First and main author: Noorullah Shaikhnag – Noorullah.Shaikhnag@nwu.ac.za

Id orcid.org/ 0000-0002 1423 7696

Senior lecturer –Deputy Director, North-West University, Faculty of Education- Mafikeng campus

B Com (UDW-UKZN), BEd, MED, PhD (Educational Psychology, NWU).

Co-author: Thomas Buabeng Assan – Buabeng.Assan @nwu.ac.za

Emeritus Professor. Faculty of Education – Mafikeng.

Co-author: Professor Anna-Marie (AMF) Pelser – anna.pelser@hotmail.com

iD orcid.org/0000-0001-8401-3893

Research Professor, North-West University, Faculty of Economic and Financial Sciences- Entity Director – GIFT, Mafikeng Campus.

HED (Home Economics, PU for CHE), B Com (UNISA), B Com Hons (PU for CHE), M Com (Industrial Psychology, NWU), PhD (Education Management, NWU)

Corresponding author Prof A.M.F. Pelser – ampelser@hotmail.com

Co-author: Dr Shantha Naidoo – Shantha.Naidoo@nwu.ac.za

ID ORCID:https://orcid.org/0000-0001-8107-6493

North-West University, South Africa: Potchefstroom, North West, ZA

Lecturer: Life Orientation, Sub Area Leader: Edu-HRight (Bio-Psychosocial Perspectives)

MED (Learner Support), PhD (Educational Leadership and Management, UJ).

Abstract

This article is based on the investigation as to whether the decision to abolish physical punishment was viable and whether the abolishment had any impact on the teaching/learning process. A sample was drawn of 400 learners and 100 teachers from 20 high schools in an educational region of the North West Province of South Africa. The population was made of 40 schools, 1 200 learners and 300 educators. In contrast to the thrust of the theoretical investigation which revealed that the abolition of corporal punishment did dampen the teaching/learning domain, the empirical investigation, particularly the application of the chi-squared test, indicated that no positive relationship exists between the abolition of corporal punishment and the process of teaching-learning. The study, therefore, recommends that alternative forms of disciplinary measures are necessary to influence positive and sustainable teaching and learning practices, but not to totally eliminate the latter as its implementation can occasionally help to minimise disruptive behaviour.

Keywords: Abolition, Corporal punishment; Discipline; Disruptive behaviour, Learning and Teaching.

Introduction and Background

The present situation in South African schools seems to suggest that a lack of discipline and increase in violence among high school students has led to a continuation of unsuccessful learning and teaching, hence an increase in misconduct which affects the lives of both learners and teachers (Mthanti & Mncube, 2014). Discipline in a positive sense refers to learning, regulated scholarship, guidance and orderliness. Discipline may therefore qualify as an integral part of an effective educational endeavour in which parents and teachers give assistance to a learner seeking help (Stenhouse, 2015). On the other hand, violence can result in serious long-standing physical, emotional and psychological implications for both learners and teachers and these include reduced self-esteem, distress, risk of depression, suicide, reduced school attendance, diminished ability to learn and even school dropout (Unisa, 2012).

In view of this, it must be remembered that despite corporal punishment being abolished, schools remain places of learning and teaching. As such, they require certain basic regulations that govern, control and direct behaviour of learners and educators, thus control is imperative for effective learning and teaching (Lukman & Hamadi, 2014). Learners especially in the rural schools of South Africa are highly ill-disciplined, come to school under the influence of alcohol, display inappropriate sexual behaviour and are violent, learners also die at the hands of fellow learners, show total disrespect to teachers and murdering them in classrooms is unacceptable, (Sunday Tribune, 2009, Ramadwa, 2020). From the time learners became aware that corporal punishment had been outlawed, a state of unruliness prevailed. Many learners took advantage of this situation because they realised that no physical punishment will be meted out to them, students do not listen, carry dangerous weapons, drink alcohol and use drugs at school and do not have any respect whatsoever (Mahamba, 2019). With regard to the need for discipline, Gaustad (2012) suggests that the main goals of discipline are to ensure the safety of learners and teachers so that an environment conducive to learning can be created. This article even though rooted in the South African context, the findings should have a wider significance, not only within the Southern African regional context but should be of considerable importance particularly for the rest of Africa and the world in general. In the face of globalisation which is accelerated by Information Communication Technology (ICT), the results from this study are envisaged, could enhance world awareness on disciplinary issues among teenagers who are in or out of formal schooling. Thus principals should organise and hold school-based workshops on disciplinary measures.

Conceptual Framework

Corporal punishment in schools is defined as action with the aim of bringing about discipline which is physical in nature and meted out by educators or school administrators for some kind of disruptive behaviour (Schwartz, 2018). Physical

punishment is the use of physical force with the intention of causing pain to the child, but not injury, suffering or loss that serves as retribution and where unpleasant consequences follow socially unacceptable behaviour (Gershoff & Font, 2016). Corporal punishment is a kind of discipline that entails direct infliction of pain on the physical body. However, it is not restricted to this, but can be taken beyond the physical to emotional and psychological domains such as verbal abuse, and depriving the learner of basic needs like food and the use of the bathroom (Leigh, Chenhall & Saunders, 2009; Invocavity, 2014). The idea behind this practice is to control students’ behaviour causing pain which is meted out by a teacher, administered for an offence that the student has committed.

