Dr. Burgert Senekal, University of the Free State

Ensovoort, volume 46 (2025), number 11: 3

Abstract

This study investigates the use of the hashtag, #nordicrunes, on Instagram. Using a network analysis that applies degree centrality, PageRank and modularity, it is shown which hashtags are used most often with #nordicrunes, as well as which are the most important hashtags and which hashtags are often used together. It is shown that hashtags relating to Norse Paganism, spirituality, tattoos, jewellery and other handmade items are particularly important. As such, the study shows that the runes are used for esoteric purposes, but also for more pragmatic purposes such as generating an income and creating art, and relating to the Norse Pagan community.

Keywords: folksonomy, Germanic, hashtags, heritage, Instagram, Norse Paganism, runes, Vikings

Introduction

There has been a resurgence of interest in various aspects of the Norse Pagan and Germanic past over the past few decades, including in history, art and religion (Von Schnurbein 2016; Rudgley 2018; Forssling 2020; Flowers 2021). According to Flowers (2021), some of this interest has been specifically focused on the runes, and various studies have already investigated the use of the runes and other related Norse Pagan phenomena on social media platforms such as Instagram (Bennett and Wilkins 2020; Downing 2020; Hanssen 2020; Senekal 2021). The popularity of the runes and Norse Pagan themes on Instagram can be seen in the sheer volume of posts: on 9 January 2024, there were 311,000 posts with #norsepagan, 399,000 posts with #asatru, 1.8 million posts with #odin, 12.1 million posts with #thor, 6.3 million posts with #vikings, 1.1 million posts with #runes, 902,000 posts with #heathen, and 6.4 million posts with #pagan. Compare these numbers with some other contemporary issues: on the same date, there were 372,000 posts with #slavaukraini (a hashtag that supports Ukraine in the war with Russia), 10,200 posts with #istandwithrussia (a hashtag that supports Russia’s war in Ukraine), 218,000 posts with #istandwithisrael, and 1000 posts with #istandwithpalastine. Some of these Norse-related hashtags like #vikings and #thor refer to television series and movies, while #heathen and #pagan are more general and may refer to other Pagan traditions, but even a more specialised hashtag such as #fornsiðr (meaning “old customs”) has generated 10,600 posts on Instagram (as on 9 January 2024).

The current study follows previous folksonomy network studies – studies that investigate the use of tagging by social media users – by analysing a hashtag network around the hashtag, #nordicrunes, on Instagram. Using a dataset spanning over a decade, it is shown which hashtags are most prominent and which ones occur together most frequently. The aim is to investigate how the runes are used on this social media platform.

The article is structured as follows. First, an overview of the runes is provided, including their origin and use throughout the last 2000 years. Thereafter, a short background on previous studies of folksonomy networks is provided. This is followed by a discussion of the methods used in the current study, followed by a presentation and discussion of the findings. The article concludes with summary remarks and suggestions for further research.

A short background to the runes

According to the Hávamál (verse 138-139) (Pettit 2023:112-113), Óðinn sacrificed himself to obtain the runes. Although this literary attestation dates to the thirteenth century, some runic inscriptions, such as the Sparlösa and Noleby stones, refer to the runes as a gift from the gods. The Noleby stone (Sweden, 6th century) reads, rūnō fāhi raginaku(n)dō[1] (“[I] paint the suitable rune derived from the gods”) (Antonsen 1975:55; Looijenga 2003:334; Düwel 2004:121, 2008:35; Birkett 2017:176). The Sparlösa stone (Sweden, around 800 CE) reads in the younger futhark, Ok rað runaR þaR ræginkundu þar, svað AlrikR lubu faði (“and guess (interpret) the runes that come from the guessers (gods) that Alrik lubu painted”) (Naumann 1998:707; Düwel 2008:36). This divine origin is supported by the meaning of the word rune, which is usually translated as “mystery, secret” (Knirk 2002:642; Looijenga 2003:8, 2020:826; Düwel 2004:121; Symons 2016:7). The term rūnō (plural rūnōR) is first attested in the inscription of the Einang stone from Norway (4th century) (Benoist 2018:51), although Mees (2006:221) believes that Tacitus’s mention of notae also refer to the runes.

The precise origin of the runes, and indeed of most scripts, remains unclear to this day (Salomon 2021). Some theories of the origin of the runes include that they were based on Etruscan (Mees 2000), Greek (Von Friesen 1933; Fairfax 2014) or Nabatean (Troeng 2003) scripts. The majority of runologists however argue that the runes were likely influenced by the Latin alphabet, although the latter was adapted for Germanic use (Moltke 1985:28; Nordisk Ministerråd 1997:34; Knirk 2002:637; Looijenga 2003:101; Düwel 2004:121; Fischer 2005:45; Düwel 2008:181; Looijenga 2020:820; Roost 2021:9; Magin and Smith 2023:123). Moltke (1985:40) argues, “the runic alphabet was not created ex nihilo: there are definite connections between the futhark and the ancient alphabets of the Mediterranean, the ancestor of which was North Semitic or Phoenician” (see also Düwel 2004:137). However, runes “were an independent creation based on Roman writing” (Moltke 1985:65).

If the runes were based on the Latin script, the question arises as to why adapt it and not simply employ the Latin script to write in the Germanic languages. One reason may be that the Latin alphabet was not particularly suited to writing the Germanic languages, which prompted an adaptation (Looijenga 2003:82). Looijenga (2003:82) believes that the adaptation might also have been related to the issue of identity, “The fact that they did not use the Roman script may be interpreted as a wish to deviate from the Romans, to express a cultural and political/military identity of their own.”

Regardless of their origins, runes date as far back as the 1st century CE, were the first writing system used by the Germanic peoples, and the system was used until it was superseded by the Latin alphabet (Moltke 1985:23). Moltke (1985:65) argues that Denmark is the most likely birthplace of the runes, a view shared by Looijenga (2020:822), although Magin and Smith (2023:123) place the origin in Denmark or Germany. The earliest find is the Vimose comb, dated to 160 CE in Denmark (Looijenga 2003:38; Düwel 2004:139), but it is usually assumed that there was a period before that where runes were in use but we have no evidence of their use (Knirk 2002:634; Düwel 2004:138). The Meldorf fibula, dated to the 1st century CE, has not been conclusively demonstrated to be a runic inscription (Looijenga 2003:38; Düwel 2004:139; Mees 2006:205).

The runic script is referred to as a futhark, based on the first six letters of this script (ᚠ, ᚢ, ᚦ, ᚨ, ᚱ, ᚲ), just as the Latin script is referred to as an alphabet after Septimus Florens Tertullianus (around 200 CE), based on the names of the first two letters in Greek (Griffiths 1999:164). Various futharks exist, but the main ones are the elder, younger, Anglo-Frisian and mediaeval futhark (Moltke 1985:28; Nordisk Ministerråd 1997:34; Looijenga 2020:821; Magin and Smith 2023:121). The elder futhark dates to around 50-700 CE, was found across the Germanic settlements and consists of 24 runes (Moltke 1985:28; Nordisk Ministerråd 1997:34; Düwel 2004:125; Looijenga 2020:820; Roost 2021:8). The younger futhark dates to 700-1100 CE, is found in Scandinavia, England, the Isle of Man and Ireland, and consists of 16 runes (Moltke 1985:28; Nordisk Ministerråd 1997:34). Anglo-Frisian runes date to 400-800 CE and were found in Frisia and England (Moltke 1985:27; Nordisk Ministerråd 1997:34). During the Viking age, the younger futhark also existed in a long- and short stave version, along with a staveless version (Moltke 1985:28; Nordisk Ministerråd 1997:34; Knirk 2002:640; Magin and Smith 2023:123). The Mediaeval futhark dates to 1100-1500 CE and is found in Scandinavia, the Faroes, Iceland and Greenland (Moltke 1985:30-31; Nordisk Ministerråd 1997:34).

