

Bandura, A. 1997. Self-efficacy: The exercise of control. New York:W. H. Freeman.

Bandura, A. 1981. Self-referent thought: A developmental analysis of self-efficacy. Social cognitive development: Frontiers and possible futures, 200(1), p.239.

Baygi, A.H., Ghonsooly, B. & Ghanizadeh, A. 2017. Self-fulfillment in higher education: contributions from mastery goal, intrinsic motivation, and assertions. The Asia-Pacific Education Researcher, 26(3-4), 171-182.

Bembenutty, H. 2009. Academic delay of gratification, self-efficacy, and time management among academically unprepared college students. Psychological Reports, 104(2), 613-623.

Blignaut, P. 2009. A bilateral perspective on the digital divide in South Africa. Perspective on global development and technology, 8(4): 581–601.

Brynjolfsson, E., McAfee, A. & Spence, M. 2014. New world order: labor, capital, and ideas in the power law economy. Foreign Affairs, 93(4), 44-53.

Butler, G. 2013. Discipline-specific versus generic academic literacy intervention for university education: An issue of impact?. Journal for Language Teaching= Ijenali Yekufundzisa Lulwimi= Tydskrif vir Taalonderrig, 47(2), 71-87

Chigwenya, A., Chuma, M. & Nyanga, T. 2008. Trapped in the vicious circle: An analysis of the sustainability of the child-headed households’ livelihoods in ward 30, Gutu district. Journal of Sustainable Development in Africa, 10(3): 264-286.

Chux G.I., Ikechukwu., O.E. & Robertson, T. 2016. The Entrepreneurial Intention of University Students: The Case of a University of Technology in South Africa. Acta Universitatis Danubius: Oeconomica, 12(1): 164–181.

Collet, C., Hine, D. & Du Plessis, K. 2015. Employability skills: perspectives from a knowledge-intensive industry. Education and Training, 57(5): 532-559.

Crea, T.M. 2016. Refugee higher education: Contextual challenges and implications for program design, delivery, and accompaniment. International Journal of Educational Development, 46, pp. 12-22.

Defazio, J., Jones, J., Tennant, F. & Hook, S.A. 2010. Academic Literacy: The Importance and Impact of Writing across the Curriculum–A Case Study. Journal of the Scholarship of Teaching and Learning, 10(2), 34-47.

Donner, J. 2008. Research Approaches to Mobile Use in the Developing World: A Review of the Literature. The Information Society, 24(3): 140-159.

Doucet, A., Evers, J., Guerra, E., Lopez, N., Soskil, M. & Timmers, K. 2018. Teaching in the fourth industrial revolution: Standing at the precipice. Routledge.

Eastin, M.S. & LaRose, R. 2000. Internet Self-Efficacy and the Psychology of the Digital Divide. Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication 6(1).

Far, O.J.S. & Conversations, A. 2019. 4IR – What can we Expect and Plan for?

Felder, R.M., Woods, D.R., Stice, J.E. & Rugarcia, A. 2000. The future of engineering education II. Teaching methods that work. Chemical engineering education, 34(1), 26-39.

Haidt, J. & Rodin, J. 1999. Control and efficacy as interdisciplinary bridges. Review of general psychology, 3(4), 317-337.

Hanson, K. & Molima, C. 2019. Getting Tambo out of limbo: exploring alternative legal frameworks that are more sensitive to the agency of children and young people in armed conflict. In Research Handbook on Child Soldiers. Edward Elgar Publishing.

Hutchison, M.A., Follman, D.K., Sumpter, M. & Bodner, G.M. 2006. Factors influencing the self‐efficacy beliefs of first‐year engineering students. Journal of Engineering Education, 95(1), 39-47.

Jenkins, H. 2009. with Purushotma, R., Weigel, M., Clinton, K. & Robison, A.J. Confronting the Challenges of Participatory Culture: Media Education for the 21st Century.

Jenkins, J.J., Sánchez, L.A., Schraedley, M.A., Hannans, J., Navick, N. & Young, J. 2020. Textbook Broke: Textbook Affordability as a Social Justice Issue. Journal of Interactive Media in Education, 1(3), p.1.

Job, J. & Sriraman, B. 2015. The concept of teacher–student/student–teacher in higher education trends. Interchange, 46(3), 215-223.

Kern, R. 2000. Literacy and language teaching. Oxford University Press.

Kingkade, T. 2011. Rising costs force students to skimp on textbooks. Huffington Post. http://www.huffingtonpost.com/2011/08/11/studentadvocates-sound-alarm-on-textbooks_ n_924536.html

Knight, P. & Yorke, M. 2003. Assessment, learning and employability. McGraw-Hill Education (UK).

Koss, F.A. 2001. Children Falling into the Digital Divide. Journal of International Affairs, 55(1): 75–90.

Livingstone, S. & Bober, M. 2010. UK Children Go Online. London: Economic and Social Research Council. 2005. Çevrimiçi) http://personal. lse. ac. uk/bober/UKCGOfinalReport. pdf, 1(01).

Lockwood, P. 2006. “Someone like me can be successful”: Do college students need same-gender role models?. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 30(1), 36-46.

Lucas, K. 2010, January. The role of transport in the social exclusion of low income populations in South Africa: A scoping study. In Proceedings of Transportation Research Board Annual Meeting.