Moreover, this type of physical punishment can also be seen as a disciplinary measure that uses physical force with the intention to provide an immediate response to disruptive behaviour which forces the learner to be immediately back in the classroom learning (Goodman, 2020). Punishment at schools includes expulsion, suspension, physical pain, pinching, punching, smacking and kicking (Akhtar & Awan, 2018). In view of this, teachers face a great deal of difficulty in an attempt to create a stable learning environment. Teachers are continually tested by learners to such an extent that issues of discipline are frequently perceived as a direct threat to the learning-teaching environment (Furedi, 2016). Opponents of corporal punishment however indicate that it is tantamount to violence and abuse and that alternate measures are more effective (Nakpodia, 2014). Thus, the impact of violence in schools often leads to serious social and economic consequences which in turn affects learning and teaching (Case, 2017; Mthanti & MnCube, 2014).

Disruptive behaviour continues to be the most consistently discussed problem in South African Schools as well as in other parts of the world. Disruptive behaviour is problematic and interaction between teacher and learners is extremely important so that learning activity can take place in a dignified manner (Marais & Meier, 2010, Fakhruddin, 2018) while the South African Council of Educators (2011) as well as Serame, Oosthuizen, Wolhuter and Zulu (2013) indicate that violence is a serious concern in both primary and secondary schools in South Africa and reported problems with bullying, fighting and physical violence among learners, as well as intimidation of educators by learners and vice versa, has led to serious implications on the learning-teaching process and such interruptions negatively affect learners in the classroom (Daniels, 2018). According to the Department of Education (2014) in some cases, the results of disruptive behaviour such as bullying may lead to a learner experiencing social, mental or emotional health issues which in turn prevents learners from feeling happy at school and achieving a satisfactory academic record (Ndebele & Msiza, 2014). This is corroborated by Fakhruddin (2018) who reported that disruptive behaviour does not fulfil what is expected to be done inside the classroom and during the academic activity which eventually leads to high rates of dropout and absenteeism among students who experience disruptive behaviour. Discipline thus is important for the safety of all learners and their educational wellbeing Masitsa 2008, Sharma, 2020). In a study conducted by Gwando (2017) it was found that many students believed that corporal punishment helped them to reach their academic goals. The introduction of the Schools Act 84 of 1996 did not help the discipline process much as corporal punishment was done away with. Despite the abolition of corporal punishment, classroom discipline is extremely important in maintaining a learner-teacher relationship as well as improving teacher effectiveness and enhancing learner results (Lopez & Oliveira, 2017).

Corporal punishment is controversial with some psychologists arguing in its favour and others calling for its abolition (Mwamwenda, 2008). Research in South Africa shows that schools continue to administer corporal punishment to curtail misconduct among learners and the majority of the teachers surveyed as well as some psychologists believe that corporal punishment was justified in the sense that it gives teachers control to ensure that violence among learners is curtailed and also it can improve child behaviour (Bailey, Robinson & Coore-Desai, 2014, Gershoff, Goodman, Miller-Perrin, Holden, Jackson & Kazdin, 2018). Tozer (2012) on the other hand believes that the use of violence is an issue of power as teachers believe that violence can be used to control those weaker than others. This is done in order to control indiscipline in schools, but at times teachers act irrationally causing more harm than gain, hence it is argued that corporal punishment negatively affects relationships and often creates resentment and hostility, which have been associated with school dropout and vandalism (Kambuga, Manyengo & Mbalamula, 2018). Corporal punishment is thus seen as being ineffective which ultimately leads to detrimental outcomes for the learner which has never produced good results, it is like sweeping dirt under the carpet, the problem is only covered up not solved, its disadvantages far outweigh the merits, hence it should not be used as a means to improve the quality of learning and teaching (Frankie, 2020, Golden, 2018).

Corporal punishment in the South African context

In South Africa, corporal punishment has been banned by Section 10 of the Schools Act of 1996 and has made the administration of corporal punishment a criminal offence in South African schools. Therefore, educators need to formulate strategies that take account of learners’ rights and protection (Maphosa & Shumba, 2010). Many South African educators have difficulty finding an alternative to this traditional method of punishment and it is argued that corporal punishment persists because parents use it at home and support its use at school, parents agree on the use of corporal punishment in schools since it yielded positive results in respect of discipline (Bhana, 2012, Gambanga, 2015). Corporal punishment belongs to the traditional classroom where it was the main form of punishment. It also passed down the ages in the history of schooling until it was challenged by educational theorists of the progressive era (Maphumulo & Vakalisa, 2008). Educators should therefore find Alternatives to corporal punishment (ATCP) which is a disciplinary measure that stresses effective communication, respect and positive educational relations between teachers and learners (Moyo, Khewu & Bayaga, 2014).