Runes were written left to right, right to left, or in boustrophedon, where they were written alternating left to right and right to left (Moltke 1985:28; Knirk 2002:636; Benoist 2018:10; Magin and Smith 2023:124). The latter use is however uncommon (Düwel 2004:122). In addition, runes could be combined to form bind runes, or they could be used in ideographic form by writing the rune for its corresponding concept, e.g. ᚠ (fehu) for “cattle” or “wealth” (Moltke 1985:34; Knirk 2002:636; Düwel 2004:123). Despite attempts at interpreting the names of the runes, it seems likely that these names simply served a mnemonic function (Knirk 2002:636).

Runes have an esoteric connotation and overtly magical inscriptions occur in runes from about 400 CE (Benoist 2018:48; Flowers 2021:44). The plethora of magical inscriptions in the elder futhark makes it clear that the runes are inextricably bound up with magical practices (Benoist 2018:47-50). After the adoption of Christianity, runes continued to be used, often by Christian clerics and often in a magical context. Flowers (2021:36) argues,

It is interesting to note that although the runes were replaced by the Latin alphabet as a consequence of a new religion being introduced, the new letters themselves do not seem to have been interpreted as having any special or awesome powers. Yet – as the use of runes to write Latin prayers or Mediterranean magical formulas indicates – the runes retained their status as a sacred script even into the Christian period (original emphasis).

Glassman (2017:1282) believes that runes were used primarily in a magical context; indeed, “when writing was first brought to the north from Rome, the tribespeople simply believed that the ‘Runes’ brought magical spells with them” (Glassman, 2017:1369). This perception that the runes were only used for magical purposes is however circumspect, since there are documented cases of runes being used only for communication purposes (Looijenga 2020:827). One example is the Gallehus horn (dating to around 400 CE and found in Denmark), which reads, ek HléwagastiR hóltijaR hórna táwido “I, Leugast (Greek Kleoxenos) son/descendant of Holt (or: wood/forest dweller) made the horn”) (Düwel 2004:127). Düwel (2004:127) argues that it has been impossible to decipher this inscription on the elaborately decorated horn as anything other than a maker’s formula inscription. According to Düwel (2004:121) the runes, like any other script, is a tool for communication that can be utilised for both magical and profane purposes. Moltke (1985:60) also disputes theories that the runes were primarily magical symbols,

All alphabets […] have one thing in common: they are first and foremost a means of communication. Whatever supernatural powers may be credited with the invention of the alphabet in any given culture, the alphabet is not per se magical. The letters of any alphabet can be used for messages magical and un-magical, but there is no magic inherent in the letters. Many scholars (even alphabet historians) have lost sight of this when dealing with runes, in spite of the fact that nothing in the nature, names, occurrence or shapes of runes distinguishes them from any other letters used among mankind (original emphasis).

Rune use declined by the late middle ages, but according to Magin and Smith (2023:121) and Düwel (2004:124), they were used up until the 19th century. Beginning with Johan Bure and Ole Worm around 1600 CE, runes were studied extensively over the next few centuries, as discussed in detail by Flowers (2021).

At the end of the 20th century, the ISO Runes Project (Nordisk Ministerråd 1997) offered suggestions for standardising the runes in order to create digital renditions of them. Instrumental figures in this creation were Helmer Gustavsson from Sweden, James Knirk from Norway, Klaus Düwel from Germany, Ray Page from Great Britain, and Marie Stoklund from Denmark (Magin and Smith 2023:122). Runic symbols were introduced in Unicode 3.0 (1999) and expanded in Unicode 7.0 (2014), and currently include the elder and younger futharks, the Anglo-Saxon runes, and the mediaeval futhark. Microsoft Windows 7 and later supports runic symbols, and so does Google Docs. Various online transliteration tools currently exist, as well as smartphone applications that allow the user to transliterate Latin to runic script. In addition, numerous runic fonts and keyboards exist that can be installed on various operating systems, as listed by Webb (2017). This digital version of the runes allowed for their use on social media platforms. The forms of many runes vary greatly, just like all handwriting, hence the Unicode renderings of the runes should be viewed as idealised renditions (Nordisk Ministerråd 1997:18). As highlighted in Magin and Smith (2023), these idealised versions of the runes are far from perfect, but rune use as studied in the current article have found the idealised versions useful.

The Unicode renderings of the runes from the elder and younger futharks can be seen in Table 1. Names of runes are from Looijenga (2003:7). Note in particular that while the elder futhark ᛉ and younger ᛘ are near-identical, Unicode distinguishes between the two, as proposed by Nordisk Ministerråd (1997:30).

Table 1. The Unicode renderings of the runes

| Rune | Letter | Name | Name English | Elder/Younger |

| ᚠ | f | fehu | cattle | elder |

| ᚢ | u | uruz | ox | elder |

| ᚦ | þ | þurisaz | giant, thorn | elder |

| ᚨ | a | ansuz | a god | elder |

| ᚱ | r | raidō | wagon, wheel | elder |

| ᚲ | k | kaunan | tumour, torch | elder |

| ᚷ | g | gebō | gift | elder |

| ᚹ | w | wunjō | lust, pleasure | elder |

| ᚺ | h | hagalaz | hail, bad happenings | elder |

| ᚾ | n | naudiz | need, fate, destiny | elder |

| ᛁ | i | īsaz | ice | elder |

| ᛃ | j | jāran | year, harvest | elder |

| ᛇ | ei | īwaz | yew tree | elder |

| ᛈ | p | perþō | ? | elder |

| ᛉ | z | algiz | elk, rush | elder |

| ᛊ | s | sōwilō | sun | elder |

| ᛏ | t | tīwaz | Tyr, the sky god | elder |

| ᛒ | b | berkanan | birch | elder |

| ᛖ | e | ehwaz | horse | elder |

| ᛗ | m | mannaz | man | elder |

| ᛚ | l | laguz | lake, water | elder |

| ᛜ | ŋ | ingwaz | Ing, fertility god | elder |

| ᛞ | d | dagaz | day | elder |

| ᛟ | o | ōþalan | heritage, posession | elder |

| ᚠ | f/v | fé | cattle, money | younger |

| ᚢ | u/o/v | úr | aurochs, rain | younger |

| ᚦ | þ, ð | þurs | giant | younger |

| ᚬ | a | áss | the god | younger |

| ᚱ | r | raið | a ride, thunderclap | younger |

| ᚴ | k, g, ng | kaun | a sore | younger |

| ᚼ | h | hagall | hail | younger |

| ᚾ | n | nauð | need, bondage, fetters | younger |

| ᛁ | i, e | íss | ice | younger |

| ᛅ | a | ár | year, harvest | younger |

| ᛋ | s | sól | sun | younger |

| ᛏ | t, d, nt, nd | tyr | the god Tyr | younger |

| ᛒ | b, p, mb | bjarkan | birch(-goddess) | younger |

| ᛘ | m | maðr | man, human | younger |

| ᛚ | l | lögr | sea, waterfall | younger |

| ᛦ | ʀ | yr | yew | younger |

Runes are still in use today and are utilised by runologists, artists, reenactors, heathens, and history lovers. The far right has also been using runes since before World War II, and in 2019, there was a false rumour that the Swedish government was considering outlawing the usage of runes (Juridikfronten 2019). The Bluetooth logo, which bears Harald Bluetooth’s name, is another well-known example from the modern era, which is a combination of ᚼ (H) + ᛒ (B). Flowers (2021:238-241) also argues that the peace sign (☮) is in fact the ᛦ (yr) rune, which, during World War II, was employed to denote death in Soviet propaganda and initially by the anti-Nazi left.

As the remainder of this article discusses, in addition to these modern uses, runes have also become popular on Instagram, a social networking platform.