Majid, S., Liming, Z., Tong, S. & Raihana, S. 2012. Importance of soft skills for education and career success. International Journal for Cross-Disciplinary Subjects in Education, 2(2), 037-1042.

Makuyanaa, A., & Mbulayib, S.P. & Kangethec, S.M. 2020. Psychosocial deficits underpinning child headed households (CHHs) in Mabvuku and Tafara suburbs of Harare, Zimbabwe. Children and Youth Services Review 115:1-6

Mamabolo, A. & Myres, K. 2020. Bridging Africa’s Skills 4: 0 Gap: Repositioning Learning, Teaching, and Research of Skills in Higher Education Institutions. Teaching, and Research of Skills in Higher Education Institutions. SSHO-D-20-00076.

Maqoko, Z. & Dreyer, Y. 2007. Child-headed households because of the trauma surrounding HIV/ AIDS. Hervormde Teologiese Studies (HTS)/Theological Studies, 63(2), 717–31.

Martin, M., Belikov, O., Hilton, J., Wiley, D. & Fischer, L. 2017. Analysis of student and faculty perceptions of textbook costs in higher education. Open Praxis, 9(1):79-91.

Martin, R., Villeneuve-Smith, F., Liz, M. & McKenzie, E. 2008. Employability skills explored. London: Learning and Skills Network.

Matsolo, M. J., Ningpuanyeh, W. C. & Susuman, A. S. 2018. Factors Affecting the Enrolment Rate of Students in Higher Education Institutions in the Gauteng province, South Africa. Journal of Asian and African Studies, [s. l.], 53(1): 64–80.

Mculu, L.V., Mphephu, K.E., Madzhie, M. & Mudau, T.J. 2016. The challenges and coping strategies of child-headed households at Mkhuhlu, Mpumalanga province, South Africa. African Journal for Physical, Health Education, Recreation and Dance, December (Supplement 1:1), 95-104.

Mogotiane, S., Chauke, M., van Rensburg, G., Human, S. & Kganakga, C. 2010. A situational analysis of child-headed households in South Africa. Curationis, 33(3): 24–32.

Mturi, A. 2012. Child-headed households in South Africa: What we know and what we don’t. Development Southern Africa, 29(3): 506–516.

Naudé, W. 2018. Brilliant technologies and brave entrepreneurs. Journal of International Affairs, 72(1): 143-158.

Ngulube, P., Shezi, M. & Leach, A. 2009. Exploring network literacy among students of St Joseph Theological Institute in South Africa. South African Journal of Library and Information Science, 75 (1): 56–67.

Okoli, C. & Schabram, K. 2010. A guide to conducting a systematic literature review of information systems research.

Peterson, R.M. 2001. Course participation: An active learning approach employing student documentation. Journal of Marketing Education, 23(3), 187-194.

Piper, R.J. 2013. How to write a systematic literature review: a guide for medical students. National AMR, Fostering Medical Research, 1-8.

Roshandel, J., Ghonsooly, B. & Ghanizadeh, A. 2018. L2 Motivational Self-System and Self-Efficacy: A Quantitative Survey-Based Study. International Journal of Instruction, 11(1), 329-344.

Schulz, B. 2008. The importance of soft skills: Education beyond academic knowledge.

Schunk, D.H. 1989. Self-efficacy and achievement behaviors. Educational psychology review, 1(3), 173-208.

Sebidi, K. & Morreira, S. 2017. Accessing powerful knowledge: A comparative study of two first year sociology courses in a South African university. Critical Studies in Teaching and Learning, 5(2), 33-50.

Sobuwa, S. & McKenna, S. 2019. The obstinate notion that higher education is a meritocracy. Critical Studies in Teaching and Learning, 7(2), 1-15.

Steyn, M.G. & Kamper, G.D. 2011. Barriers to learning in South African higher education: some photovoice perspectives. Journal for New Generation Sciences, 9(1): 116-136.

Uimonen, P. 1997. Internet as a tool for social development. Annual Conference of the internet Society, INET.

Van Dijk, J.A. 2005. The deepening divide: Inequality in the information society. Sage Publications.

Walker, M. 2020. The well-being of South African university students from low-income households. Oxford Development Studies, 48(1): 56-69.

Weideman, A. & Van Dyk, T. 2014. Academic literacy: Test your competence. Forthcoming from ICELDA.

Weligamage, S.S. 2009. Graduates’ employability skills: Evidence from literature review. Sri Lanka: University of Kelaniya.

Wilson, C., Lennox, P., Brown, M. & Hughes, G. 2017. How to develop creative capacity for the fourth industrial revolution: Creativity and employability in higher education.

Wilson, C., Lennox, P., Brown, M. & Hughes, G. 2017. How to develop creative capacity for the fourth industrial revolution: Creativity and employability in higher education.

World Economic Forum. 2018. The Future of Jobs Report. Available at https://www.weforum.org/reports/the-future-of-jobsreport-2018

Xing, B. & Marwala, T. 2017. Implications of the fourth industrial age for higher education. The Thinker Issue 73, Third quarter 2017.

Xing, B., Marwala, L. & Marwala, T. 2018. Adopt fast, adapt quick: Adaptive approaches in the South African context. In Higher education in the era of the fourth industrial revolution (pp. 171-206). Palgrave Macmillan, Singapore.

Zimmerman, B.J., Greenberg, D. & Weinstein, C.E. 1994. Self-regulating academic study time: A strategy approach.