Unfortunately, this was not to be as research has shown that since the inception of ATCP in 2000, misconduct in schools continued to grow (Maphosa & Shumba, 2010) and Marais and Meier (2010). It was further stressed by Lopes and Oliveira (2017) that the outlawing of physical punishment led to the teaching profession becoming stressful and challenging. Teachers were demotivated, consequently, the learners were subject to poor quality teaching. Similarly, Shaikhnag and Assan (2014) supported by Lopes and Oliveira (2017) contend that the abolishing of corporal punishment in schools had far-reaching implications for the teaching fraternity, many educators were incapacitated and were unable to deal with learner misbehaviour adequately. Moreover, physical punishment often leads to short-term compliance and therefore appears to be effective, but actually has negative short-term and long-term effects (Ancer, 2013, Mthanti & Mncube, 2014). Studies have established a strong relationship between corporal punishment and the development of aggressive behaviour by learners, hence corporal punishment has a tendency to develop aggressive hostility instead of self-discipline. For many learners, especially boys, it leads to feelings of revenge, anti-social aggressiveness and a high rate of vandalism (Gershoff & Gregan-Kaylor, 2016). This will ultimately impact students’ academic achievement and long term well-being (Zolotor & Puzia, 2012). To avoid this, Akhtar and Awan (2018) contend that teachers ought to take cognisance of the negative impact of corporal punishment by engaging learners in seminars, workshops, interactive discussions and encouraging programmes so that corporal punishment can be stopped

The present situation in South African schools demonstrates that a lack of discipline and self-discipline among high school learners has led to a continuation of unsuccessful learning and teaching, (Makhasane & Chikoko, 2016, Mthandi & Mncube, 2014). As it is unethical to physically punish learners according to the Schools Act, no 10, the then Minister of Education, designed a comprehensive document entitled ‘Alternatives to Corporal Punishment’. Research conducted by the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry (2020) reveals that corporal punishment is less effective than other methods of behaviour in schools.

Praising and discussing value systems, providing motivational measures and creating a competitive environment as well as positive role models play an intricate part in developing respect for teachers (Awan, 2015). This also assists in maintaining social justice posits (Veriava & Power, 2017). Disciplinary measures to be taken in South African schools are clearly outlined in different levels and the focus should be on ensuring a safe and established schooling environment for learners. Possible options are reward charts, merit and demerit systems, withholding privileges, time out, detention and cleaning the schoolyard, (Maphosa & Shumba, 2010, Ebrahim, 2017).

Thus, the permissive style of discipline which has an optimistic view of human nature and believes that if learners are left alone, they will make good decisions and behave in a favourable way that might be best suited to the South Africa scenario. In order to achieve this, leaders must be able to motivate educators to strengthen their confidence and to stimulate their creativity which ultimately will lead to a comfortable environment (Lumadi, 2017, Zabel & Zabel, 2006). This article has pointed out that abolishment of corporal punishment in South Africa has contributed to the need for alternative remedies to control and promote sustainable effective teaching and learning in schools.

Problem Statement

The problem of discipline and punishment in schools has been part of the education profession for a long time now, and there seems to be no solution. Debate based on religious, social and cultural values suggests that it is essential to punish children, physically, because it helps to bring about the values of society, good conduct and discipline in them (Lukman & Ali, 2016). Abolition of corporal punishment is tantamount to loosening the teachers’ grip on the learners. The inference here is that, if used judiciously, this type of punishment brings about an immediate decrease in bad behaviour, produces respect for authority, obedience and self-discipline (Ogando Portela & Pells, 2015, Seidal & Alexa, 2018). It can be argued, on the other hand, that corporal punishment does not result in long-term behavioural change and tends to be counterproductive since a learner could develop impaired cognitive development (Poulsen, 2015). Also, no compelling evidence exists to support the claim that physical strikes can improve a child’s behaviour or mental health, to the contrary it can retard learner progress and even lead to death and permanent disability (Bassam, Marianne, Rabba & Gerbaka, 2018; Russo, 2015).

In a study conducted by Govender and Sookrajh (2015) it was said that corporal punishment is still used on a large scale in some classrooms. As the learning-teaching process involves the transfer of knowledge through teachers, it is imperative that they maintain authority which is a routine feature of the teaching-learning process (Chafi, Elkhouzi & Ouchouid, 2016).

This article purports to shed light on and provide insight into the challenges experienced by schools around three regions in the Area Offices of the North West Province of South Africa concerning learner conduct as well as the effects of banning corporal punishment on the learning/teaching environment. In order to discover such effects, the null hypothesis tested was “there is a significant relationship between the abolition of corporal punishment and nature of the teaching-learning environment”. Variables that are linked to the teaching-learning process were identified and used for the Likert scale. These variables serve as factors influencing the teaching-learning aftermath of the abolishment of corporal punishment.