Previous research on folksonomy networks

A variety of network studies of folksonomy networks have been conducted using a diverse set of social media platforms, often focusing on the structure of folksonomy networks. Previous studies analysed folksonomy networks on platforms such as del.icio.us (Shen and Wu 2005; Cattuto et al. 2007; Lux, Granitzer and Kern 2007; Munk and Mørk 2007), Twitter (Laniado and Mika 2010; Türker and Sulak 2017), Instagram (Ichau, Frissen and d’Haenens 2019; Buente et al. 2020; Senekal 2020), and Tumblr (Bourlai 2018; Brett and Maslen 2021; Price and Robinson 2021). In general, these studies have found that folksonomy networks exhibit familiar structural features of complex networks such as power law distributions (Shen and Wu 2005; Lux, Granitzer and Kern 2007; Munk and Mørk 2007; Türker and Sulak 2017) and small-worldedness (Shen and Wu 2005; Senekal 2020). The current study focuses on hashtag use rather than folksonomy network structure, and therefore studies by Bennett and Wilkins (2020), Downing (2020), Hanssen (2020), and Senekal (2021) are of particular relevance, since these studies investigated hashtag use regarding Norse or Germanic content on Instagram. While these studies did not employ a network approach, I provide a short overview of their findings because of their relevance to the current study.

Bennett and Wilkins (2020) analysed the cultural processes by which individuals in the 21st century adapt and inscribe Viking runes as tattoos on their bodies and share images of these tattoos on Instagram, exploring the role of Viking identity in shaping contemporary identities in the age of social media. Downing (2020) used interviews with Instagram account owners who identified as Heathen and used specific hashtags to understand the dynamics of religious communication on Instagram, finding that these young females applied theological thought in their posts and had a sense of responsibility to teach others about Heathenry. Hanssen (2020) used interviews, fieldwork, and web ethnography to examine how Neo-Pagan men in Oslo portray masculinity, comparing three different Neo-Pagan trends and analysing their expressions of masculinity through Instagram photos. The study concludes that while Neo-Paganism is often seen as allowing for diverse gender expression, some groups have a more homogenised expression of masculinity while others have a more heterogeneous expression. Senekal (2021) analysed posts with the hashtag #germanic on Instagram from 2012 to 2020, categorising the most common hashtags and determining the extent of interest in the Germanic world, finding a clear connection to Scandinavian culture, a focus on the Dark Ages, and an increase in interest over time.

The following section discusses the methods used in the current study.

Methods

Data gathering

The current study focuses on users’ posts made on Instagram with the hashtag, #nordicrunes. This hashtag was chosen because the hashtag, #runes, delivered an overwhelming number of posts on Instagram (1.1 million), which would have been unfeasible to download and analyse using the methods described below. The hashtag, #nordicrunes, delivered a more manageable dataset that could be analysed in its entirety, which was necessary in order to evaluate hashtag use over time, as well as study hashtag co-occurrences and conduct topic modelling.

Data was scraped from Instagram on 9 January 2024 using the Apple app, Instabro (https://instabro.app/). This app allowed the scraping of Instagram usernames (anonymised), the post itself, the date of the post, the number of likes and comments, and the type of post (picture, slide or video). Only public posts were included. All posts made with the hashtag #nordicrunes over the past decade were collected, from 2014-01-01, but since the current study is conducted at the beginning of the year, posts made after 2023-12-31 were removed from the dataset in order to include data for full years.

Data processing

After scraping the data, the dataset was imported into Google Sheets for further analysis. Since hashtags are contained within the caption itself, hashtags were extracted from post captions. Using the extracted hashtags, nodes and edges tables were created for the network analysis described below. The nodes table consists of posts and hashtags, while the edges table consists of posts and hashtags used in that post.

Emojis were also extracted from the captions of posts, because it was believed that emoji use could shed further light on the nature of runic use on Instagram.

It was also investigated whether users use the runes in their captions, rather than simply posting about the runes using the Latin script. Runes were therefore extracted from post captions and their occurrences counted, with the aim of determining how often runes are used in captions and which runes occur the most often.

As in Senekal (2021), the language of posts was considered to shed light on which language communities are interested in runic material on Instagram. The language of posts was determined by querying Google’s Natural Language API from within Google Sheets.

Table 1 provides an overview of the dataset. It can be seen here that more than 9,000 Instagram posts were included in the analysis, which were posted over a period of ten years. A total number of 165,000 hashtags were used, of which over 26,000 are unique hashtags. The average hashtags per post of 17.8 compares favourably with previous studies of hashtag use (albeit slightly higher), where Dorsch (2018) found an average of 15 hashtags per post, and Senekal (2021) found an average of 17 hashtags per post. Only 154 posts (1.66% of posts) contain actual runes in the caption, whereas all other posts relate to the runes using the Latin script.

Table 1. An overview of the dataset.