Research Paradigm, Design and Methodology

The research was contextualised by the post-positivist paradigm based on the following assumptions (Creswell, 2016): Firstly, all knowledge is conjectural; therefore absolute truth cannot be established. Secondly, research is a process of making claims, thereafter refining them or abandoning them to accommodate other claims that deserve more attention. Finally, post-positivism is not a form of relativism and can therefore retain the idea of objective truth. The data was collected using the quantitative method and was underpinned by a post-positivistic research theory whose assumptions represent the traditional form of research.

Research Design and Approach

A survey design was used to describe and explain the status of phenomena, to trace change and to draw comparisons. A survey in contrast to survey research is a data collection technique through which a researcher can produce survey research. Thus implicit in the notion of the survey is the idea that research should have a wide range – a breath-taking view, i.e. a panoramic view and ‘taking it all in’. Similar to this research, surveys relate to the present state of affairs and involve an attempt to provide a view of how things are at a specific time at which data is collected (Leedy & Ormrod, 2012; Maree, 2012, Showkat, 2017).

These hold true more for quantitative research than the qualitative approach (Creswell, 2016). Thus it became apparent that using the quantitative method in analysing data would be best suited for the study since this approach involves collecting numerical data which are objective and not influenced in any way by the researchers’ prejudice (Eyisi, 2016; Streefkerk, 2020).

Population and Sampling

The target population included high schools in one educational region of the North West Province (n=20) and it was selected with the assistance of the Area Project Officers regional managers. The findings of the study are therefore valid for schools in this region only.

Simple random sampling was used and the sample size included twenty schools (n=20). In total, 500 questionnaires were distributed to 400 students and 100 were handed out to teachers. The response rate was 95%.

Table 1: Population and Sample

|

Population |

Sample |

||||||||

|

Schools in one region of NW |

Number of schools |

Learners |

Educators |

Number of schools selected |

Learners |

Educators |

|||

|

|

40 |

1200 |

300 |

20 |

400 |

100 |

|||

Data Collection Instrument

Based on the evidence at hand, it was inferred that the best way of gathering information directly from respondents would be by means of a scheduled structured questionnaire. This method is based on a set of questions with fixed wording and indicators of how to answer each question, thus a structured (closed-ended) questionnaire using the four (4)-point Likert scale was used since it is characterised by choices between alternative responses that are given (Strongly agree, Agree, Disagree and Strongly disagree). A self-constructed questionnaire with twelve items was used. (Burns & Bush 2014, Kumar, 2016). The questionnaire had only one section and the wording was such that it could easily elicit appropriate reactions from the respondents. The instrument was pilot tested for standardisation. With this type of questionnaire, data can be enlarged and classified more easily and the number of possible responses is limited.

The researcher distributed the questionnaires personally. This had the advantage that the purpose of the study could be explained clearly before the respondents attempted to respond to the questions. Most of the completed questionnaires were collected almost immediately, but some had to be collected at a later stage due to students writing tests.

Data Processing

Computer-aided statistical analysis was employed in the form of calculating frequencies, percentages, means and chi-squares through the use of meta-analysis (Guerrero, 2019; Kaplan, 2012). The usual procedure is that if the P-value is less than the significant level, usually 0.05, the hypothesis is rejected (Prabakharan, 2016).

Table 2: Cronbach’s Alpha

|

Variable |

N |

Mean |

STD Dev |

Cronbach’s |

Comment |

|

School 20 |

Variable |

3.75 |

1.27 |

0.726 |

Acceptable & consistent |

Ethical Considerations

Ethical guidelines were followed, which included guaranteeing confidentiality and anonymity of the participants. Permission to carry out this investigation was granted by the Provincial Department of Education and further consent was given by the headmasters as well as the school governing bodies to conduct research at their schools.

Findings

Abolishing of Corporal Punishment and its Effect on Teaching-Learning Practices

Table 3 below presents the responses to the questionnaire relating to the relationship between the abolishment of corporal punishment and the teaching-learning process. Table 3 and Figure 1 below present the findings.

Table 3: Candidates (including educators) responses to questionnaire on corporal punishment and the teaching/learning process

|

STATEMENTS |

STRONGLY AGREE |

AGREE |

DISAGREE |

STRONGLY DISAGREE |

TOTAL |

|

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

||

|

Since the banning of physical punishment: Learners attend school regularly. |

70 (14.2%) |

234 (47.6%) |

124 (25.2%) |

64 (12.6%) |

492 (100) |

|

Learners arrive at school on time daily which allows teaching to take place smoothly. |

34 (6.9%) |

155 (31.4%) |

207 (42.0%) |

97 (19.7%) |

493 (100) |

|

Students are on time after school break, thus teaching goes on normally. |

42 (8.6%) |

106 (21.7%) |

271 (55.4%) |

70 (14.3%) |

489 (100) |

|

Learners stay at school the whole day doing their work. |

78 (15.9%) |

168 (34.3%) |

186 (38.0%) |

55 (11.8%) |

490 (100) |

|

Learners adhere to the dress code, this motivates teachers, |

87 (17.7%) |

258 (52.2%) |

113 (23.0%) |

34 (6.9%) |

492 (100) |

|

Learners always wear school uniforms which enhances the teaching process. |

131 (26.6%) |

274 (55.7%) |

66 (13.4%) |

21 (4.3%) |

492 (100) |

|

Learners have the necessary books, hence teachers find it easy to teach. |

140 (28.4%) |

254 (51.5%) |

79 (21.3%) |

20 (4.1%) |

493 (100) |

|

Learners have sufficient stationery making teaching pleasant |

120 (24.4%) |

246 (50%) |

105 (21.3%) |

21 (4.3%) |

492 (100) |

|

Students obey/do not obey school rules which could motivate/demotivate educators |