| Variable | Value |

| Posts | 9276 |

| Users | 3995 |

| Period (years) | 10 |

| Average posts per day | 2.54 |

| Average posts per user | 2.32 |

| Average words per post | 6.89 |

| Average likes per post | 106.89 |

| Average comments per post | 3.05 |

| Number of hashtags used | 165393 |

| Average hashtags per post | 17.83 |

| Number of posts without hashtags | 484 |

| Number of unique hashtags | 26276 |

| Number of languages | 56 |

| Number of captions containing runes | 154 |

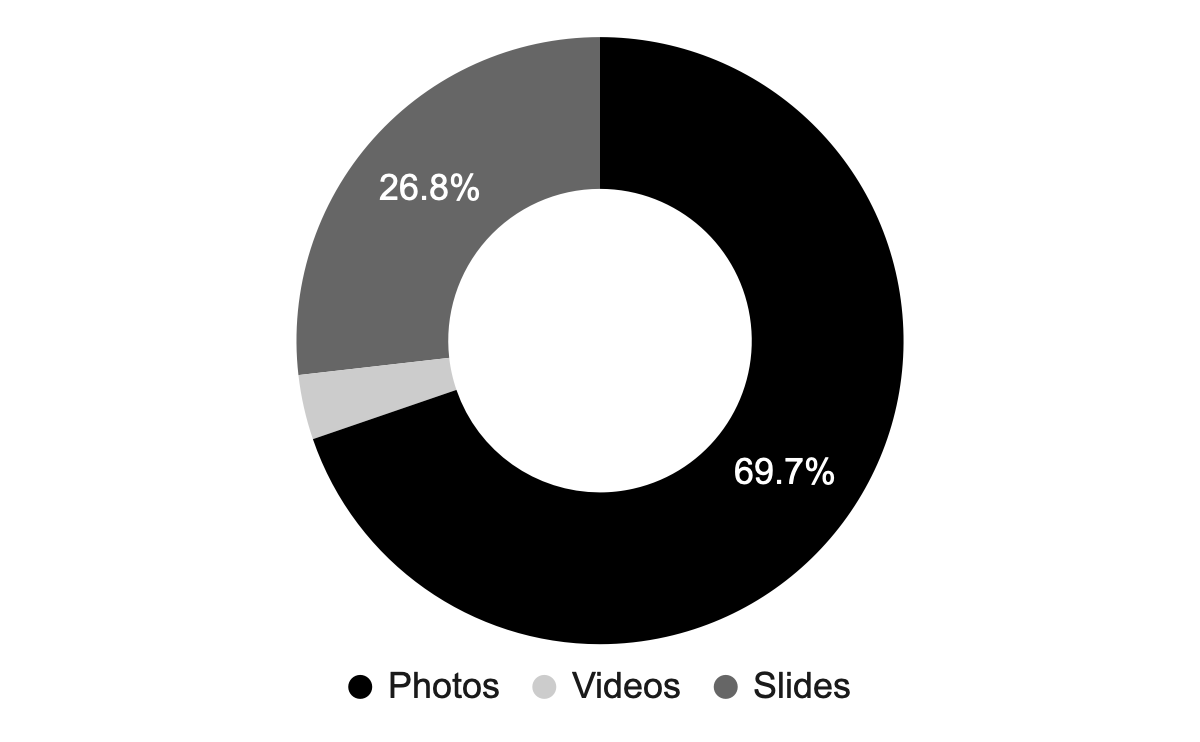

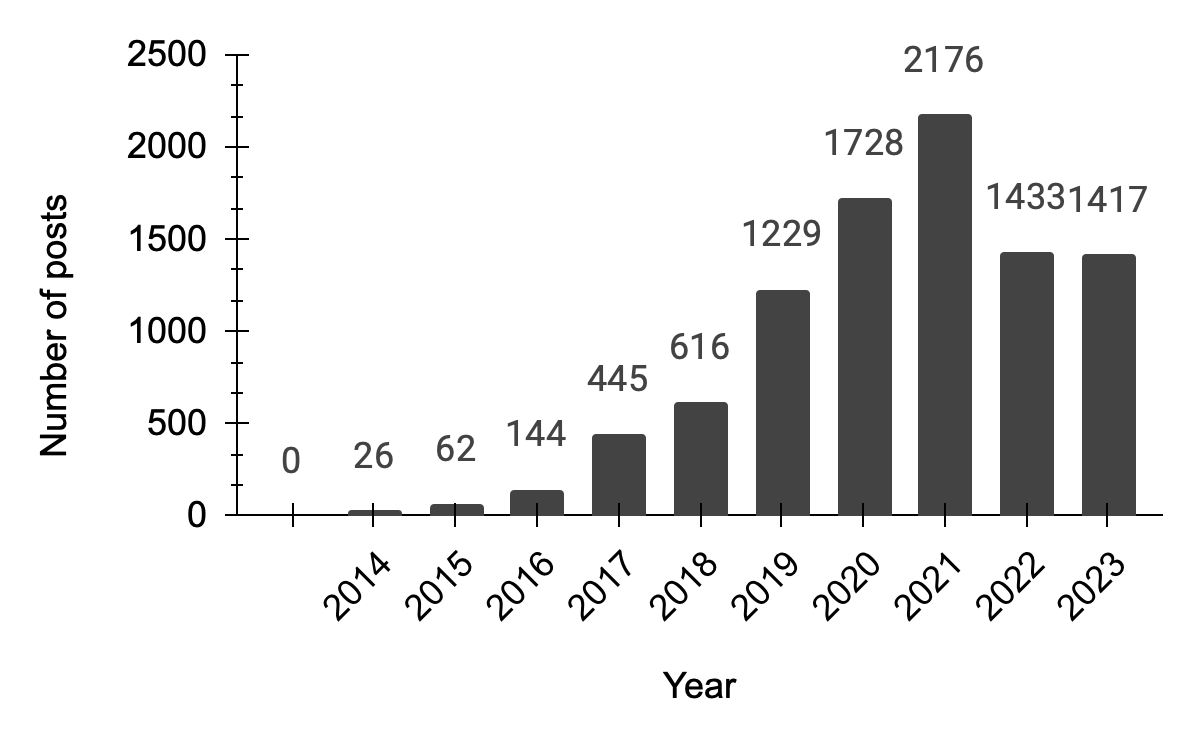

Figure 1 provides a more detailed overview of the use of #nordicrunes on Instagram. Figure 1A shows that the majority of posts are in photo format, followed by photo slides, with just 3.4% of posts in video format. This is to be expected on Instagram, which is primarily a photo sharing platform. Nevertheless, slides are more popular with #nordicrunes than with #germanic, where 96% of posts were in photo format, 0.6% in slide format and 3.6% in video format (Senekal 2021:146). This shows that people posting about the runes have a greater need to include more than one picture per post than what is the case with #germanic.

Figure 1B shows that there has been a steady increase in the number of posts with the hashtag, #nordicrunes, and that if posts prior to 2014 had been included in the analysis below, it would not have influenced the analysis to a great extent. The decline after 2021 is difficult to explain without a close examination of the posts themselves, but may be related to the end of the television series, Vikings, in 2021.

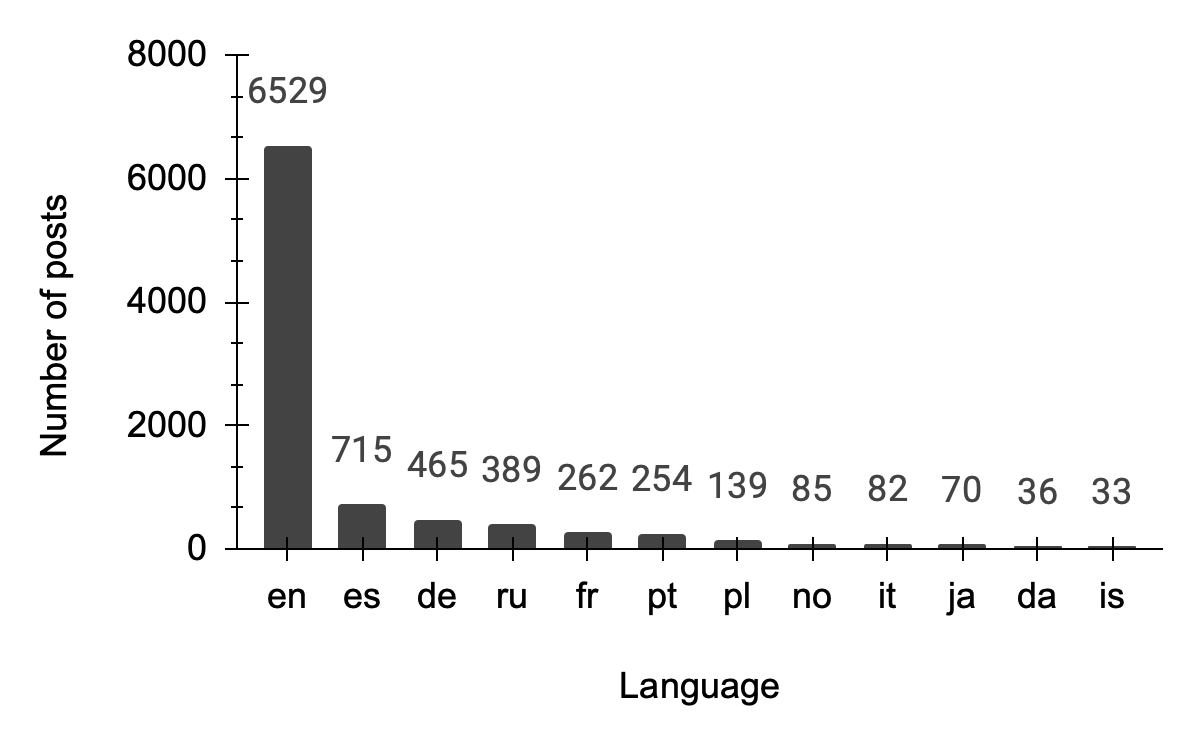

Figure 1C shows the ten languages that are used most often in these posts. Senekal (2021:146) found that posts made with the hashtag, #germanic, were mostly made in English (49%), followed by German (4%) and Portuguese (2%). Posts made with #nordicrunes are also dominated by English, with 72% of posts in English, followed by Spanish (8%) and German (5%). English posts are therefore in the overwhelming majority, thus confirming English’s dominance in this discourse as well. Other languages in the top ten include Russian, French, Portuguese, Polish, and Norwegian, but English’s dominance means that very few posts are made in these languages. It is however noteworthy that the most popular languages include Italic (Spanish, Portuguese, French, and Italian) and Slavic languages (Russian and Polish), which shows that interest in the runes is not confined to Germanic language communities (English, German, Norwegian, Danish and Icelandic in Figure 1C). The occurrence of Japanese is further surprising, and on closer examination it came to light that these posts use different scripts to post information about spirituality.

| 1A. Types of posts | 1B. Posts over time |

|

|

| 1C. The top languages of posts | |

|

Figure 1. An overview of the dataset.

Data analysis

Hashtag occurrences can be analysed from the perspective of network science when an edge (also known as a link or a tie) is indicated between posts and hashtags that were used in the post. In this configuration, there are two types of nodes in the network: posts and hashtags, and the network is therefore known as a bipartite network (Newman, 2018:115). This network can be projected to a single-mode network by indicating edges between hashtags that co-occur, or between posts that share hashtags. This projection was not necessary for the current study, since the aim was to identify important hashtags and groups of hashtags, and this can be done using the bipartite rendition of the network.

I first wanted to identify the most important hashtags in the hashtag network. Network science has numerous centrality measures available that can highlight the most important nodes in a network, such as degree-, betweenness-, closeness-, Eigenvector-, Katz- and PageRank centrality (Newman 2018). The simplest centrality measure is degree centrality, which is typically a metric of activity that counts the connections a node has to other nodes in the network. Equation 1 is used to calculate degree centrality (CD), where (ni) is a node in a set of nodes and d(ni) is the node’s degree (Bibi et al. 2018). In the bipartite network analysed below, degree centrality will be equal to the number of posts in which a hashtag occurs.

C_D (n_i)=d(n_i) (1)

One of the more advanced centrality measures is PageRank centrality (Brin and Page 1998). The founders of Google created the PageRank centrality algorithm to determine a page’s ranking in search results, based on the notion that a page is significant if a large number of other significant pages link to it. PageRank is computed using the likelihood that a user will visit a page if they click on a random link from another page. While originally developed for ranking web pages, this centrality measure has demonstrated its utility in a variety of fields (Newman 2018:166). PageRank is calculated using Equation (2), where d is the damping factor, PR(nj) is used to represent the PageRank of node nj and OD(nj) represents the out-degree of node nj (Bibi et al. 2018).

PR(n_i)=Σ_(j=1)^n (PR(n_j))/(OD(n_j))+(1-d)/N (2)

There is an amount of overlap between degree and PageRank values, and in the current study, a near perfect correlation of r = 0.99 was calculated between degree and PageRank scores. For this reason, only degree centrality scores are used below (simply called “number of posts” in Figure 2), and PageRank values are indicated with larger labels in the network graph in Figure 3 below and in highlighting important nodes in the largest communities.

Apart from determining which hashtags play an important role in the discourse around #nordicrunes, I also wanted to determine which hashtags often occur together, as this will suggest themes or topics by which posts can be grouped. One of the most successful ways to cluster nodes together in network science is by using the Louvain method or modularity (Q), which counts the number of edges that connect two sets of nodes to determine which communities they belong to. Using this strategy, the number of edges discovered is compared to the number of edges that one would expect if edge formation happened at random. Modularity (Q) is calculated using Equation 3 (Blondel et al. 2008:2). In Equation 3, Aij represents the weight of the link between nodes i and j, ki = ∑j Aij is the sum of the weights of the links connected to node i, ci is the community to which node i is assigned, the δ function δ (u, v) is 1 if u = v and 0 otherwise, and (Blondel et al. 2008:3).

Q=1/2m ∑_(i,j) [A_ij-(k_i k_j)/2m]δ(c_i c_j ) (3)

Blondel et al.’s (2008) modularity algorithm assigns an arbitrary number to communities in order to label them, and these numbers are used in the discussion below.

As in the study of hashtag networks by Ichau, Frissen and d’Haenens (2019), Gephi (Bastian, Heymann and Jacomy 2009) was used to conduct a network analysis. Ichau, Frissen and d’Haenens (2019) also used Blondel et al.’s (2008) modularity to group hashtags together.

The following section discusses the results of the current study.

Results and discussion

Popular hashtags, runes and emojis

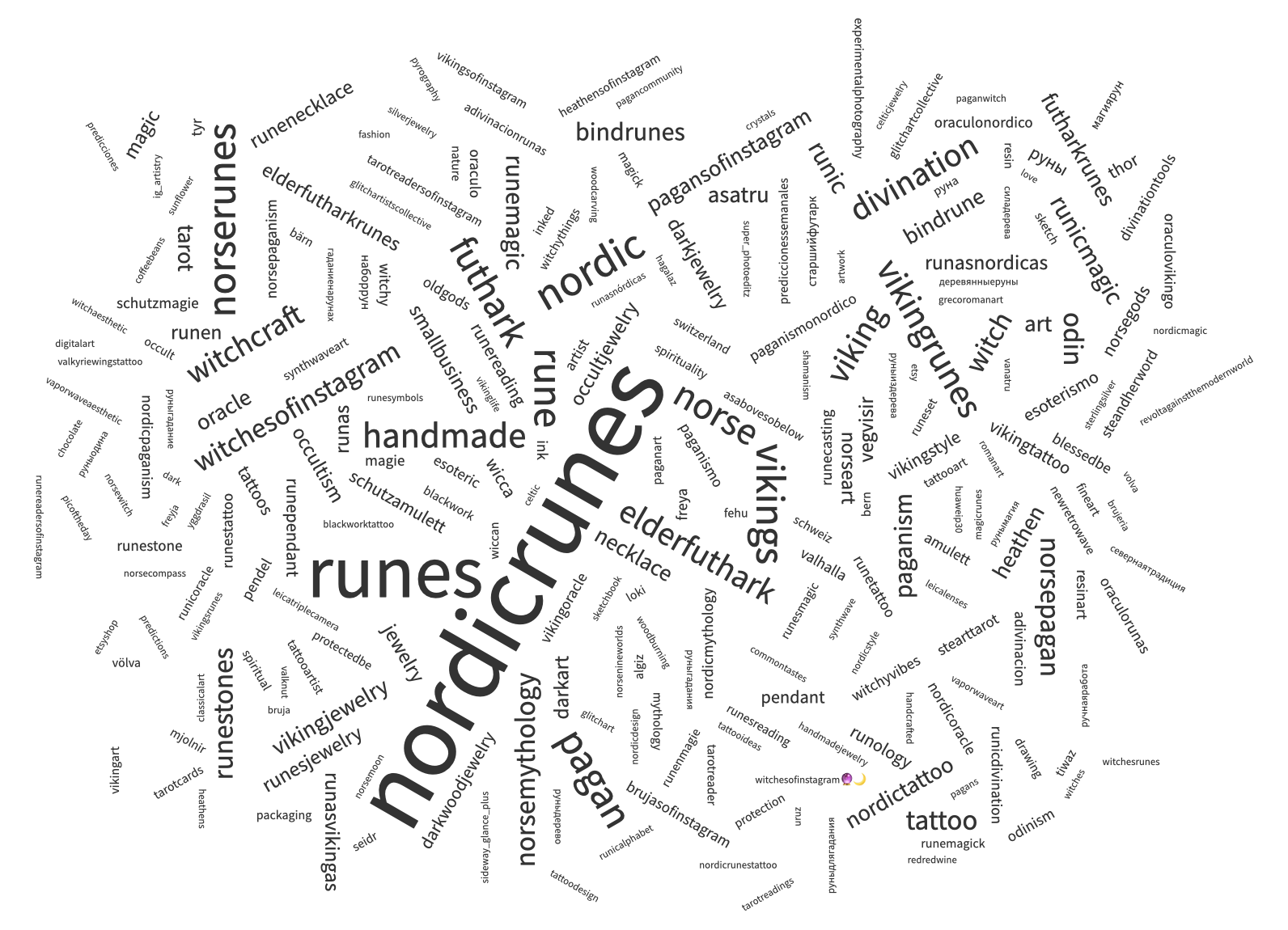

Figure 2 shows the most popular hashtags, as determined by the number of captions they occur in. It can be seen here that hashtags related to mystical practices occur often, such as #tarot, #witchcraft, #witchesofinstagram, #divination, and #runemagic. Numerous hashtags also tie in with the Norse Pagan community, such as #norsemythology, #odin, #pagan, #pagansofinstagram, #norsepagan, #heathen, #valhalla, and #norsegods. There are also hashtags related to handmade goods and commerce, such as #handmade, #jewelry, #vikingjewelry, #runesjewelry, #pendant, #smallbusiness, and #necklace. Some hashtags relate specifically to tattoos, such as #tattoo, #nordictattoo, #runestattoo, and #vikingtattoo. The hashtags that occur most often therefore show a strong connection with spirituality and Norse Paganism, as well as with tattoos and handmade items, especially jewellery.