49 (10%) |

173 (35.2%) |

183 (37.3%) |

86 (17.5%) |

491 (100) |

|

Learner/Teacher relationship is very good and this leads to better teaching |

49 (10.0%) |

213 (43.5%) |

177 (36.1%) |

51 (10.4%) |

490 (100) |

|

Learners always do their homework, despite CP being outlawed. |

47 (9.6%) |

168 (34.1%) |

232(47.2%) |

45(9.1%) |

492(100) |

|

Learners take pride in their work, despite CP being banned. |

46 (9.3%) |

232 (47.0%) |

187 (37.9%) |

29 (5.9%) |

494 (100) |

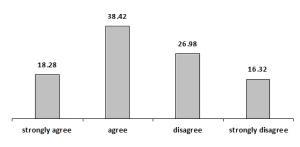

Figure 1, the bar chart, indicates that the majority of participants agreed that the abolition of corporal punishment does have a bearing on teaching and learning.

Figure 1 Teacher and learner responses with regard to corporal punishment and its effect on teaching and learning

Table 3 and Figure 1 are based on elements of students’ behaviours in the aftermath of the abolishment of corporal punishment. The responses in Table 3 indicate that the majority (61.8%) of the respondents attend school regularly, while 61.7 % disagreed that learners come to school on regular basis A large percentage of respondents 69.7% disagreed that learners are timeous after the break. 50.2% agreed that learners stayed at school the whole day doing their work. The majority of the respondents 69.9% asserted that learners adhere to the dress code which enhances teaching and 82, 3 % believed that students always wear school uniforms which makes the teaching-learning environment pleasant. The majority of respondents 79.9% agreed that learners have books and 74.4% indicated that learners had stationery, both of which influence the teaching-learning process. Only 45.2% agreed that learners obey school rules and regulations. The learner-teacher relationship is very good claimed 53.5% of the respondents, but 56.7% disagreed that learners do their homework regularly. The majority of the respondents 56.3% accepted the fact that learners take pride in their work despite corporal punishment being outlawed. On the whole, it can be deduced from the responses on these variables/elements of students’ behaviour after the abolishment of corporal punishment generally show that not many changes have been recorded which influence the teaching and learning process.

Relationship between Abolishing of Corporal Punishment and the Learning-Teaching Process

Based on the findings of the study, it is evident that in spite of corporal punishment being banned, there is a positive attitude towards the learning-teaching domain. However, the chi-squared test applied to the findings (Table 4) confirms that no significant relationship exists between the abolition of corporal punishment and the learning-teaching process. Consequently, there was no need to reject the null hypothesis; this suggests that there was no significant relationship between the abolition of corporal punishment and their behaviour elements/variables (positive attitudes) shown by learners thereafter such as attendance staying at school to do their work, dress code, having sufficient books, stationery etcetera. (Table 3).

Although the hypothesis states that the abolition of physical punishment has an effect on the learning-teaching environment, the chi-squared test applied to the data indicated that no significant relationship existed between the abolition of corporal punishment and the learning-teaching process, hence the failure to reject the null hypothesis. As the Pearson chi-square (P-value) values were 0.308 > 0.05 (significant point) (Table 4), the null hypothesis could not be rejected. Acceptance of the null hypothesis implied that the abolition of corporal punishment did not play a major role in the learning/teaching environment.

Table 4: Chi-squared test

|

Value |

Df |

Asymp sig 2 sided |

Exact sig 2 sided |

Exact sig 1 sided |

|

|

Person chi-squared |

1039a |

1 |

.308 |

||

|

Continuity Correction b |

.230 |

1 |

.631 |

||

|

Likelihood ratio |

1.108 |

1 |

.292 |

||

|

Fisher’s exact test |

.596 |

.324 |

|||

|

Linear by linear association |

.982 |

1 |

.322 |

||

|

N of valid cases |

18 |

Notes. a 2 (50%) have an expected count of less than 5. The minimum expected count is 1.94 b Computed only for a 2×2 table