Table 2 shows the runes and emojis that occur most frequently in these Instagram posts. The rune found most often is ᚠ (fehu), which is the first rune in the futhark and is associated with wealth, while ᚢ (uruz) is the second rune in the futhark and associated with oxen. It is difficult to make conclusions about the popularity of these runes without studying posts in detail, since runes may be associated with different concepts by different users, but it is striking that of the first six runes in the futhark, five occur on the list of the ten most popular runes. It may therefore be that many posts simply spell out futhark (ᚠᚢᚦᚨᚱᚲ). It should however be kept in mind that rune use is rare, and even around a hashtag focused on the runes (#nordicrunes), actual runes are not used often. Regarding emoji use, the five most popular emojis all seem to suggest esoteric use, and note that plant emojis also occur often. Pagan religions are known as nature-based religions, and hence the most popular emojis support what was found above with the most popular hashtags: posts made with the hashtag, #nordicrunes, are often made in the context of spirituality and paganism.

Table 2. The runes and emojis that occur most frequently.

| Rune | Count | Emoji | Count |

| ᚠ | 106 | 🧿 | 297 |

| ᚢ | 104 | 🪬 | 121 |

| ᚱ | 100 | ✨ | 111 |

| ᚨ | 74 | 🔮 | 92 |

| ᚾ | 74 | 🔥 | 72 |

| ᛚ | 68 | 🌿 | 62 |

| ᛁ | 58 | 🌱 | 49 |

| ᛏ | 58 | 💜 | 49 |

| ᛟ | 51 | 🍃 | 48 |

| ᚲ | 45 | 🖤 | 43 |

| ᛒ | 38 | 💕 | 39 |

| ᛉ | 31 | ❤ | 30 |

| ᛖ | 31 | 🦚 | 29 |

| ᚦ | 30 | 🌙 | 26 |

| ᚷ | 27 | 🎃 | 25 |

| ᛋ | 25 | 🌃 | 24 |

| ᛗ | 22 | 📷 | 20 |

| ᚹ | 18 | 🤍 | 20 |

| ᛞ | 18 | ⚡ | 19 |

| ᛃ | 16 | ◾ | 17 |

Themes

The algorithm by Blondel et al. (2008) identified 135 communities, which shows a diverse online discourse that uses hashtags in a large number of combinations. This is to be expected, since for globally active users hashtags have unique personal connotations. The majority of communities consist of very few nodes, while a small number of communities contain larger numbers of nodes. The largest community (Community 105) consists of 15.67% of nodes, followed by Community 40 (9.78% of nodes), Community 114 (8.1% of nodes), Community 1 (6.06% of nodes) and Community 30 (5.83% of nodes). In this section, I discuss the ten largest communities.

The nodes in Community 105 with the highest PageRank values are #tattoo, #art, #nordictattoo, #tattoos, #vikingtattoo, #runetattoo, #ink, #runestattoo, #artist, and #inked. The largest hashtag community therefore relates to the use of runes for tattoos, indicating that this is one of the most popular uses of runes on Instagram.

The nodes in Community 40 with the highest PageRank values are #divination, #witchcraft, #witch, #witchesofinstagram, #pagansofinstagram, #magic, #tarot, #wicca, #witchy, and #resinart. This second largest community therefore relates to hashtags associated with occult and esoteric practices, as was earlier suggested through emoji use and the most popular hashtags.

The nodes in Community 114 with the highest PageRank values are #nordic, #viking, #norsemythology, #odin, #paganism, #vikingstyle, #valhalla, #odinism, #nature and #protection. This third largest community is therefore tied to Norse Paganism and the Vikings, indicating that the runes are used often in this context. Note also the primacy of Óðinn, which is to be expected given his importance in Norse Paganism and specifically in relation to the runes. The occurrence of #nature is tied to the nature-based character of Paganism in general, as was seen earlier with emoji use.

The nodes in Community 1 include #drawing, #sketch, #sketchbook, #digitalart, #illustration, #blackandwhite, #graphic, #animals, #smoke, #alcoholmarkers. This community is therefore related to visual art, showing that the runes are often employed in artworks.

The nodes in Community 30 include #nordicrunes, #nordicmythology, #spirituality, #völva, #history, #nordicmagic, #oldways, #allfather, #odinsrunes and #runelore. The fact that this is the community to which #nordicrunes belong make this a particularly important community, because these are the concepts most closely associated with this hashtag. The hashtag is therefore closely associated with spirituality, history, and Óðinn (Allfather), but the use of #allfather rather than #odin suggests a more knowledgeable use of Norse Pagan material.

The nodes in Community 91 include #etsy, #etsyshop, #halloween, #etsyseller, #etsysellersofinstagram, #vikingcompass, #sun, #clay, #purple, and #handmadewithlove. This is clearly a community focused on using the runes in a practical sense by manufacturing and selling handmade items on Etsy. In this case, the runes obtain a monetary value by becoming a design element in handmade items.

The nodes in Community 104 include #runes, #fehu, #runasnórdicas, #pagans, #vanatru, #amulet, #coven, #ritual, #oráculo, and #ルーンカードリーディング. Like Community 40, this community revolves around spirituality, but hashtags are often in Spanish, which suggests that runes function here in a different linguistic community. The hashtag, #ルーンカードリーディング, means “rune card reading” in Japanese.

The nodes in Community 81 include #rune, #vikings, #norse, #norserunes, #futhark, #elderfuthark, #handmade, #norsepagan, #runemagic, and #runic. Like Community 91, this community focuses on using the runes for handmade items, but uses other platforms to sell items than Etsy. Other hashtags in this community refer to jewellery in particular, such as those hashtags shown in Figure 2 above.

The nodes in Community 78 include #photography, #cosplay, #nordicwitch, #bookstagram, #originalcharacter, #medieval, #larp, #book, #model, and #ragnarlothbrok. This community uses the runes as part of their alternate identities in cosplay, and note the main character from the television series, Vikings, as well as the suggestion that people dress up and post photographs of themselves.

The nodes in Community 110 include #runestones, #futharkrunes, #runereading, #runesreading, #magicrunes, #runicalphabet, #runereader, #runereadersofinstagram, #guidance and #runestaves. Like Communities 40 and 104, this community uses the runes for divination, although different hashtags are used.