Discussion

Generally speaking, the theory, as expounded above in the conceptual-theoretical framework, seems to suggest that the learner/teacher relationship might have deteriorated since the abolition of corporal punishment in schools. This was corroborated by Masitsa’s study (2008,) in which it was found that learners were not sufficiently disciplined since the abolition of corporal punishment. Learners were guilty of stealing other learners’ property, vandalizing school property, fighting amongst themselves and also stealing school property. This is further corroborated by Nakpodia (2014) suggesting that there are alleged cases of teachers being threatened by learners which makes it difficult to carry out their responsibilities. Teachers are subject to extreme difficulty in bringing about a stable learning environment. Teachers are also frequently tested by learners, making it virtually impossible to exercise discipline, teachers are helpless as they spend much time dealing with student misconduct in an attempt to stabilise and improve the learning-teaching environment (Furedi, 2016, Semali & Vumilia, 2016). Based on the conceptual framework and the literature review the hypothesis formulated was: “there is a significant relationship between the abolition of corporal punishment and nature of the teaching-learning environment” The empirical data in the study reported here and cross-tabulated, indicated a rejection of the hypothesis and established that no significant relationship was found between the abolition of corporal punishment in schools and the nature of the learning-teaching process.

Recommendations

In the light of the findings and empirical evidence, it is suggested that teachers consider further enhancing the effectiveness of classroom teaching and learning process by administering alternate ways of bringing about discipline. Principals should strengthen school-based workshops on learner behaviours and alternative disciplinary measures whereby the manual “alternatives to corporal punishment” should be formulated, discussed and implemented by all teachers. Such workshops should receive Continuous Professional Teacher Development (CPTD) points. Among other things which should receive attention in the manual include: focus on maintaining a safe and dignified schooling environment for educators as well as learners, reward charts, merit and demerit systems, taking away privileges, time outs, detention where learners can do school work and picking up litter. Manual should also include discussions and engagement that allow learners to learn insight into their misdemeanours and unacceptable practices as well as other barriers to effective teaching and learning.

Conclusion

The chi-squared test applied to the analysed data confirmed that no real connection existed between the abolition of corporal punishment and effective teaching and learning practices. This is understandable in view of the fact that literature studies, worldwide have linked corporal punishment to increases in aggression, more disruptive behaviour in classrooms, vandalism, lower academic achievement, poor attention span, school phobia, depression and even retaliation against teachers.

Note

-

Copy of questionnaire is available from the authors.

References

Akhtar, S.I. & Awan, A.G. 2018. The impact of corporal punishment on students’ performance in public schools. Global Journal of Management, Social Sciences and Humanities, 4(6):606-621.

American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2020. Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry 59(1).

Ancer, J. 2013. Corporal punishments’ effects linger forever. Sunday Times, 9 Jun 2013.

Awan, A.G. 2015. “Brazils Innovative Anti-Poverty and Inequality Model. American Journal of Trade and Policy, 11(3):7-12.

Bailey, C., Robinson, T. & Coore-Desai, C. 2014. Corporal Punishment in the Caribbean: Attitudes and Practices. Social and Economic Studies, 63(3&4):207:233.

Bhana, D. 2012 Girls are not free – in and out of the South African school.

International Journal of Education Development, 32:352-358.

Bassam, E., Marianne, T., Rabba, L. & Gerbaka, B. 2018. Corporal punishment of children: discipline or abuse? Libyan Journal of Medicine, 13(1):1485456

Burns, A.C. & Bush, RF. 2015. Marketing research Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson edition.

Case, H. 2017. Online – Long-term effects of physical punishment on a child. https://www.livestrong.com/article/492069-behavioral-side-effects-of-hgh. Date of access: 15 Dec 2019.

Chafi, E., Elkhouzai, E.L. & Ouchouid, J. 2016. Teacher excessive Pedagogical Authority in Moroccan Primary Classrooms. American Journal of Educational Research, 4(1):134-146

Chauke P. 2015. Corporal punishment instigates school violence. http://citizen.co.za/145486/corporal-punishment-instigates-violence. Date of access: 14 Mar 2019.

Creswell, J.W. 2016. Research Design, Qualitative, Quantitative and Mixed methods approach. London: Sage.

Daniel, A. 2018. Pupil absence in schools in England. http://www.gov.uk/govrnment/publications. Date of access: 14 Jun 2019.

Ebrahim, S. 2017. Discipline in schools: What the law says you can and can’t do. https://mg.co.za/article/2017-11-09-discipline-in-schools-what-the-law-says–you-can-cant-do/ Date of access: 17 Jun 2020.

Eyisi, D. 2016. The usefulness of qualitative and quantitative approaches and methods in researching problem-solving ability in science education curriculum. Journal of Education Practice 7(15):94-94.

Fakhruddin, M.Z. 2018. Managing disruptive behaviour in the class. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/330039674. Date of access: 16 May 2020.

Frankie, U.K. 2020. Advantages and disadvantages of Corporal-Punishment. https://hostbeg.com/advantages-disadvantages-corporal-punishment. Date of access: 14 Mar 2020.

Furedi, F. 2016. Parents are undermining teachers’ authority and it’s causing havoc in schools. International Business Times.

Gambanga, J. 2015. Is corporal punishment really bad for juveniles? http://www.zbc.co.zw/news-categories/opinion/51619-is-corporal-punishment-really-bad-for-juveniles. Date of access: 20 Dec 2019.

Gaustad, J. 2012. School Discipline. http://ccbingji.com/cacheaspx?q=School-Discipline. Date of access: 19 Feb 2012.

Gershoff, E.T., Goodman, G.S., Miller-Perrin, C.L., Holden, G.W., Jackson, Y. & Kazdin, A.E. 2018. The strength of the causal evidence against physical punishment of children and its implications for parents, psychologists and policymakers. American Psychologist, 73(5):626-627

Gershoff, T. & Gregan-Kaylor, A. 2016. The effect of corporal punishment on anti-social behaviour in children. National Association of Social workers, 28(3):153-162.

Gershoff, T.& Font, S. 2016. Corporal Punishment in U.S. Public schools: Prevalence, Disparities in Use, and Status in State and Federal Policy. https//www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5766237. Date of access: 19 Dec 2019.

Golden, B. 2018. Further support against physical punishment for discipline. http://www.psychologytoday.com/us/blog/overcoming-destructive-anger/201807/further-support-against-physical-punishment-discipline Date of access: 19 May 2020.

Goodman, P. 2020 Arguments for and against the use of corporal punishment in schools. https://soapboxie.com/social-issues/Should-corporal-punishment-in-schools-be-allowed-Arguments-for-and-against. Date of access: 17 Mar 2020.

Govender, S. & Sookrajh, R. 2015. ‘Being hit was normal’ Teachers’ un(changing) perceptions of discipline and corporal punishment. South African Journal of Education, 34(2):1.

Grayson, J. 2008. Corporal Punishment in schools. Virginia Child Protection Newsletter, 76:12-16.

Gundersen, S. & Mckay, M. 2019. Reward or Punishment? An examination of the relationship between teacher and parent and test scores in the Gambia. International Journal of Education Development, 68(1):20-34.

Guerrero, H. 2019. Analysis of Quantitative Data: Modelling and Simulation. https//www.scribbr.com/methodology/qualitative/quantitative-research. Date of access: 19 Mar 2020.

Gwando, R.H. 2017. Pupils’ perceptions on corporal punishment in enhancing discipline in primary schools in Tanzania survey study of primary schools at Kawe Ward in Kinondoni. Published Master’s thesis. The Open University of Tanzania.

Invocavity, J. 2014. The effects of corporal punishment on discipline among students in Arusha secondary schools. Masters thesis, University of Tanzania. http://repository.out.ac.tz/582/1/Dissertation-JOSEPHINE-12-11-2014-B.pdf. Date of access: 14 Mar 2016.

Kambuga, Y.M., Manyengo, P.R. & Moalamula, Y.S. 2018. Corporal punishment a strategic reprimand used by teachers to curb students’ misbehaviours in secondary schools: Tanzanian Case. International Journal of Education and Research. 2(19):268-271.

Kaplan, D. 2012. The Sage handbook on qualitative methodology for the social sciences. London: Sage Publications.

Khubeka, A. 2018. These are the alternatives to corporal punishment. https://www.iol.co.za/dailynews/these-are-the-alternatives-to-corporal-punishment-17522863. Date of access: 18 Jan 2020.

Kumar, R. 2016. Research Methodology. A step-by-step guide for beginners. USA: Sage Publication

Leedy, P.D. & Ormrod, J.E. 2012. Practical Research. Upper Saddle River: Pearson.

Leigh, K.E., Chenhall, E. & Saunders, C. 2009. Linking Practice to the Classroom: Teaching Performance Analysis. Paper presented at the Academy of Human Resource Development, Washington, 21-22 May 2009.

Lessing, A.C. & Dreyer, J. 2007. Every teacher’s dream: discipline is no longer a problem in South African Schools. Pretoria: Van Schaik Publishers.

Lopes, J. & Oliveira, C. 2017. Classroom discipline: Theory and practice. In J.P. Bakken (ed). Classrooms: Academic content and behavior strategy instruction for students with and without disabilities. New York: Nova Science Publishers.

Lukman, A.A. & Ali, A.H. 2106. Disciplinary measures in Nigerian senior secondary schools: Issues and prospects. Journal of Research & Method in Education, 4(3):11-17.

Lumadi, R.I. 2017. Ensuring educational leadership in the creation and leadership of schools. KOERS 82:(3).

Mahamba, C, 2019. Can return of corporal punishment bring discipline in schools? https://www.iol.co.za/the-star/news/can-return-of-corporal-punishment-bring-discipline-in-schools-21556881. Date of access: 26 Nov 2019.

Makhasane, D. & Chikoko, V. 2016. Corporal punishment contestations, paradoxes and implications for school leadership: A case study of two South African high schools. South African Journal of Education, 36(4):1-5.

Maphosa, C. & Shumba, A. 2010. Educators’ Disciplinary Capabilities after the Banning of corporal punishment in South African Schools. South African Journal of Education, 30(3):387-399.

Maphumulo, N.C. & Vakalisa, N.C.G. 2008. Classroom Management. In Jacobs, M., Vakalisa, M. & Gawe, N. (eds). Teaching–learning dynamics – a participating approach. Johannesburg: Heinemann.