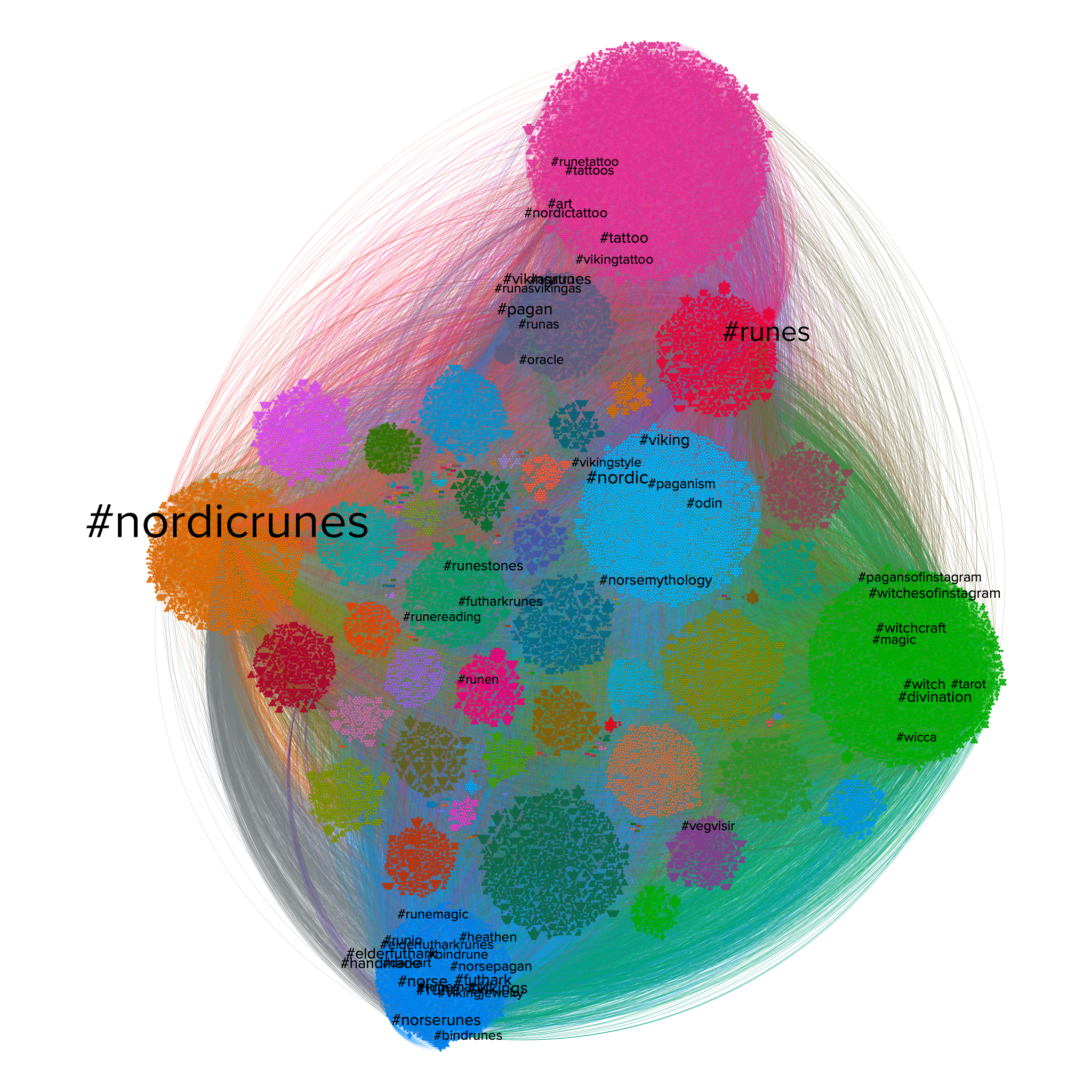

Figure 3 shows the hashtag network in the form of a network graph. For the sake of legibility, only the labels of the 50 hashtags with the highest PageRank values are indicated. Community 105 is indicated with pink at the top of the graph in Figure 3, Community 40 is indicated with green on the right, Community 114 with light blue centre right, Community 1 in dark green bottom right, and Community 30 in orange on the left. This graph provides a more nuanced overview of hashtag use on Instagram around #nordicrunes: while the largest community highlighted above relates to the use of runes for tattoos, the most important hashtags overall often belong to Community 81 (in dark blue at the bottom of Figure 3). While a smaller community, the use of runes in jewellery is therefore of particular importance on Instagram.

An interesting outlier is the hashtag, #vegvisir (purple cluster bottom right), which has the 35th highest PageRank value of all hashtags. This symbol dates to a later Mediaeval Icelandic manuscript and was not originally part of Viking Age imagery, but Taylor (2022:145-147) argues that the vegvisir is in one way not a Viking symbol, yet in another sense it has become a Viking symbol. In Senekal (2021:151), the vegvisir was highlighted as the second most important symbol associated with the hashtag, #germanic, and its importance in Figure 3 illustrates to what extent this symbol has become part of the Nordic/Germanic milieu.

Discussion

The findings of this study reveal several patterns and trends in the use of the #nordicrunes hashtag on Instagram. The most popular hashtags are related to mystical practices, Norse Paganism, tattoos, and handmade goods. This suggests that the use of runes on Instagram is closely tied to spirituality, esotericism, and personal expression through body art and handmade items.

The analysis of hashtag co-occurrences identified several communities within the hashtag network. The largest community is centred around the use of runes for tattoos, indicating that this is a popular and significant aspect of runic expression on Instagram. Other communities are focused on spirituality, Norse Paganism, visual art, handmade items, and cosplay. These findings highlight the diverse range of interests and activities associated with the use of runes on the platform.

One notable finding is the dominance of English in the posts made with the #nordicrunes hashtag. English-language posts account for the majority of content, followed by Spanish and German. This suggests that the use of runes on Instagram extends beyond Germanic language communities and has a global reach. It would be interesting to further explore the motivations and interests of non-Germanic language users in their engagement with runic material.

Another interesting finding is the association of runes with handmade items, particularly jewellery. This indicates that the runes have become a design element in the creation of unique and personalised accessories. It would be valuable to investigate the motivations and inspirations behind the incorporation of runes into handmade goods and explore the significance of these items within the broader context of contemporary runic practices.

One limitation of this study is the reliance on publicly available data from Instagram. While this provides valuable insights into the use of the #nordicrunes hashtag, it may not capture the full range of runic practices and interests. Future research could consider incorporating qualitative methods such as interviews or surveys to gain a deeper understanding of individuals’ motivations, beliefs, and experiences related to the use of runes on social media.

Additionally, the analysis focused on the hashtag network and did not explore the content of individual posts in detail. A closer examination of the actual posts could provide further insights into the specific themes, narratives, and visual representations associated with the use of runes on Instagram. This could involve a qualitative content analysis to identify recurring motifs, narratives, and symbols in runic posts.

Furthermore, the study primarily focused on the contemporary use of runes on Instagram. Future research could consider a comparative analysis of the use of runes across different social media platforms and online communities. This could shed light on how the use of runes varies across different online spaces and how these variations are influenced by the platform’s features, user demographics, and community norms.

Conclusion

This study provides insights into the contemporary use of runes on Instagram, highlighting the diverse range of interests and activities associated with the #nordicrunes hashtag. The findings suggest that the use of runes on Instagram is closely tied to spirituality, personal expression, and the creation of unique handmade goods. Further research is needed to explore the motivations, experiences, and meanings behind the use of runes in these contexts, as well as to investigate the use of runes across different social media platforms and online communities.

Bibliography

Antonsen, E. H. 1975. A concise grammar of the older runic inscriptions. Tübingen: Max Niemeyer Verlag GmbH & Co KG.

Bastian, M., Heymann, S. and Jacomy, M. 2009. Gephi: An open source software for exploring and manipulating networks, Proceedings of the International AAAI Conference on Web and Social Media, 3(1):361–362.

Bennett, L. and Wilkins, K. 2020. Viking tattoos of Instagram: Runes and contemporary identities, Convergence: The International Journal of Research into New Media Technologies, 26(5–6):1301–1314. doi: 10.1177/1354856519872413.

Benoist, A. D. 2018. Runes and the origins of writing. London: Arktos Media.

Bibi, F., Khan, H., Iqbal, T., Farooq, M., Mehmood, I. and Nam, Y. 2018. Ranking authors in an academic network using social network measures, Applied Sciences, 8(10):1824. doi: 10.3390/app8101824.

Birkett, T. 2017. Reading the Runes in Old English and Old Norse Poetry. London: Routledge.

Blondel, V. D., Guillaume, J.-L., Lambiotte, R. and Lefebvre, E. 2008. Fast unfolding of communities in large networks, Journal of Statistical Mechanics: Theory and Experiment, 2008(10):P10008. doi: 10.1088/1742-5468/2008/10/P10008.

Bourlai, E. E. 2018. ‘Comments in Tags, Please!’: Tagging practices on Tumblr, Discourse, Context & Media, 22:46–56. doi: 10.1016/j.dcm.2017.08.003.

Brett, I. and Maslen, S. 2021. Stage whispering: Tumblr hashtags beyond categorization, Social Media + Society, 7(3):205630512110321. doi: 10.1177/20563051211032138.

Brin, S. and Page, L. 1998. The anatomy of a large-scale hypertextual Web search engine, Computer Networks and ISDN Systems, 30(1–7):107–117. doi: 10.1016/S0169-7552(98)00110-X.

Buente, W., Rathnayake, C., Neo, R., Dalisay, F. and Kramer, H. K. 2020. Tradition gone mobile: an exploration of #betelnut on instagram, Substance Use & Misuse, 55(9):1483–1492. doi: 10.1080/10826084.2020.1744657.