Marais, P. & Maier, C. 2010. Disruptive behaviour in the foundation phase schooling. South African Journal of Education, 30(1):41-57.

Maree, K. 2012. First Steps in Research. Pretoria: Van Schaik Publishers.

Masitsa, G. 2008. Discipline and disciplinary measures in the Free State township schools: Unresolved problems. Acta Academica, 40(3):234-270.

Moyo, G. Khewu, P.D. & Bayaga, A. 2014. Disciplinary practices in schools and principles of alternatives to corporal punishment strategies. South African Journal of Education, 34(1):3-4.

Mthanti, B. & MnCube, V. 2014. The Social and Economic Impact of Corporal Punishment in South African Schools. Journal of Sociology Social Anthropology, 5(1):71-80.

Mwamwenda, T. 2008. Educational Psychology: An African Perspective. Umtata: Butterworths.

Ndebele, C. & Msiza, D. 2014. An analysis of the prevalence and efforts of bullying: Lesson for school principals. Studies of Tribes and Tribals, 12(1):113-124.

Nakpodia, E.D. 2014. Teachers’ disciplinary approaches to students’ discipline problems in Nigerian secondary schools. International NGO Journal, 5(6):144-151.

Ogando, S., Portella, M.J. & Pells, K. 2105. Corporal punishment in schools: longitudinal evidence from Ethiopia, India, Peru and Vietnam. https://www.unicef.org/ecuador/CORPORAL-PUMISHMENT-IDP2/finalrev.pdf. Date of access: 16 Nov 2019.

Poulsen, A. 2015. The Long term impact of corporal punishment. http://www.smh.com.au/comment/the-long-term-impact-of-corporal-punishment. Date of access: 20 Mar 2016.

Prabakharan, S. 2016. Chi-Squared test. R-blogges.com/chi squared test. Date of access: Dec 2018.

Protogeru, C. & Flisher, A. 2012. Bullying in schools. Crime, violence and injury in South Africa. 21st century solutions for child safety. Tygerberg: MRC.

Ramadwa, M. 2018. Lack of discipline in schools concerning, but teachers not totally disempowered. https://www.news24.com/MyNews24/lack-of-discipline-in-schools-concerning-but-teachers-not-totally-disempowered-20180918. Date of access: 15 May 2020.

Republic of South Africa. 1996. Schools ACT, no. 84 of 1996. Pretoria: Government Printer.

Russo, J. 2015. Child Discipline and Corporal Punishment. http://www.livestrong.com/article/74424-child-discipline-corporal-punishment/. Date of access: 18 Apr 2015.

Schwartz, P., Semali, L.M. & Vumelia, P.L. 2016. Challenges facing teachers’ attempts to enhance learners’ discipline in Tanzania’s Secondary Schools. World Journal of Education, 6(1):25-31.

Shaikhnag, N. & Assan, T. 2015. The effects of Abolishing Corporal Punishment on Learner Behaviour in South African High Schools. Mediterranean Journal of Social Sciences, 5(7):435-440.

Seidal, M. & Alexa, J. 2018. The Advantages of Corporal Punishment. https://legalbeagle.com/8211462-advantages-corporal-punishment.html Date of access: 02 Feb 2020.

Sharma, V. 2020. Importance of discipline in school life. http://www.kleintsolutech.com/importance-of-discipline-in-school-life. Date of access: 26 Nov 2019.

Showkat, N. 2017. Quantitative methods: Survey. researchgate.net/publication/318959206_Quantitative_Methods_Survey. Date of access: 18 Jun 2019.

Stenhouse, L. 2015. Discipline in Schools: A Symposium. Oxford: Pergamsen Press.

Streefkerk, R. 2020. Qualitative vs quantitative research.

https://www.scribbr.com/methodology/qualitative-quantitative-research. Date of access 5 September 2019.

South African Council of Educators. 2011. School-based Violence Report: An overview of School-based violence in South Africa. Centurion: SACE.

Sunday Tribune. 2009. Violence in our schools, 14 May.

Tozer, J. 2012. ‘We are letting the Pupils Take Over’: Teacher cleared over confrontation with girl, 13, warns of anarchy threat. Mail Online, http://www.dailymail.co.uk/news/article-1307201. Date of access: 14 Dec 2013.

Unisa. 2012. The New Age Newspaper, 8 March. http://www.thenewage.co.za. Date of access: 23 Mar 2012.

Veriava, F. & Power, T. 2017. Corporal Punishment. https://eelawcentre.org.za/corporal-punishment-authored-faranaaz-veriava-section-27-tina-power-legal-resources-centre/. Date of access: 19 Dec 2019.

Wilson, E. 2009. School-based research: A guide for education students. London: Sage.

Zabel, R.H. & Zabel, M.K. 2006. Classroom Management in context (6th ed). Boston: Houghton Mifflin.

Zoloto, A.J. & Puzia, M.E. 2012. Bans against Corporal Punishment: A systematic review of the laws, changes in attitudes and behaviours. Child abuse Review, 19:229-247.