Cattuto, C., Schmitz, C., Baldassarri, A., Servedio, V. D. P., Loreto, V., Hotho, A., Grahl, M. and Stumme, G. 2007. Network properties of folksonomies, AI Commun., 20:245–262.

Dorsch, I. 2018. Content description on a mobile image sharing service: Hashtags on instagram, Journal of Information Science Theory and Practice, 6:46–61.

Downing, R. 2020. Hashtag heathens: Contemporary Germanic Pagan feminine visuals on Instagram, Pomegranate: The International Journal of Pagan Studies, 21(2):186–209. doi: 10.1558/pome.40063.

Düwel, K. 2004. Runic, in Murdoch, B. and Read, M. (eds.) Early Germanic Literature and Culture. Rochester: Camden House:121–148.

Düwel, K. 2008. Runenkunde. Stuttgart: Springer-Verlag.

Fairfax, E. 2014. The twisting path of runes from the Greek alphabet, NOWELE, 67(2):173–230. doi: 10.1075/nowele.67.2.03fai.

Fischer, S. 2005. Roman Imperialism and Runic Literacy: The Westernization of Northern Europe (150-800 AD). Doctoral dissertation. Uppsala University.

Flowers, S. E. 2021. Revival of the Runes: The Modern Rediscovery and Reinvention of the Germanic Runes. Rochester, Vermont: Inner Traditions.

Forssling, G. E. 2020. Nordicism and Modernity. Cham: Springer International Publishing. doi: 10.1007/978-3-030-61210-8.

Glassman, R. M. 2017. The Origins of Democracy in Tribes, City-States and Nation-States. Cham: Springer International Publishing. doi: 10.1007/978-3-319-51695-0.

Griffiths, A. 1999. The fubark (and ogam): order as a key to origin, Indogermanische Forschungen, 104:164–210.

Hanssen, J. A. 2020. #paganmen. Iscenesettelse av maskulinitet hos nypaganistiske grupper. Master thesis. Universitetet i Oslo.

Ichau, E., Frissen, T. and d’Haenens, L. 2019. From #selfie to #edgy. Hashtag networks and images associated with the hashtag #jews on Instagram, Telematics and Informatics, 44:101275. doi: 10.1016/j.tele.2019.101275.

Juridikfronten 2019. Contrary to reports – No proposal for ban on runes in Sweden. https://www.juridikfronten.org/2019/06/04/contrary-to-reports-no-proposal-for-ban-on-runes-in-sweden/ (Accessed: November 12, 2021).

Knirk, J. E. 2002. Runes: Origin, development of the futhark, functions, applications, and methodological considerations, in Bandle, O., Braunmüller, K., Jahr, E. H., Karker, A., Naumann, H.-P., and Teleman, U. (eds.) The Nordic Languages. An International Handbook of the History of the North Germanic Languages. Berlin: Walter de Gruyter:634–648.

Laniado, D. and Mika, P. 2010. Making sense of twitter, in Patel-Schneider, P. F., Pan, Y., Hitzler, P., Mika, P., Zhang, L., Pan, J. Z., Horrocks, I., and Glimm, B. (eds.) The semantic web – ISWC 2010. Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer Berlin Heidelberg (Lecture notes in computer science):470–485. doi: 10.1007/978-3-642-17746-0_30.

Looijenga, T. 2003. Texts & contexts of the oldest runic inscriptions. Leiden: Brill Academic Publishers.

Looijenga, T. 2020. Germanic: Runes, Prace Historyczne, (20):819–853. doi: 10.36707/palaeohispanica.v0i20.371.

Lux, M., Granitzer, M. and Kern, R. 2007. Aspects of broad folksonomies, in 18th International Conference on Database and Expert Systems Applications (DEXA 2007). 18th International Conference on Database and Expert Systems Applications (DEXA 2007), IEEE:283–287. doi: 10.1109/DEXA.2007.80.

Magin, E. M. and Smith, M. 2023. (r)unicode: encoding and sustainability issues in runology, Digital Humanities in the Nordic and Baltic Countries Publications, 5(1):121–136. doi: 10.5617/dhnbpub.10657.

Mees, B. 2000. The North Etruscan thesis of the origin of the Runes, Arkiv för nordisk filologi, 115:33–82.

Mees, B. 2006. Runes in the first century, in Runes and their Secrets: Studies in Runology. Copenhagen: Museum Tusculanum Press:201–231.

Moltke, E. 1985. Runes and their origin: Denmark and elsewhere. Copenhagen: National Museum of Denmark.

Munk, T. B. and Mørk, K. 2007. Folksonomies, tagging communities, and tagging strategies–an empirical study, Knowledge Organization, 34(3):115–127. doi: 10.5771/0943-7444-2007-3-115.

Naumann, H.-P. 1998. Runeninschriften als Quelle der Versgeschichte, in Düwel, K. (ed.) Runeninschriften als Quellen interdisziplinärer Forschung. Berlin: Walter de Gruyter:694–714.

Newman, M. 2018. Networks. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Nordisk Ministerråd 1997. Digitala runor. En historisk skrift i datorns värld. København: Nordiska ministerrådet.

Pettit, E. 2023. The Poetic Edda: A dual-language edition. Cambridge, UK: Open Book Publishers. doi: 10.11647/OBP.0308.

Price, L. and Robinson, L. 2021. Tag analysis as a tool for investigating information behaviour: comparing fan-tagging on Tumblr, Archive of Our Own and Etsy, Jurnal Distilasi, 77(2):320–358. doi: 10.1108/JD-05-2020-0089.

Roost, J. 2021. Elliptical Epigraphy–What text types and formulas can tell us about the purpose of Gallo-Latin and Elder Futhark inscriptions. Doctoral dissertation. Universität Basel.

Rudgley, R. 2018. The return of Odin: The modern Renaissance of Pagan imagination. Rochester, Vermont: Inner Traditions.

Salomon, C. 2021. Comparative perspectives on the study of script transfer, and the origin of the runic script, in Haralambous, Y. (ed.) Grapholinguistics in the 21st Century, Part I. Grapholinguistics in the 21st Century, Brest, France: Fluxus Editions:143–199. doi: 10.36824/2020-graf-salo.

Senekal, B. A. 2020. Instagram volksonomie as komplekse netwerke, Suid-Afrikaanse Tydskrif vir Natuurwetenskap en Tegnologie, 39(1):61–67. doi: 10.36303/SATNT.2020.39.1.792.

Senekal, B. A. 2021. Ou wyn in nuwe sakke: Die onlangse herlewing van die Germaanse kultuur op Instagram, LitNet Akademies Geesteswetenskappe, 18(2):132–160.

Shen, K. and Wu, L. 2005. Folksonomy as a Complex Network, ArXiv, abs/cs/0509072.

Symons, V. 2016. Runes and Roman letters in Anglo-Saxon manuscripts. Berlin: De Gruyter.

Taylor, A. A. 2022. Tattoos, ‘tattoos,’ vikings, ‘vikings,’ and vikings, in Martell, J. and Larsen, E. (eds.) Tattooed bodies: theorizing body inscription across disciplines and cultures. Cham: Springer International Publishing:145–162. doi: 10.1007/978-3-030-86566-5_7.

Troeng, J. 2003. A Semitic origin of some runes, Fornvännen, 98(4):290–305.

Türker, İ. and Sulak, E. E. 2017. A multilayer network analysis of hashtags in Twitter via co-occurrence and semantic links, International Journal of Modern Physics B:1850029. doi: 10.1142/S0217979218500297.

Von Friesen, O. 1933. Runorna. Stockholm: A. Bonnier.

Von Schnurbein, S. 2016. Norse revival: Transformations of Germanic neopaganism. Leiden: Brill.

Webb, T. J. 2017. Write runes on your computer. https://webbmaster.com/2017/11/write-runes-on-your-computer (Accessed: November 12, 2021).

[1] By convention, transliterations are written in bold (Düwel 2004:123; Knirk 2002:635).